Changing the Climate Forecast in 2024 — Five Ways Power Sectors Worldwide Can Drive Down Emissions

There is no one-size-fits-all method to clean up global electricity systems — but these strategies can produce a more rapid, more effective, and fairer energy transition.

For the first time in its history, the International Energy Agency (IEA) has projected a decline in global coal demand over its forecast period.

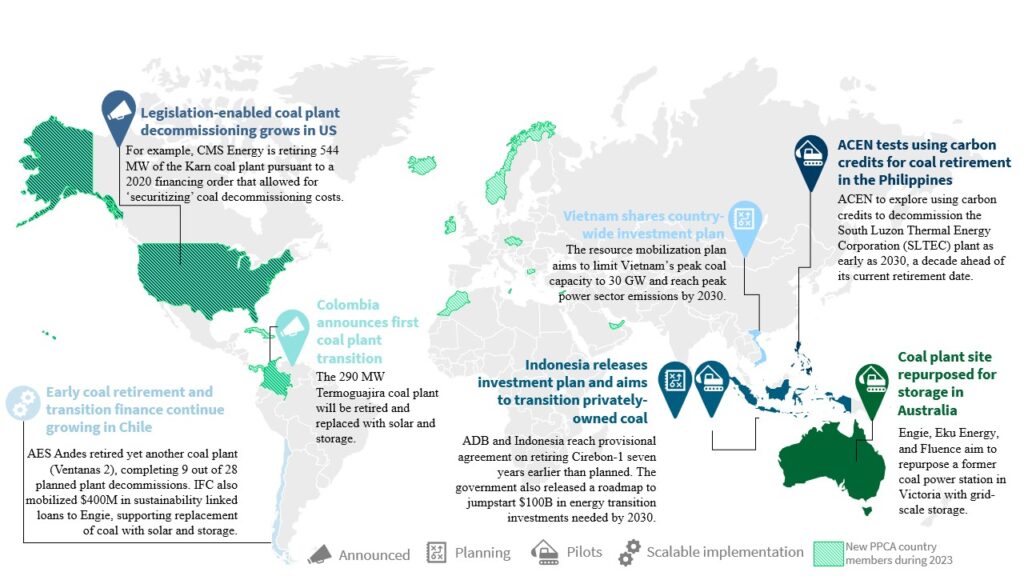

This promising outlook builds on a slew of actions from last year, ranging from the release of coal transition-enabling investment plans in Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines to the implementation of said transition in Southeast Asia, Oceania, North America, South America, and Europe (see Exhibit 1 below).

Exhibit 1 – Snapshot of progress on global coal transition in 2023

And while last year saw a shift toward early implementation of the transition, a few notable commitments were also made. There was an announcement to transition away from fossil fuels at COP28 and pledges from several countries (including the United States and Morocco) to develop no new coal and phase out existing unabated coal power.

Despite real momentum in this transition, however, coal power emissions reached an all-time high of 9.5 GtCO2 last year (see Exhibit 2). The rise in emissions can, to an extent, be seen as an overhang from a surge in coal demand in 2022 — driven by extraordinarily high gas prices, energy security concerns (particularly in China), post-pandemic economic recovery, and high interest rates that slowed clean energy financing.

Exhibit 2 – Coal power emissions in 2023 reached an all-time high even as plant buildout reached a near stop

Exhibit 2 also shows that the buildout of new coal power has slowed to a near stop — with over 1,900 GW canceled in the past decade, equivalent to 90 percent of today’s fleet.

These seemingly contradictory trends reflect the complexity of the coal-to-clean transition — how effective it ends up being hinges on ensuring ambitious climate action integrates priorities around energy security, affordability, reliability, and meeting growth in electricity demand. Below, we share five insights to help accelerate this transition, informed by RMI’s deep engagement in Southeast Asia and from partners working around the globe.

1. A rethink is needed on power sector planning and compensation practices

Ambitious climate action and robust economic development are both imperatives for the modern world, and, fortunately, they are increasingly intertwined. However, jointly achieving them requires a paradigm shift in the power sector. We need a multifaceted approach to transition planning that enables not just emissions reductions, but also lower costs, more economic opportunity, and greater stability in key institutions (see Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3 - Multi-faceted approach needed for power sector transition planning

This requires revisiting how power plants are planned for, compensated and operated:

- Incorporating finance into resource planning: Transition finance is critical to decarbonizing the power sector, particularly in emerging economies. Successful grid planning that improves affordability and reduces emissions must incorporate financing needs from the get-go and expand traditional modeling approaches.

- Rewarding new ways to decarbonize the grid: New regulatory and contractual structures are needed to enable a wider array of power sector transition pathways. The value that storage and virtual power plants add to the grid, for example, needs to be recognized and compensated. This should be coupled with greater access to technology and cheaper financing, both of which would unlock their use in the Global South. As a last resort, flexible use of coal power for a limited period could be considered when no cheaper and cleaner alternatives exist.

2. Country platforms will continue playing a role — future efforts must focus on political buy-in and good process

Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs) are a recent and innovative approach to country-led transition efforts with $48 billion committed to support efforts in South Africa, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Senegal.

Through involvement in multiple JETP planning processes, RMI has identified key lessons to consider for future country platforms:

- Upfront planning is crucial. It is important for analysis and stakeholder alignment to occur prior to commitments and announcements. Such planning creates a shared understanding around 1) financing needs, 2) financing availability and, 3) the shape of the power sector transition, given the grid’s physical limits. Upfront planning also enables buy-in across institutions (e.g., utilities, government agencies) that are key to successful implementation.

- An integrative process strengthens ambition. Policy changes and financing needs are interrelated, and grid reliability informs and constrains all transition efforts. This requires carefully interconnecting and sequencing various stakeholder discussions.

- Sustained political momentum is central to success. Country platforms like JETPs are susceptible to shifting geopolitics and continuing to build consensus and sustain political momentum in recipient countries is necessary for success. This could be achieved by:

- Centering the developmental priorities of recipient countries and involving local stakeholders early and often in planning.

- Implementing local projects, in tandem with planning processes, that improve affordability and grow the local economy.

Given country platforms can spur a country’s transition, their successful implementation matters — they can bring in more just transition funding, raise ambition to slash emissions, lower costs for end-users, and kick-start a virtuous cycle of investments.

3. Meaningful coal transition progress occurred through more channels than ever before — this should continue

Last year saw significant diversification in coal transition efforts globally. This helps sustain momentum for the transition and must continue because:

- Each funding model brings its own risks. JETPs, for example, carry significant geopolitical risk. Moreover, other funding avenues for country-level efforts exist — the Philippines, for example, worked with Climate Investment Funds to release a $2.7 billion investment plan for power sector transition. Such efforts could be complemented by plant-level initiatives that also leverage philanthropy and the private sector, like ACEN’s coal plant pilot.

- Each country will have a unique transition. Various factors — economics of clean power, access to capital markets, climate legislation, geopolitics — inform a country’s approach to transition, and concessional, multilateral financing may not be suitable for all.

- The Polish Treasury, for example, had sufficient fiscal space and appetite to establish a state-owned entity and begin purchasing coal plants from the largest owners in the country. With the new government this plan might evolve, but it is still on the political agenda.

- Diverse and innovative efforts can accelerate grid transformation. Tackling the transition across geographies, at the plant and system level, and in different power sector paradigms, allows practitioners to understand and address the challenges of implementing such a multi-faceted transition more effectively.

- In Chile, Engie is exploring the use of a sustainability-linked loan to decommission and replace coal power with solar and storage.

- In the United States and Australia, efforts are underway to leverage legacy grid infrastructure at coal plant sites for clean power replacement.

4. Ambitious policymaking and transition financing are both needed and can reinforce each other if designed well

The question of what comes first — the right enabling environment or the necessary financing — is not new, especially for emerging economies. Ultimately, both are needed and can reinforce each other in a virtuous cycle.

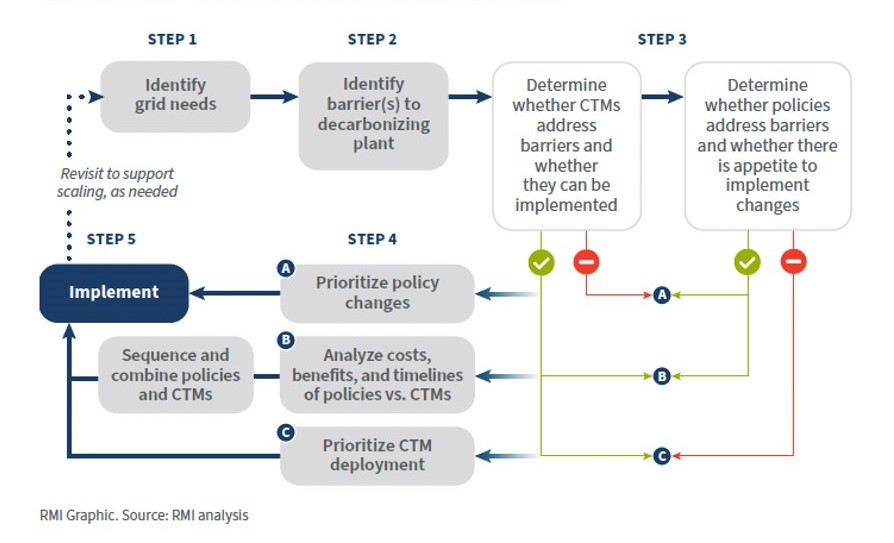

To do so, it is important to start by identifying the specific barriers to coal plant transition (e.g., decline in plant owner earnings, or high costs for taxpayers). Then, as RMI’s framework in Exhibit 4 shows, one must assess the viability of policy changes and financial mechanisms (coal transition mechanisms [CTMs]) in addressing those barriers — either individually, or together.

Exhibit 4 - Decision framework to integrate policy and finance for a rapid and effective coal transition

Through analyzing replacing Indonesian coal power contracts with clean ones, RMI found that policy changes alone could result in 60 percent emissions reductions versus business as usual, even with commercial financing. If one thoughtfully combined these changes with CTMs, that figure goes up to 90 percent.

Indonesian decision makers recognize this — the country’s JETP document has proposed changes to clean energy procurement processes, potentially improving the viability and speed of the country’s transition.

5. Credibility of and access to coal transition financing is essential — it requires reorienting sustainable finance metrics and standards to encourage investor participation

Growing the scale of the coal transition requires a surge of investments — considering transition finance as part of a broader power sector portfolio can strengthen the financial case for investment.

However, another reason transition finance has been insufficiently capitalized is reputational risk. Financers are uncertain about these deals achieving real emissions reductions and are wary of the ensuing blowback if they don’t deliver. This risk can be mitigated through:

- Robust methodologies and standardization approaches. Transition finance has, until recently, been missing from investment taxonomies. As it is increasingly included, developing robust underlying methodologies and aligning on standardization approaches will be critical to avoid emissions “leakage” — wherein emissions decline at the plant level but remain unabated at the system level.

- Engagement-focused finance policies. Active engagement — not divestment — is needed from shareholders and investors to transition existing coal power. The prevalence of coal exclusion policies and financed emissions targets, in particular, disincentivize financial institutions from doing so.

Looking to the future

The global energy transition and strong economic development can and should go hand in hand. In partnership with others, RMI will incorporate both priorities in its on-the-ground support this year, which will focus on a coal-to-clean transition in Southeast Asia, South America, and beyond.