The Climate Opportunity of Clean Energy Portfolios

Avoiding most new natural gas plants in the United States can save money and curb carbon emissions to support international climate targets

As global climate leaders gather in New York City this week, the scope and scale of the challenge in meeting international climate targets has never been clearer. On the other hand, neither has there ever before been such a confluence of technology, business-led innovation, and market-aligned policy that, together, can help us make near-term, material progress toward the global challenge of our time.

For a clear and salient example, consider the role of natural gas in the US power sector. Long viewed by the gas and electricity industries as a “bridge fuel” away from coal that can enable a clean energy future, there is now fast-building evidence that new gas capacity, itself, is the primary driver of increased carbon emissions on the grid.

But today, advances in renewables and storage technology and emerging best practices in grid planning mean that there are now cost-effective and reliable opportunities to avoid locking in costs and emissions associated with new gas plant investment. We have a limited time to take advantage of these economic opportunities and avoid the stranded costs, committed emissions, or even both, that would threaten the otherwise rapidly accelerating clean energy transition.

The Need for a Low-Carbon Grid to Enable Economy-Wide Decarbonization

In order to prevent the most catastrophic impacts of climate change, there is a growing consensus that the United States must reduce its emissions by at least 80 percent of 2005 levels by 2050. There is also an emerging recognition that the most cost-effective way to make near-term progress toward this goal is to rapidly transition from the direct use of fossil fuels in vehicles and buildings, and instead use zero-carbon sources of electricity to provide these energy services.

Analytically rigorous studies from US geographies as diverse as the Northwest, Colorado, and the Northeast all show the important role of transport and heating electrification coupled with a very low-carbon grid in cost-effectively reducing emissions on an economy-wide basis. And while greenhouse gas emissions from the US electricity sector today account for only 28 percent of total emissions, the grid is a near-term target for decarbonization because it will need to grow in energy delivered while shrinking its emissions to support economy-wide emissions targets.

The Shrinking Role for Gas as a Bridge Fuel

The US electricity sector’s emissions declined significantly in the decade between 2008 and 2017, in large part driven by the declining share of coal-fired generation replaced by lower-cost and lower-emissions gas-fired generation. This has given rise to the notion of gas being a “bridge fuel” to a lower-carbon grid.

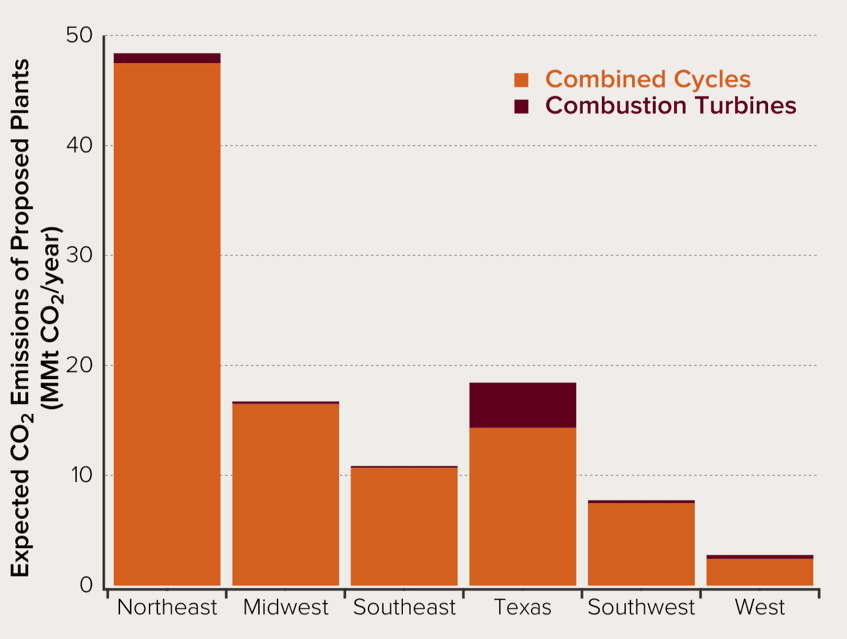

But in 2018, grid emissions rose as gas generation increased to meet weather- and growth-related demand. This trend is set to continue: in the United States, developers have proposed investing $70 billion in new gas plants through 2025, with an associated increase of 100 million tons of CO2 emissions each year (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Expected annual CO2 emissions from proposed new gas-fired power plants

The grid’s rising emissions in 2018 illustrate the limits of coal-to-gas switching as an emissions reduction strategy. At the same time, steep cost declines in renewables and storage over the last decade have also limited the economic argument for new gas plant investment. New research from Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI) shows that it is possible to save both money and carbon by avoiding most gas plants currently proposed for construction, and investing instead in “clean energy portfolios”—combinations of zero-emissions technologies that, together, can provide the same energy and reliability services to the grid.

Recent market experience is consistent with research findings that clean energy portfolios are preferable to most new gas investment. Leading utilities across the US are stepping away from investment in new gas plants, instead prioritizing investment in wind, solar, batteries, demand flexibility, and energy efficiency, that together can offer equivalent reliability, lower costs, and lower emissions. Where new gas plants are being pursued most economically, they are increasingly smaller, more flexible, and designed to operate more as a balancing resource to accommodate wind, solar, and load variability, rather than as an “always-on” replacement for existing fossil capacity. As a result, these “peaker” plants have a much lower emissions impact.

Preserving the Carbon Budget While Reducing Customer Costs

As noted above, proposals to invest in new gas-fired capacity through 2025 would result in 100 million tons per year of CO2 emissions if these plants are operated at typical capacity factors. Upstream emissions from methane leakage during gas extraction and pipeline transportation would increase CO2-equivalent (CO2e) greenhouse gas emissions approximately 85 percent, for a total of 185 million tons of CO2e emissions.

These emissions represent a significant share of the US carbon “budget” under a wide range of decarbonization scenarios. In 2005, the US emitted over 7.3 billion metric tons of CO2-equivalent greenhouse gases. An indicative 80 percent reduction goal would imply a budget of just 1.4 billion tons of annual CO2e emissions across the US economy—a level of emissions likely too high to limit warming to 1.5°C. In other words, new gas power plants proposed for construction in the next five years alone would account for at least 13 percent, and likely much more, of the entire economy’s annual carbon budget.

Instead of locking in these emissions for decades to come, there is instead an opportunity today to economically prioritize clean energy portfolios at a cost savings to consumers. RMI’s research shows how avoiding construction of 90 percent of proposed gas plants would save US electricity customers over $29 billion on a net present value basis.

We Cannot Afford Not to Act

Climate change mitigation has long been slowed by economic arguments that state, in effect, we cannot afford to take action that will materially reduce emissions. Today, that is definitively not the case; in fact, we now have a clear opportunity to reduce electricity bills while also avoiding future carbon emissions that would slow progress toward climate targets. Opportunities to save money and carbon have never before been so well-aligned, but there is no time to lose.