There Is No Business as Usual: Decarbonizing Industry Must Start Now

We know that a higher-than-1.5°C pathway will result in severe natural disasters, including flooding, rising sea levels, hurricanes, drought, and lethal temperature exposures. The increasing regularity of these extreme climate events will create drastic stresses on food and water supply, with ripple effects including hunger, market disruption, increased migration, and social unrest. In addition to threatening our environment and physical well-being, these events threaten our economy. In the United States alone the estimated total cost of weather and climate-based disasters between 1980 and 2019 is estimated at $1.75 trillion.

The reality is that if we are not successful in achieving net-zero emissions by 2050, the health of the global economy is fundamentally threatened. And to reach net-zero emissions, it is critical to decarbonize industrial sectors. More than 40 percent of annual greenhouse gas emissions come from the energy-intensive sectors that produce and deliver the essential goods we use on a daily basis. This includes industries like mining, steel, cement, petrochemicals, and heavy transport through ships, trucks, and planes. Decarbonizing these industries is essential to meeting a 1.5°C target, and that can’t be done continuing with business as usual.

Avoiding Disruption

Continuing on our current trajectory, with ever-increasing greenhouse gas emissions, will lead us to a 4°C global warming outcome. This will initiate completely unforeseen micro- and macro-economic disruptions within the lifetime of industrial assets that are being built today. But arguably the most disruptive scenario of all, learning from the past six months of the global COVID-19 response, is insufficient collective action in the next decade. This could force decision makers into “panic mode” as the more severe implications of global warming become apparent. If anything, such an outlook will halt international negotiation and revert globalization, reducing the solution space for addressing climate change, and instead putting focus on national priorities such as securing supply and domestic job creation.

We will begin to feel the impact on supply chains well before 2050. These disruptions will come from things like feedstock shortages and water supply challenges, but businesses will also see changes in consumer needs as well as changes in markets due to climate-related disruption.

Industry is Essential

For the industrial sector, the coming 30 years will undeniably be different than the past 30 years in fundamental ways. According to McKinsey & Company, it’s virtually impossible to achieve a 1.5°C outcome by relying on technology alone, even with the introduction of carbon removal technologies. RMI, the Energy Transitions Commission, and other partners examined 12 different 1.5°C pathways, and not a single one relies fully on technology to continue the current standard of living.

Having any hope of achieving a 1.5°C or even 2°C pathway ultimately means using less of the things like steel, cement, and plastic that go into the products we use every day. But significant reduction in material demand suggests we will see demand peak, and then fall, for things like oil, natural gas, steel, coal, and iron ore. This will result in value destruction for major global commodities.

At the same time, entirely new commodity markets will emerge to support the decarbonization of industrial sectors. Hydrogen is emerging as a strong candidate for future zero-carbon fuels across industrial applications. And as CO2 is either captured from industrial facilities or directly from the atmosphere, a whole logistics chain of transportation and long-term storage will be needed. In this transition, traditional geopolitical influence driven by access to fossil fuels, such as coal (China), oil (Middle East), and natural gas (Russia), will fall apart and the global energy markets will be reoriented toward securing access to the cheapest available renewable resources.

Business as Usual Is a Bad Business Strategy

The risks associated with inaction might be uncertain in terms of timing, but they are not speculative. Given the amount of research and analysis that have gone into climate change over the past 50 years, it’s arguably one of the best understood business risks executives need to relate to in the modern economy.

However, corporations do not consider climate change to be a black or white topic, nor should they. To honor their fiduciary responsibility to their shareholders, they balance cost of action with cost of inaction. But the bottom line is that inaction in our industrial systems will lead to dramatic climate change.

Business as usual—not changing and assuming that change will not be imposed on us—is a planning scenario that has no intellectual integrity and absolutely no support in research. Evaluating investments against an unrealistic reference outlook is at best an academic exercise, especially for investments in assets with greater than 30-year lifetimes. Pretending that the alternative to investing in decarbonization is to simply lull along as we have in the past 30 years fundamentally underestimates the cost of inaction and overestimates the cost of change. If we want to avoid unprecedented challenges to the global economy we will have to deal with dramatic changes in technology and business models.

Needless to say, industry does not like unexpected change and neither do investors. However, change is okay if you can navigate it with maintained returns, or even better if you can outperform the market and generate above-average returns. So rather than avoiding change per se, it benefits business to avoid disruptive change; orderly transitions are better than black swan events. From that perspective, policymakers and multilateral political negotiations play an important role. While it is easy to criticize the Paris Agreement for lack of ambition and impact, it reduces some of the risk of completely unpredicted shifts in business environment.

The Only Constant is Change

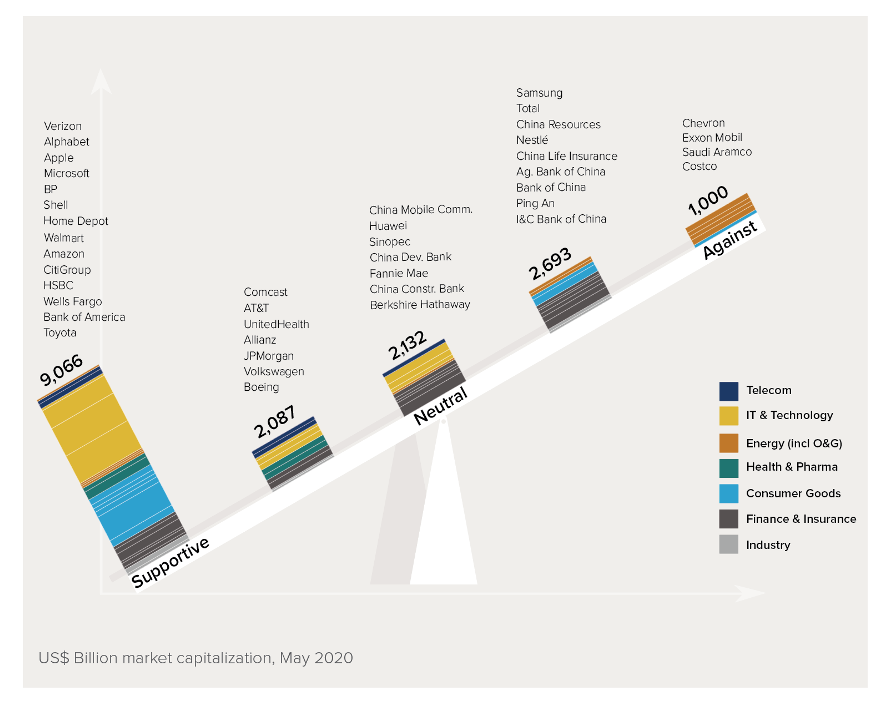

But while our current trajectory is bleak, there is hope. An increasing number of companies and countries are pledging to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050 or even 2040. Using market cap (or estimates thereof) as a proxy for market power, it is clear that the world in the past decade has experienced a significant shift in balance from strong influence of the fossil fuel industries (oil, gas, and coal) toward corporates committed to climate alignment.

Exhibit 1: Corporate Positions on Climate Change

Fast-moving consumer goods markets are already facing increased pressure around production practices and from investors. Investors are starting to take climate into consideration when making lending decisions. Financial systems and global financial institutions are increasingly considering climate alignment as a crucial factor for access to capital, resulting in new standards and disclosure frameworks that measure a company’s climate impact alongside economic activity. We are also seeing pressure for change from consumers due to direct strain from climate-related events and changing preferences. This will likely have a direct impact on consumer goods markets.

The transition away from fossil fuels will further marginalize the traditional energy sectors, accelerating said transition more, as political influence and financial incentives shift. As we see real change in traditional industries (e.g., HYBRIT recently opening up the first ever pilot plant for fossil-free steel), the question is not whether we will see major changes in global industry dynamics in the coming decades—but whether we will see it fast enough to secure a safe and resilient climate future.