To Cut Emissions, Azerbaijan Prioritizes Decarbonization of Oil and Gas

As the host to COP29, the country can lead by example by tackling its methane emissions.

With the start of COP29, host country Azerbaijan is in the spotlight. As an oil and gas exporter, it is facing heightened scrutiny over its climate commitments and emissions performance.

This level of attention for Azerbaijan — which ranks outside the top 10 or even top 20 oil and gas producing countries — is unusual. Larger oil and gas producers, including the United States, Saudia Arabia, and the COP28 host, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), find themselves in headlines far more often.

Yet Azerbaijan is like many middle-tier oil and gas-dependent economies that rarely show up on the radar but are integral to successfully achieving our global methane reduction goals.

A mid-tier exporter heavily dependent on oil and gas

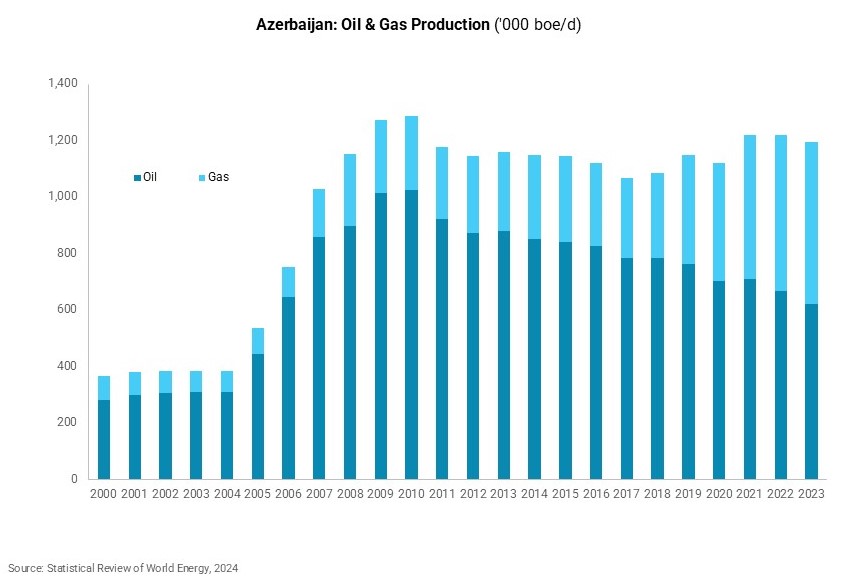

According to the Statistical Review of World Energy, Azerbaijan produced 620,000 barrels per day (b/d) of oil and 35.6 billion cubic meters (Bcm) of gas in 2023. Over the past decade, oil production has steadily declined, but rising gas production has compensated.

In the grand scheme of global markets, these volumes amount to less than 1 percent of total oil and gas production. The UAE produced four times more oil and gas. Saudi Arabia produced 11 times that amount. US oil and gas output last year was 30 times Azerbaijan’s. But Azerbaijan is an important regional oil and gas supplier to Europe that is stepping up its gas export commitments.

Beyond market considerations, Azerbaijan shares similarities with many oil and gas producing countries that collectively are essential to achieving our global methane emissions goals. With per capita gross domestic product (GDP) of $7,155 in 2023, Azerbaijan is squarely a middle-income country, like a range of other established oil and gas producers, including Algeria, Colombia, Ecuador, Equatorial Guinea and Gabon.

Even though Azerbaijan is not exceptionally wealthy, its economy is deeply reliant on oil and gas, which account for more than 90 percent of Azerbaijan’s total export earnings and over half of the government budget. The oil and gas sector makes up about 48 percent of Azerbaijan’s GDP – on par with Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Kuwait. In contrast to some deep-pocketed Mideast Gulf producers, Azerbaijan, like many mid-tier producers, is not flush with cash that it can readily deploy to decarbonization and energy transition priorities.

Azerbaijan’s methane emissions challenges

Azerbaijan ranks 30th on the International Energy Agency (IEA)’s Global Methane Tracker of oil and gas-based methane emitters (between Colombia and Ecuador). This does not make it inconsequential. While the top 5-10 emitters deservedly receive a great deal of focus, one-third of overall methane emissions comes from the long tail of producers ranked 10th-55th. Countries ranked 20th or lower collectively emit 10 million tons of methane — virtually on par with second-place Russia and more than Iran and Venezuela combined. Cutting oil and gas methane emissions 75 percent by 2030 will not be possible without Azerbaijan and others on this long list participating, especially given that some of the top emitters are not likely to act anytime soon.

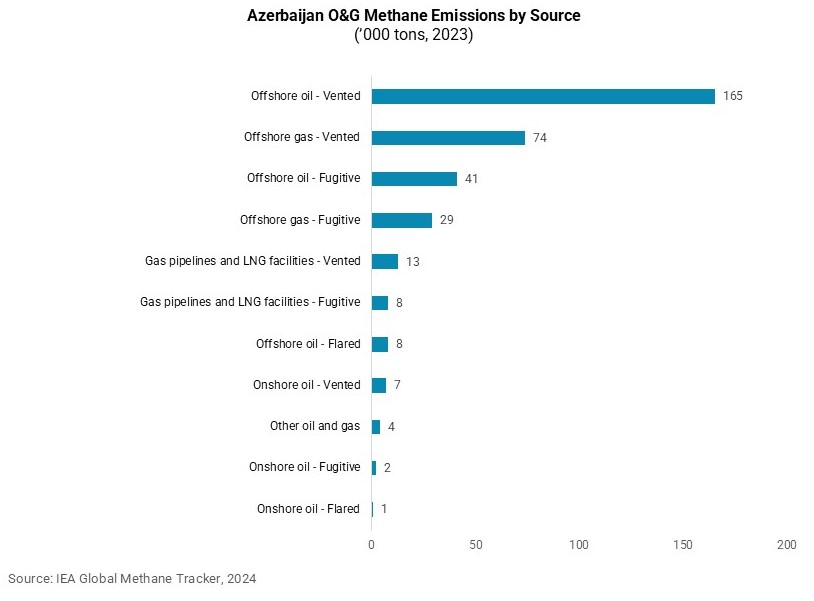

Like most other countries, Azerbaijan’s methane emissions come predominantly from venting rather than fugitive leaks, according to the IEA’s assessment. Vented methane from offshore oil and gas assets comprises two-thirds of total sectoral methane emissions — with offshore oil accounting for nearly 50 percent alone, as plotted below.

The distinction between vented and fugitive methane is important. Fugitive leaks usually occur randomly in routine equipment design, are unintentional, and are harder to measure and track. Vented methane tends to come from large open-system releases due to either inadvertent malfunctions or misguided, intentional operational practices.

Companies are in the process of better identifying where the largest volumes of methane emissions are coming from and why. An expanding system of new methane satellites being launched will only help in this effort. On one hand, venting at this proportion is a red flag. On the other hand, it presents Azerbaijan a major opportunity for near-term climate action.

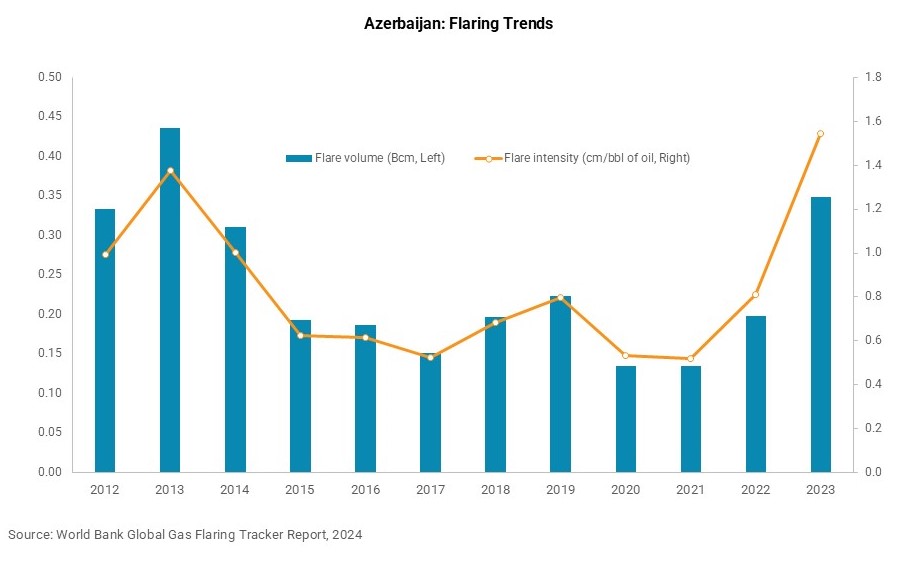

Azerbaijan similarly ranks 37th worldwide by total gas flared, between Uzbekistan and Colombia, according to the World Bank’s Global Gas Flaring Tracker Report and accompanying data. In contrast to methane releases discussed above, flaring is the burning of excess gas due to operational upsets or because an operator does not have the ability to bring its gas to market. When gas is combusted, it is mostly turned into carbon dioxide, which has a lower near-term impact on warming. But flares are not 100 percent efficient, and a portion of their emissions include unburned methane and other pollutants.

RMI’s analysis of VIIRS satellite data shows that about 60 percent of Azerbaijan’s flared gas volume comes from just two flares in offshore oil assets. This is not uncommon, as methane “super-emitters” and high-emitting assets tend to make up a significant share of flaring. Azerbaijan again has a clear near-term opportunity to reduce its flaring emissions significantly by dealing with these two sources.

Stepping up commitments, but ready for climate action?

Given Azerbaijan’s economic dependence on oil and gas, it would not be a surprise if it resisted calls to climate action. But Baku is striving to seize the moment.

The country took a big step forward at COP28 last December, when SOCAR, the Azeri national oil and gas company (NOC), signed the landmark Oil & Gas Decarbonization Charter (OGDC). Through the Charter, SOCAR aims to cut upstream oil and gas methane emissions to below 0.2 percent methane intensity and end routine flaring by 2030. As part of the OGDC, it also aims to achieve net-zero operational emissions (scopes 1 and 2) by 2050. Although SOCAR had set a net-zero goal in 2021, its OGDC goals go further in both ambition and concrete detail.

This year, SOCAR has taken a second notable step in joining the Oil & Gas Methane Partnership (OGMP) 2.0 — the flagship corporate methane emissions measurement and reporting framework overseen by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Through its participation in OGMP 2.0, SOCAR is starting down a path of improving its methane emissions disclosure, ultimately resulting in more measurement-based and site-level reporting.

Azerbaijan and SOCAR now face the daunting task of delivering on their goals. The reality is the NOC operates a small share of Azerbaijan’s total production. SOCAR operates 15 fields through its Azneft PU subsidiary, which collectively produce less than 20 percent of the country’s total oil and gas output, according to SOCAR’s 2023 annual report.

By far the two largest producing assets in Azerbaijan are the Azeri-Chirag-Gunashli (ACG) complex of oil fields and the Shah Deniz gas field. Together SOCAR reports that these assets account for 73 percent of its oil production and 81 percent of its gas production. UK major BP operates these fields in separate consortia with SOCAR and several other companies, including Hungary’s MOL, Japan’s INPEX and Itochu, Turkey’s TPAO, Russia’s Lukoil, Iran’s NICO, India’s ONGC, and the US firm ExxonMobil.

SOCAR and Azerbaijan’s climate commitments thus depend on the actions of BP and their partners. In some ways, this is an advantage for SOCAR. BP is an experienced operator that faces potential reputational risk and shareholder backlash if it fails to meet its emissions targets. The tradeoff, however, is that SOCAR does not have full control over assets that are core to its climate goals. Ensuring that there is shared will and alignment of incentives across partners is a critical task.

The case of Azerbaijan underscores the interdependence of countries, companies, and other stakeholders in delivering on system-wide goals like oil and gas methane mitigation and decarbonization. To be sure, each company should be responsible for the assets it operates. But it is equally important to recognize that durable solutions require extensive cooperation and collective action, especially in such a complex sector. As the host country, Azerbaijan can, for example, make a major contribution by supporting adding methane expressly into countries’ nationally determined contributions (NDCs) at COP29. We are in this together, whether we like it or not. This should not be an excuse for inaction but rather a motivation to redouble joint efforts to meet our 2030 goals.