Unwrapping Coal in 2022

A look back at coal transition finance this year.

It has been a tumultuous year for the coal transition. Global coal emissions are poised to break all-time records as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and droughts continue to disrupt energy supplies. But 2022 also set a record for retired and canceled coal capacity (Exhibit 1), and coal phaseout ambition continues to grow — even in the face of present energy challenges. For example Germany, despite restarting or extending the use of some coal plants due to its current energy shortage, is maintaining its commitment to a 2030 coal phaseout deadline, and German utility RWE committed to close its last remaining units by the same deadline. Today, over 95 percent of global coal consumption is in markets with a commitment to coal phaseout or net-zero emissions (Exhibit 2). Renewable capacity additions also hit an all-time high, generating cost savings and benefits to energy security — in contrast to volatile and rising coal prices, which in part led Korean utility KEPCo. to announce the sale of its overseas coal assets.

Finance has emerged as a key lever in accelerating the coal-to-clean transition, as major coal transition mechanisms (CTMs) and deals have been announced across the globe. Alongside policy, finance is a critical tool for the transition as most of the world’s coal plants are shielded from competition with clean energy. With all the excitement over CTMs, it’s hard to make sense of what they mean. Here are four questions we asked ourselves — and our view on where things should head next.

1. How far have we come in financing the coal transition over the past year?

In 2021, there was a significant increase in momentum in the transition away from coal, as COP26 marked the first time coal phase down was included in international climate agreements. The conference also saw the announcement of several major coal transition programs, including in South Africa (Just Energy Transition Partnership [JETP]), Southeast Asia (Asian Development Bank’s [ADB’s] Energy Transition Mechanism), and globally (Climate Investment Funds [CIF] Accelerating Coal Transition), opening the door for finance to play a key role in the global coal transition.

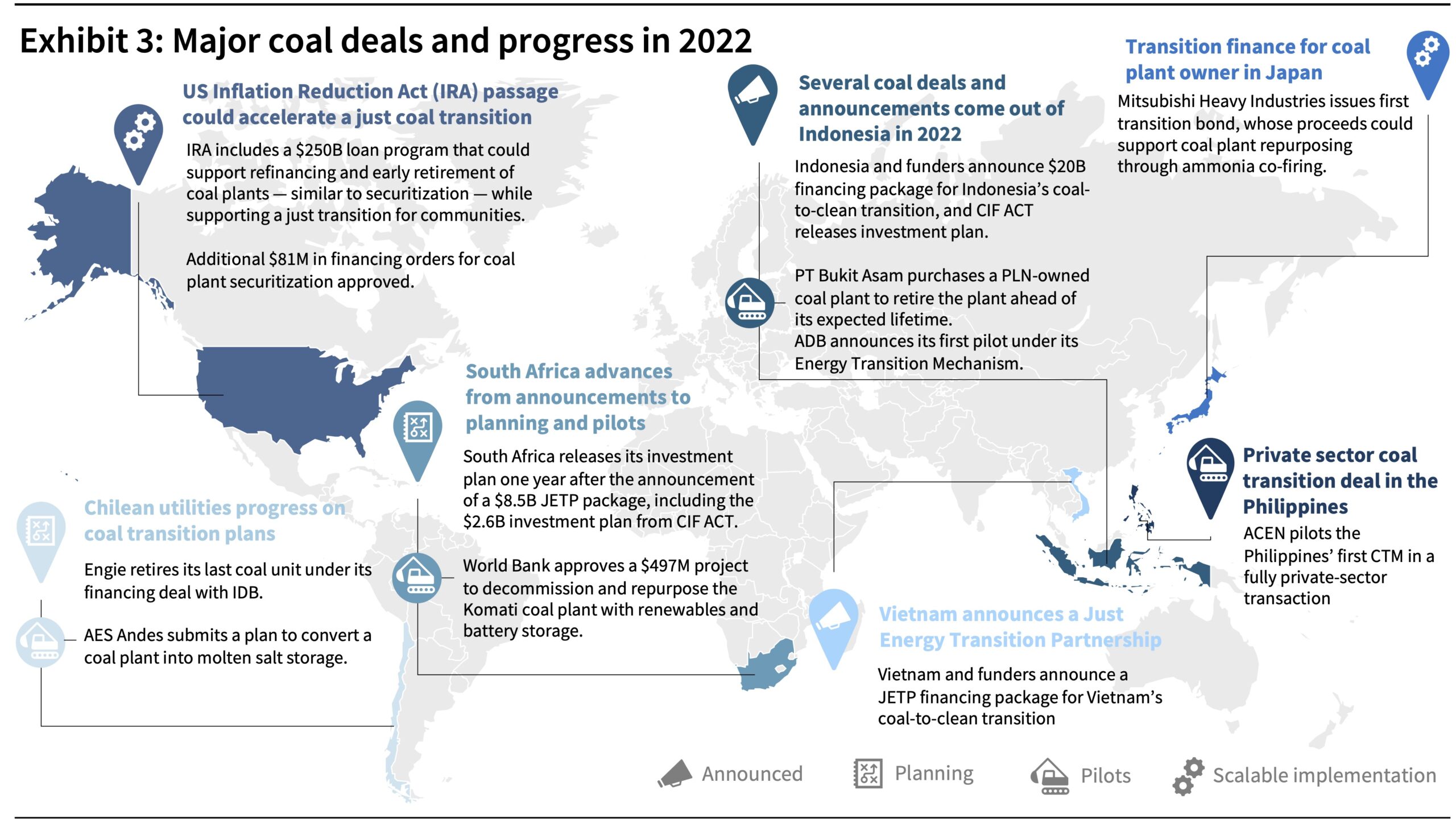

Building on this momentum, this year we saw the development of detailed investment plans and pilots, while new commitments more than quadrupled the amount of coal transition finance in the past year (Exhibits 3 and 4). Most recently, Vietnam and the Group of Seven (G7) nations jointly announced a $15.5 billion JETP aimed at kickstarting Vietnam's coal-to-clean transition. Meanwhile, markets where CTMs were already established continued to mature, notably in the United States, where the Inflation Reduction Act included a loan program that can help retire coal plants while reinvesting in coal communities.

2. The devil lies in the details — so what do the details say?

In the past two years, $45.2 billion has been committed for the coal-to-clean transition, with the biggest financial packages going to South Africa, Indonesia, and Vietnam. These large sums continue to grab headlines, but here are three important takeaways to help put them into context.

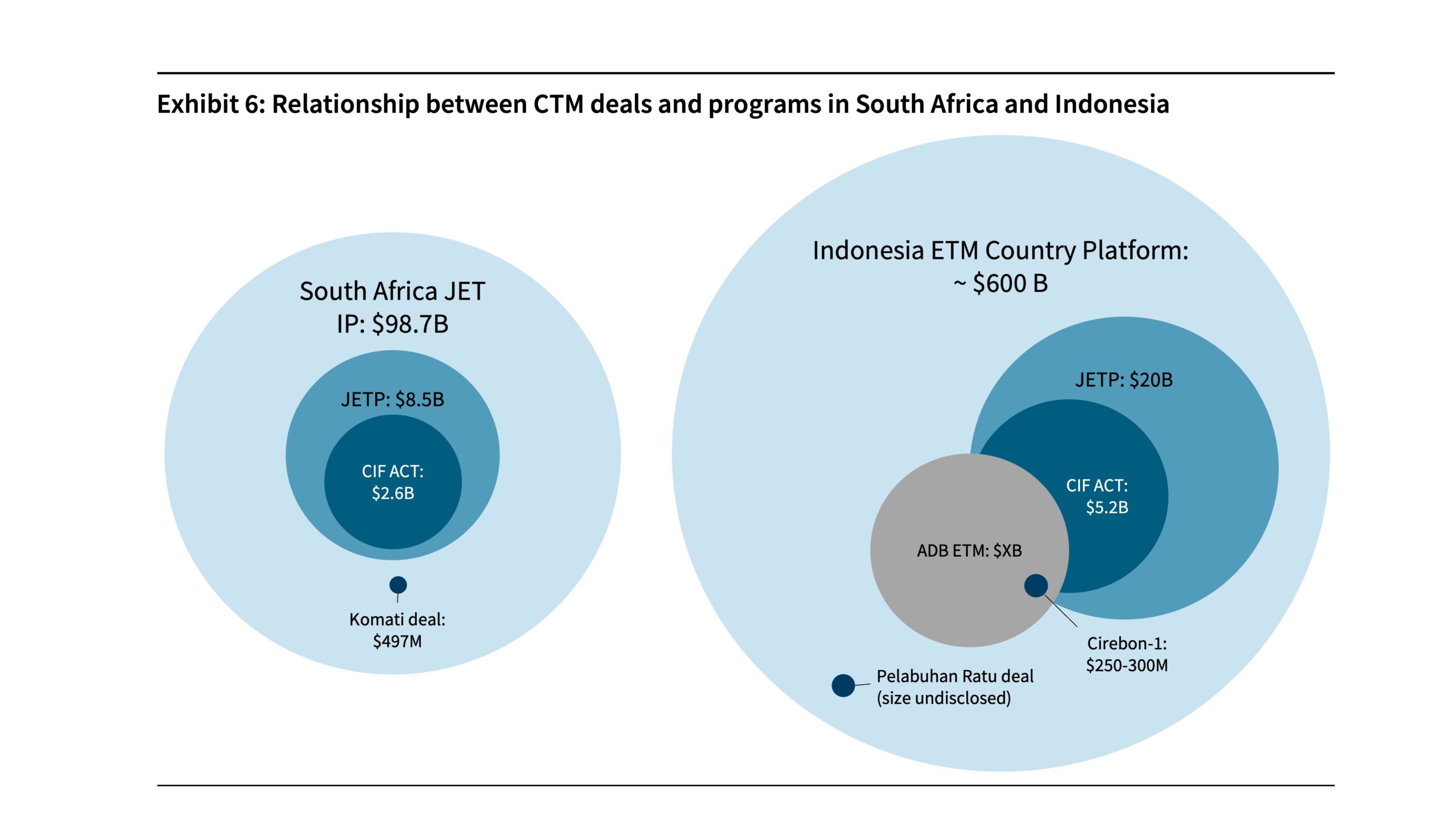

First, the CTMs announced — while significant — are still only stepping stones to the large amount of transition finance needed. For example, South Africa’s Just Energy Transition Investment Plan (JET IP) outlines an investment need of $98.7 billion over the next five years compared with the $8.5 billion committed to date. However, the success of this initial $8.5 billion — and that of other CTMs announced globally — may prove crucial if they are able to help create the proof points and enabling environments needed to catalyze further capital to bridge the funding gap.

Secondly, transition finance is about much more than coal phaseout, which is often just a fraction of the investment needed. Instead, it is about supporting a system-wide transition including coal plant phaseout, new clean energy infrastructure, just transition efforts, and capacity building and implementation. The South African JETP for example (Exhibit 5) includes funding for just transition, capacity building, and implementation. These activities are crucial but don’t generate returns, requiring grant funding to execute. As the current JETP contains only a small amount of grant financing, the share of grant funding in future CTMs will likely need to expand along with scaling private capital to finance the activities that do generate returns (managed phaseout, new RE development). Despite additional grant financing being a key sticking point in the negotiations of the Vietnamese JETP, public funding in the final package is likely to come largely in the form of concessional debt.

Finally, most of the $45.2 billion in finance committed to the coal transition over the past two years comes from just three separate financial packages: the South African, Indonesian, and Vietnamese JETPs. A global coal-to-clean transition will require broader engagement and more diverse funding, as public concessional dollars can be limited. This will spotlight our ability to utilize concessional financing in a way that catalyzes additional capital from international and domestic private financial institutions. We’ve already seen an increase in the share of private finance in JETPs, as half of the committed funding in Vietnam and Indonesia is expected to come from the private sector, compared to under 20 percent in South Africa. In the Philippines, the fully commercial private ETM led by ACEN shows the willingness of private capital to finance the coal transition, given assurances that their investments will lead to emissions reductions and provide returns.

3. How do the coal transition packages interact and relate?

The ~$45 billion in coal transition financing has been provided through different channels, targeting different levels of the energy transition, from broad country programs to specific asset-level pilots — Indonesia and South Africa are good examples of geographies with multiple CTMs and different financiers (Exhibit 6), and we’re likely to see a similar dynamic for Vietnam once more details about their Resource Mobilization Plan are released.

Ultimately, the coal transition needs to be driven both from the bottom up and top down. Asset-level transactions like the Komati and Cirbeon-1 deals are important to get work done early on-the-ground, while providing learnings for future transactions and informing decision-making processes in larger country programs. For example, cost estimates for coal plant phaseout and just transition efforts in the South African JET IP were created based on the real costs of the Komati pilot, scaled for plant size. Similarly, the decision by ADB to “refinance and retire” the Cirebon-1 plant rather than “acquire and retire” (targeting a change in ownership) like in a traditional ETM was made as ADB engaged with the plant owner and recognized the value of a simpler CTM structure.

Top-down efforts are needed to connect near-term pilots and plans to a broader roadmap that mobilizes the scale of transition finance needed and achieves system-wide emissions reductions. Support at the country-level will enable the coordinated planning, capacity building, and governance of the transition to ensure it is managed and just, and to map out long-term investment needs. For example, Indonesia is using its ETM Country Platform to connect different coal transition financiers (foreign sovereign donors, ADB, CIF, private financiers) to coal asset owners (utilities and IPPs).

4. What exactly are the deals promising — and can they deliver on those promises?

In the wake of CTM announcements often comes a slew of questions about the deal: what is the emissions impact, how much did the deal cost, and are those “good enough?” Many of these questions tie to the deal’s credibility, from how a deal is scoped and financed to ensuring financing packages deliver not just financial returns but also climate and social outcomes.

While RMI, Climate Policy Initiative, and Climate Bonds Initiative have provided emerging guidance on what constitutes a credible deal, assessing credibility requires transparency in the process of developing a deal, its final design, and implementation. The deals that took place in 2022 both leave room for additional improvement and mark a step up from previous announcements — from CIF’s release of Indonesia’s draft investment plan for public comment, to ACEN’s and ADB’s disclosure of deal size for specific assets. Moving forward, greater transparency — including about key assumptions (including cost calculations) and expected impact — will not only help underpin credibility but will also be critical to enable collective learning about CTMs.

Remaining questions for 2023

Moving into 2023, we look forward to seeing CTMs continue to mature. As they do, we hope to find answers to more questions, including how private capital can be better mobilized; how the just transition will be prioritized, financed, and implemented; and how pilots will align with emerging electricity, investment, and just transition planning processes.