Using Undergrid Minigrids to Drive Development in Thousands of Sub-Saharan African Communities

Throughout sub-Saharan Africa, hundreds of millions of people live “under the grid,” where they are nominally served by a utility but receive little or no power. For example, in Mokoloki community in Ogun State, Nigeria, electricity arrives sporadically; residents can only access power for a few hours at a time, and only a couple of days per week.

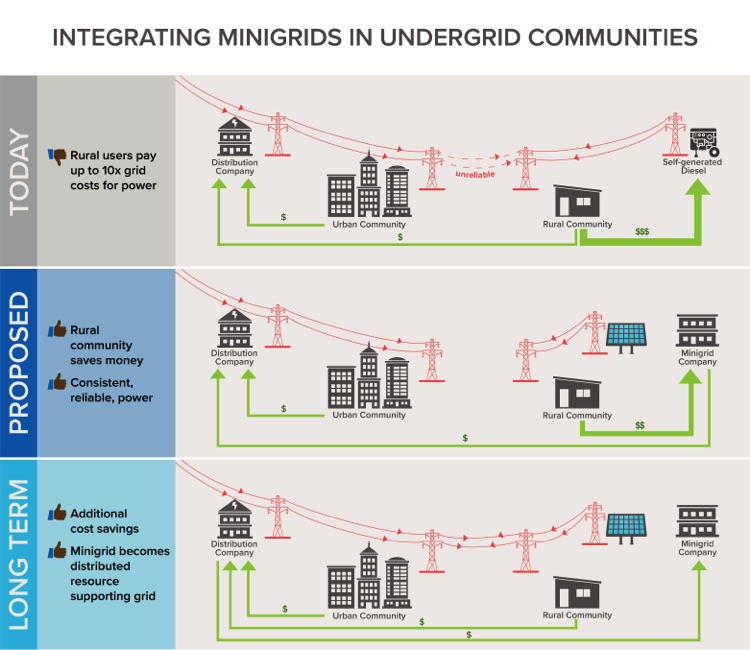

Undergrid communities, which receive unreliable and low-quality grid service that does not meet their needs, face a predicament. The lack of reliable power limits local development and modernization, forcing people to rely on expensive, polluting alternatives. African utilities, which often face financial hardship, have struggled to improve this situation. This is where we see an opportunity: across Africa, minigrids offer untapped potential to fill that void and provide undergrid communities with clean, reliable, and affordable power. As the grid improves, these minigrids can then be integrated as distributed energy resources that improve the reliability and resiliency of the entire system—a transition that is already beginning in more fully developed grids.

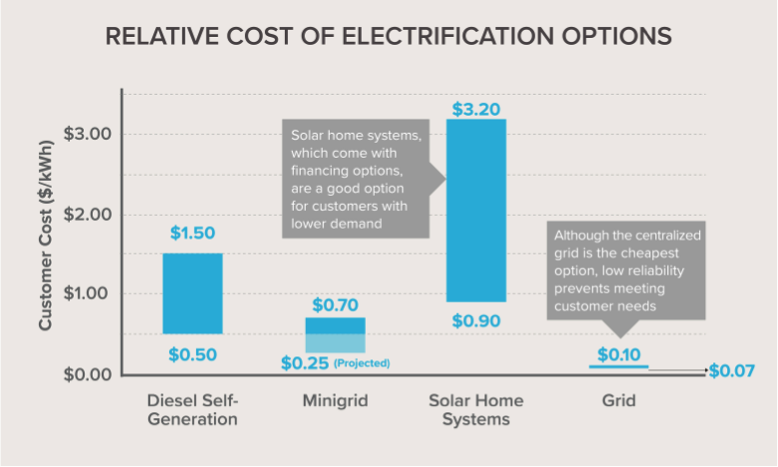

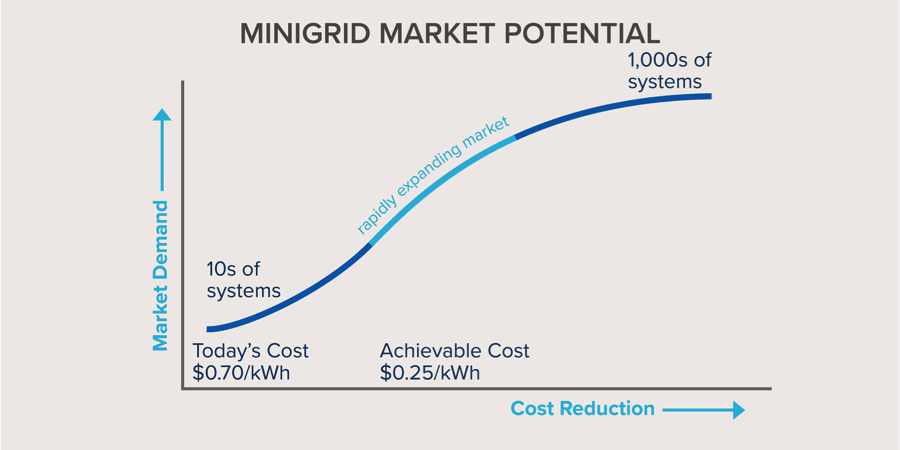

Rocky Mountain Institute’s Africa program believes minigrids are a key component of integrated energy planning to achieve sustainable economic growth. With partners, we have been working to identify and address key barriers limiting minigrids from supporting effective electrification in Africa. Our work in Nigeria shows that minigrids are already a least-cost option for powering many undergrid and near-grid communities. And, by growing new markets like those that are undergrid, the costs of minigrid-supplied power can rapidly fall more than 50 percent and enable minigrids to graduate from niche product to mainstream electricity source across sub-Saharan Africa.

Undergrid minigrids would address a new market segment

What is an undergrid community?

Communities under the grid are within the territory of an electric utility where the distribution network is at least nominally present. Like Mokoloki, some undergrid communities are served for several hours a day; others do not receive any power, despite the presence of little but remnant distribution infrastructure that indicates utility jurisdiction. Often designated as “underserved” by governments, residents in these communities rely on expensive alternatives like small diesel or gasoline generators to fill the gap between limited grid power and their real needs. Their demonstrated high ability to pay for alternatives and significant electricity demand are key factors differentiating undergrid from off-grid communities (where there is no grid presence at all).

Undergrid communities are ubiquitous across Africa. In Nigeria, rural communities like Mokoloki have high economic activity and ability to pay for power, but economic growth is limited by the electricity shortfall. In peri-urban areas of Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania, low grid reliability often stifles economic development. Even in the outskirts of cities like Freetown, Sierra Leone, limited generation capacity renders the grid insufficient to support the budding commercial and industrial activities that drive the country.

How do minigrids help?

Electricity access is closely linked to economic development. In communities where the grid is unreliable, customers are forced to supplement their grid-supplied electricity with expensive alternatives or go without power. These communities need new and innovative electrification options, like minigrids, to complement the unreliable main grid. In the near term, this would reduce customer costs and enable local economic development, while allowing utilities to focus on improving grid operations elsewhere. In the long term, undergrid minigrids would create a legion of distributed generation resources that can interconnect to support a more resilient grid structure.

What’s limiting minigrid success?

While undergrid minigrids are an ideal solution for many underserved communities, they haven’t been implemented in sub-Saharan Africa. A lack of policy and regulatory clarity is partly to blame for steering minigrid developers away from the undergrid market. Only six of approximately 50 sub-Saharan African countries have published specific regulations on minigrids. Of these, only one (Nigeria) specifically provides for undergrid systems. Developers see a risk in being overrun by the grid and are often encouraged by governments and funders to build systems far away from existing infrastructure. Even in India, where undergrid minigrids have been built, developers still perceive high risk in them and avoid collaborating with the utility.

An additional problem stems from the fact that undergrid communities, despite receiving poor electricity service, are nominally considered to be connected to electricity. This reduces the emphasis from development partners and others that are primarily focused on the number of connections as a metric for success of their programs.

The Nigerian market offers a compelling case for undergrid minigrids

Nigeria offers a promising opportunity for demonstrating undergrid minigrid success. A supportive federal policy and regulatory environment has created unique circumstances to test and implement new electrification approaches. Undergrid minigrids, in particular, can fill the gap left by insufficient and unreliable grid power. According to Power for All, 80 percent of grid users in Nigeria already supplement unreliable electricity. Since underperforming distribution companies have limited capital to improve service to rural customers, they are willing to explore new solutions.

Nigeria’s undergrid market has enormous scaling potential. At a recent RMI convening, developers and other stakeholders estimated that there are as many as 10,000 undergrid communities appropriate for minigrid implementation in Nigeria, representing an investment opportunity on the order of $5 billion. Residents in these communities are eager and ready to pay for new reliable and affordable sources of power—and minigrids are cost-competitive.

The market for undergrid minigrids is waiting for someone to act.

The minigrid market is set for an injection of capital to unlock project development—grant funding is available, but implementation has been slow. Despite the risks inherent in a young industry in developing countries, undergrid projects are a particularly compelling investment opportunity for impact investors, foundations, and early stage venture capital. Developing the large undergrid market will help accelerate broader minigrid growth by helping bring down the average system cost to $0.25/kWh.

Despite the added complexity of working with utilities, there is a strong business case for working in undergrid communities. Undergrid communities are a large and attractive market segment that is thirsty for the clean, affordable, and reliable electricity minigrids can provide. If Nigeria is representative of the region, undergrid development may be the biggest off-grid opportunity in sub-Saharan Africa, with the potential to address the needs of tens of thousands of communities. And as the market grows, minigrids—whether isolated or interconnected with the grid—will become significant distributed energy resources that enhance sustainability and resiliency across the continent.

RMI is actively working with developers, utilities, and governments in sub-Saharan Africa to unlock undergrid minigrid development by demonstrating that utilities and developers can effectively work together to mutual benefit. With a proven business case leading to falling minigrid costs, the undergrid minigrid solution can scale to provide reliable and affordable power to millions of people throughout sub-Saharan Africa and beyond.

Katie Lau, Eric Wanless, Kelly Carlin, and Stephen Doig contributed to this article.