Transition Credits Are Gearing Up to Support Global Energy Transformation

A new type of carbon credit for the global energy transition could work. Here’s how.

The idea of buying and selling carbon credits — permits that represent one ton of carbon dioxide removed from the atmosphere — to incentivize climate change mitigation activities has been around for almost 50 years.

However, as global attention continues to focus on the climate mitigation impact of the phase-out of fossil fuel-fired power generation, a new type of carbon credit to drive the energy transition is being developed. So-called “transition credits” monetize the reduction or avoidance of future emissions from a project — such as the early retirement of a coal plant — or even an entire jurisdiction.

If done right, transition credits could fill a critical funding gap for emerging markets and developing economies in their shift to a rapidly deploying, global clean energy economy.

The need for energy transition credits

In emerging markets, high costs of capital, inflexible regulatory environments, and young coal fleets with significant remaining asset value hinder the financial viability of early coal plant retirement and replacement. Innovative financial mechanisms can accelerate early coal retirement and support their replacement with low-carbon solutions, while mitigating the impacts on coal workers and communities.

However, in many cases the available commercial and public finance alone is not enough to incentivize impactful early retirement. Coal plants are often under contracts meant to maximize profits, and these typically outweigh the financial and public policy benefits of early retirement and emissions reductions to key stakeholders. This is where energy transition credits could come in. At the right price, they could provide the finance needed for early retirement.

These credits could be monetized through the global voluntary carbon market (VCM) or through national and international compliance markets, including the Paris Agreement Article 6 trading mechanisms that allow for trading climate ambition between countries and companies based on a country’s performance against their nationally determined contribution.

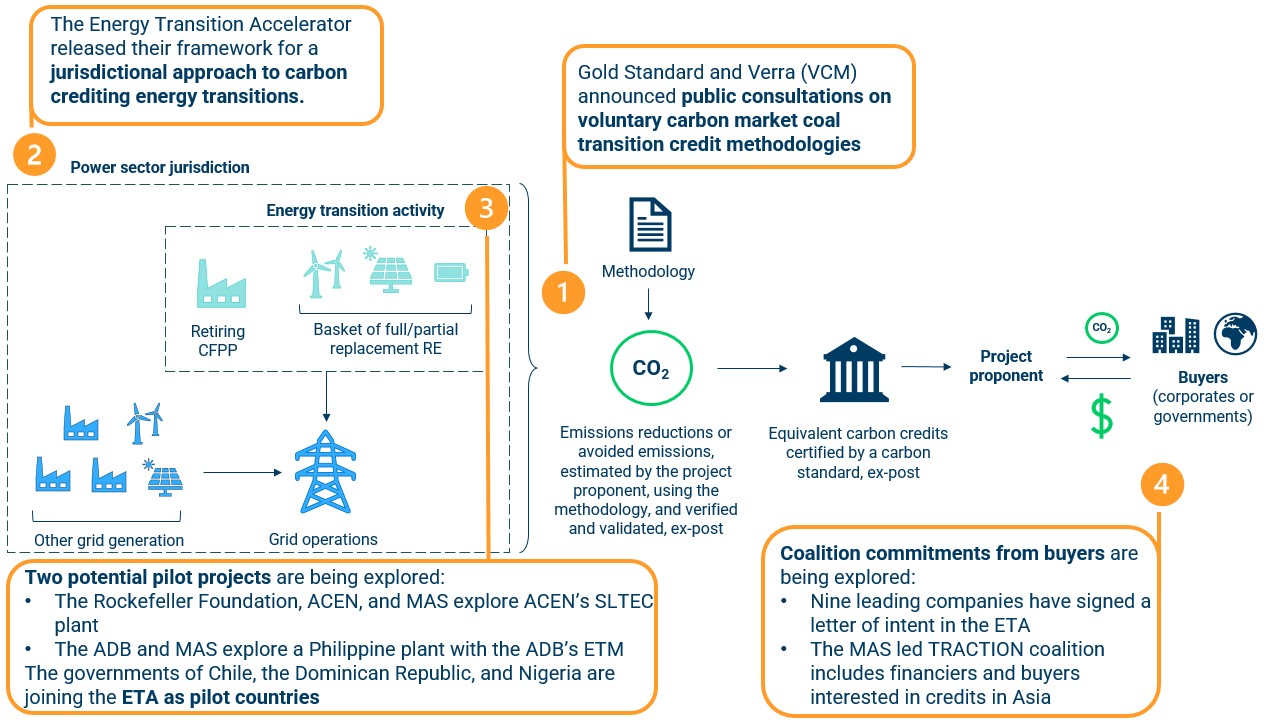

The state of play for the different transition credit initiatives is complicated, so we’ve broken it down using the graphic below. There are four big developments underway, including the refinement and stress testing of two different methodologies.

Where we are now

1. Project-based voluntary carbon credit methodologies

Two of the largest carbon standards, Verra and Gold Standard, have released methodologies for the project-based generation of voluntary carbon credits to support the early retirement and replacement of coal plants with renewable energy. RMI provided technical support to the Rockefeller Foundation-led Coal to Clean Credit Initiative responsible for developing the Verra methodology. These approaches quantify the net emissions reductions or avoided emissions within a specified project boundary — the early retirement of a coal plant and its replacement with new renewable power and/or the grid.

Ensuring a high level of integrity and quality of the transition credit, in line with the core carbon principles, has been a key design objective.

The retirement of a coal plant can only be additional if regulatory, financial, or economic incentives for retirement do not exist. Therefore, the technical life of the plant may not be a reasonable baseline scenario, particularly when renewable energy replacements become cheaper for a system operator than early retirement of a coal plant (including contract termination fees), or public or private coal transition financing is already available. This also means carbon credits are more likely to be financially additional in markets where coal plants are not in direct competition on a marginal cost basis with cheaper renewables.

Methodologies must also consider that it is likely that at least some of the replacement power for a coal plant will come from the wider grid, especially if the replacement resources are variable (i.e., wind or solar) or smaller in size. The emissions impact of this additional grid generation, or leakage, must be included in emissions reduction calculations. In these cases, requiring coal plant retirement to be in line with a jurisdictional integrated resource plan with a clear decarbonization pathway can also mitigate some of the risk that the retirement perversely incentivizes and “locks in” future gas plants as a dispatchable replacement resource.

Finally, early coal plant retirement can have a significant negative impact on workers and surrounding communities. To ensure alignment with sustainable development, methodologies must embed a robust approach to evaluate and mitigate the potential negative socio-economic impacts of the retirement. By requiring a minimum standard of just transition activities, transition credits can ensure that the projects provide protection and support for workers and communities.

The development of multiple methodologies at similar times and by different organizations has the potential to cause market confusion and undermine integrity goals, particularly where market players have misaligned incentives around the stringency of emissions reduction estimations. However, it also creates an opportunity for the methodologies to harmonize on sector-specific core integrity principles. Promoting market alignment on stringency can avoid a race to the bottom and protect the integrity of the credits. Frequent iterations of the methodologies and related public consultations will facilitate improvements in integrity as the market develops best practices on data collection, assessment techniques, and just transitions.

2. A jurisdictional framework (and how it compares with the project-based approach)

The US Department of State, Bezos Earth Fund, and Rockefeller Foundation have presented the core framework of the Energy Transition Accelerator (ETA) to support a jurisdictional, power-sector-wide crediting approach. This differs from a project-based approach by quantifying and monetizing the emissions reductions across a jurisdiction’s entire power sector over time, rather than just within a project boundary. As a result, it can incentivize a wide variety of transition activities including public policies and regulation, coal-to-clean power plant replacement, and grid infrastructure investment.

Project and jurisdictional approaches do not need to be mutually exclusive, however both approaches must carefully consider how they mitigate the risk of double counting emissions. Where there is a jurisdictional crediting scheme and transition credit projects operating at the same time, it is critical that the project methodology does not credit for emissions reductions driven by wider decarbonization policies that are incentivized under the jurisdictional approach.

3. Pilots

At COP28, five pilots were announced: two potential pilot projects for early coal plant retirement and replacement in South Luzon (SLTEC) and Mindanao in the Philippines and three pilot countries to the ETA (Nigeria, Chile, and the Dominican Republic).

These pilots can provide critical lessons to build confidence in these approaches if strong, transparent, independent structures for shared learning and iteration are put in place. Carbon credit financing may not be appropriate for all coal plants and pilot projects will be important to help the global community understand the opportunities and risks of this financing approach.

However, the socio-economic impact of the energy transition is likely to be significant and nuanced, and the pilots will need to consider advanced financing and strict monitoring and governance processes. Many just transition-related costs will need to be disbursed in advance of coal plant retirement to be effective. It will take extensive coordination and mutual agreement of responsibility across various stakeholders, and strong KPI monitoring, reporting, and verification processes to ensure effective implementation.

4. Buyer interest

Nine companies — Bank of America, Boston Consulting Group, Mastercard, McDonald’s, Morgan Stanley, PepsiCo, Salesforce, Standard Chartered Bank, and Schneider Electric — have signed a letter of interest in the ETA as an opportunity to support large-scale power sector transformation, while accelerating progress toward their own climate goals. In Asia, the TRACTION coalition led by the Monetary Authority of Singapore includes financiers and advisors with a focus on exploring avenues to build buyers’ confidence in high-integrity credits in Asia.

Buyers — both corporate entities and countries — have shown a willingness to pay for high-quality credits with a rigorous, verified data package, and are increasingly wary of credits that could expose them to allegations of greenwashing. The energy transition credit methodologies consider the parameters that yield high-quality credits, so, if implemented correctly, transition credits could meet buyer’s priorities and growing demand for high-quality, permanent, and additional credits.

Buyer demand is likely to hinge on the success of the initial pilot projects. Demonstrating the climate and socio-economic impacts of transition credits will go a long way toward alleviating buyers’ perceived risks and attracting more buyers. Restricting private sector buyers from participating in transition credit schemes based on their level of climate ambition also mitigates the risk of greenwashing claims and leakage (e.g., the ETA is excluding fossil fuel producers and those without 2050 net-zero goals).

There has been significant attention on voluntary carbon markets recently, with questions being asked around the credibility of credit claims, the integrity of market actors, and the ability of the market to deliver impact. However, steps are being taken to improve the capacity of VCMs to finance the required climate transition in a trusted and reliable manner. RMI and Climate Collective recently released the Voluntary Carbon Market Landscape Guide to provide perspective on the core challenges the market faces and demonstrate its potential. It could be a powerful conduit for climate remediation if data and process integrity can be maintained through credit generation, monitoring, reporting, and verification.

Closing the financing gap for emerging markets, developing economies

Energy transition credits should be considered as one possible mechanism among many to support the global decarbonization of the power sector and will be most effective when implemented in alignment with other financial and policy levers. Transition credits need to be quantified and generated with care and transparency, or they risk channeling limited climate finance to plants that already have the financial incentive to retire. If they aren’t executed in partnership with good-faith public partners and in consideration of impacted communities, they could exacerbate potential negative social impacts of the energy transition on vulnerable workers and their families.

This year, we’ll be looking out for 1) alignment on the stringency of core concepts across the project-based methodologies and stakeholder coalitions, 2) coordination on double counting risks between project and jurisdictional approaches, and 3) the transparent development of stronger community-focused monitoring and governance processes through the pilots to protect workers and communities. Moving forward on these pieces can provide the robust support that transition credits need to effectively mobilize and channel private and public finance to where it is most needed in the global energy transition.