Taiwan Makes It Easier for Global Companies to Procure Local Renewable Energy

Manufacturing powerhouse Taiwan has created a renewable energy credit (Taiwan-REC or T-REC) scheme that allows companies, including foreign companies, to procure directly from renewable energy projects. This is part of an emerging trend among countries vital to the global supply chain that will simplify corporate sustainability and stimulate the addition of renewables worldwide. Indeed, although Taiwan’s is a relatively new system, some companies are already procuring T-RECs to reduce their scope 2 emissions. These transactions have occurred at a small scale to date, and many buyers are watching the larger-scale power purchase agreement (PPA) market evolve.

Global companies are increasingly looking at their supply chains from a sustainability perspective. Apple, for example, is working with its suppliers to add 4 gigawatts (GW) of additional renewable energy globally, and Walmart launched Project Gigaton in 2017 to work with its suppliers to reduce its emissions by 2030 in the amount of, well, a gigaton. But where global companies have operations in nations with highly regulated electricity sectors, it can be very difficult to procure renewable energy locally or support the creation of local renewable energy supply. Such was the case in Taiwan, until recently.

Taiwan’s Move to Promote Renewables

Taiwan promulgated its Renewable Energy Development Act (the Act) and began stimulating renewable generation in 2009. New urgency was added to its quest for renewables after Japan’s Fukushima nuclear accident in 2011. Taiwan is a small and densely populated island of 24 million people, without much room to spare in the event of widespread nuclear contamination. So the decision was made to phase out nuclear power by 2025 (nuclear constituted over 10 percent of installed generation capacity as recently as 2015) and raise the targets for renewable capacity additions to 10–12.5 GW by 2030. That is an ambitious target for a nation with less than 50 GW of total generation capacity, and that had only 1.6 GW of renewable capacity in 2012.

To speed the country to its targets, the Taiwanese government created a feed-in tariff (FIT) program for new renewable energy generation. Initial rates are considerably higher than wholesale power prices in order to help kick-start the domestic industry, as with many FIT programs. For comparison, the peak cost of electricity in 2017 for large energy users was 3.24 Taiwan new dollars (NT$) whereas the compensation for power from ground-mounted solar was NT$4.55, for example. The FIT rates will decline over time, with the ground-mounted solar rate set to decline to NT$4.38 and then NT$4.29 over the course of 2018.

In addition to the FIT scheme, Taiwan amended the Act in January 2017 to create and support new markets for renewable power. The new law opened the country’s renewable energy sector to private renewable energy participation, and made it possible for nonutility buyers to procure T-RECs directly from projects or via newly enabled renewable energy retailers. This is a big change in a national market that had operated under a government-owned monopoly utility, Taiwan Power Company, or Taipower, since 1946. Taipower’s monopoly on fossil-fueled power remains, though there is speculation that a wholesale market may be introduced in 10 years or so. For now, the action is in the renewables sector.

The Mighty T-REC Is Born

In April 2017, Taiwan opened its National Renewable Energy Certification Center (T-REC Center) Preparatory Office to, among other things, establish a strict verification mechanism to ensure the credibility of T-RECs, and issued its first T-RECs in May 2017. The government also created a market platform to match buyers to sellers. Clearly, demand from companies existed before these structures were in place, evidenced by the first deals for T-RECs being signed within a few months of their creation.

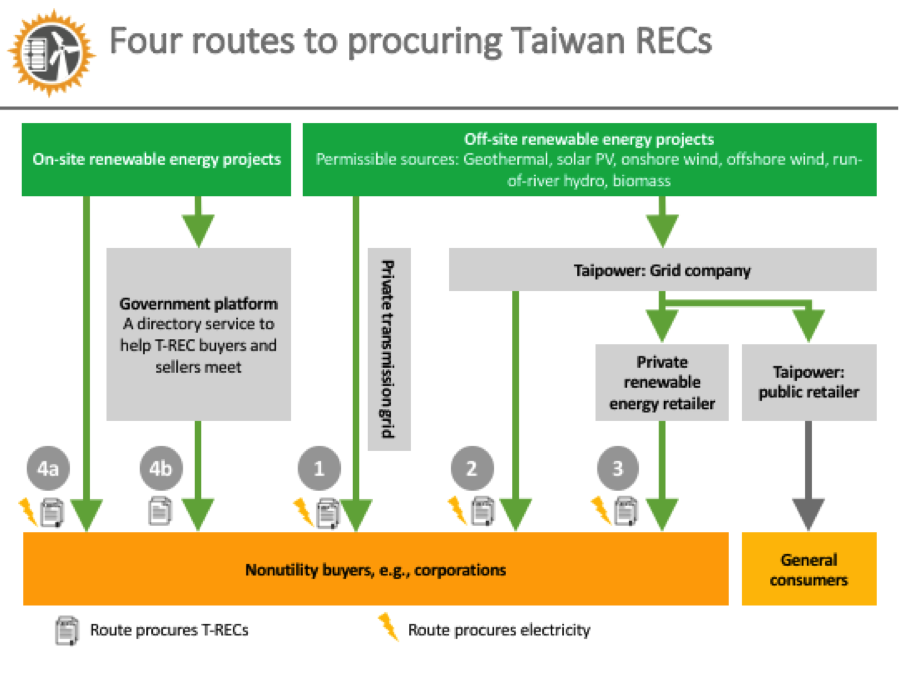

Taiwan’s REC scheme provides four methods, or routes, for nonutility buyers to procure T-RECs. The figures below illustrate the four available approaches:

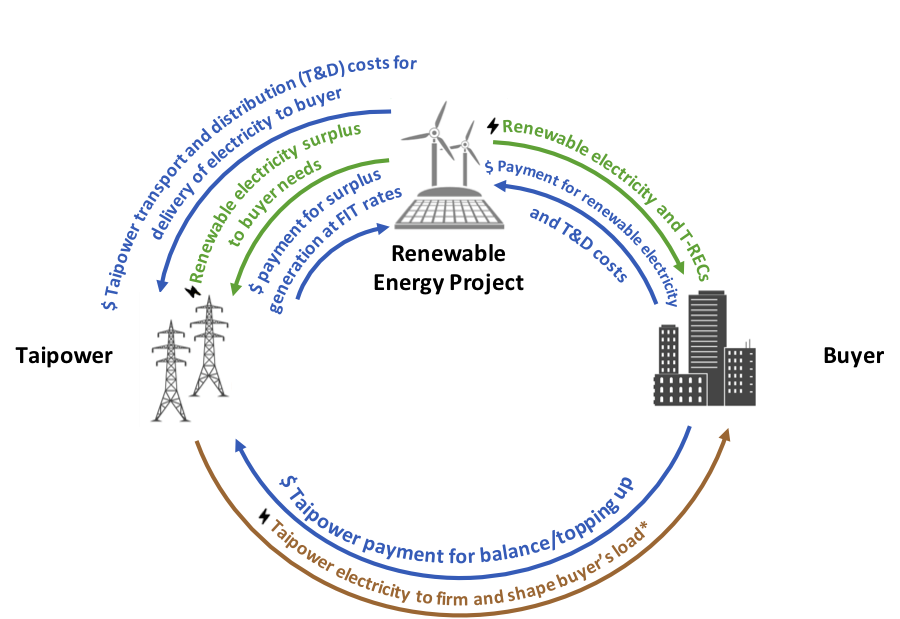

Routes 1 and 2 involve direct, bilateral power purchase agreements between renewable energy projects and nonutility buyers. Without a wholesale market, buyers in Taiwan are required to employ a direct/physical PPA and take title to electrons, instead of having the option to sign a virtual PPA for power that cannot connect to their facilities. The project owner pays for electricity wheeling to the customer’s site. Power is delivered through privately owned grid infrastructure (route 1), or delivered through Taipower’s grid infrastructure (route 2). Some multinational companies are already in discussions to procure renewable energy in Taiwan by these means, even as regulations are being finalized to clarify these routes. Figure 2 shows a simplified view of how costs and benefits might flow in route 2 transactions.

Note: It is assumed that Taipower is obligated to firm and shape the buyer’s electricity needs. T-RECs are deemed to have been retired as the buyer consumes the electricity unless the buyer opts to sell them on.

In route 3, retailers provide renewable energy supply options to nonutility buyers, and manage T-RECs procured from third-party generators. In route 4a, nonutility actors procure on-site generation at their own facilities and supply themselves with power behind the meter, claiming the T-RECs from the renewable energy generated at their own facilities.

Finally, in route 4b, nonutility buyers procure only T-RECs from sellers—without actually taking title to any electrons—and have the option to use the Taiwan National Renewable Energy Certification Center’s market platform to find sellers. Parties undertake bilateral negotiations to secure a contract for T-RECs, and T-RECs flow from seller to buyer, while the money that flows from buyer to seller stimulates additional renewable energy generation in Taiwan.

The First T-REC Success Story in Taiwan

The first company to do a T-REC deal was Cathay Financial Holdings (Cathay) a Taiwanese financial services group. Cathay used the last route, 4b, to procure. Cathay took an interest while the processes and regulations for securing T-RECs were still being developed. It began its first deal in May 2017, just one month after the T-REC Center opened. Because of the novelty of the procedure for all concerned, that first deal didn’t close until September. However, Cathay’s second and third deals, one of which was with a new seller, took only a single week.

Cathay was interested in T-RECs because it has committed to lowering its carbon footprint. Cathay’s interest dates back some years and is responsive to the expectations of its investors around the world. Cathay has fielded investor requests on the matter of carbon, as well as inquiries from the Carbon Disclosure Project.

When the T-REC Center opened, Cathay went through the steps required in route 4b. It submitted a form to the market platform detailing its interest in buying certificates. The market platform notified the T-REC sellers that were active on the platform and put Cathay in touch with them. Cathay then worked directly with the sellers to negotiate and execute their deals. When the deals were concluded, the sellers reported the volume of T-RECs in the deals to the market platform.

The sellers in Cathay’s case were two Taiwanese institutions that constructed solar projects on the roofs of their buildings and chose not to retain the T-RECs for themselves. The first seller was the National Marine Biology Museum, with which Cathay did three deals, and the second was the Industrial Technology Institute, in a single deal. The technology was not critical for Cathay; its primary considerations were price and ease of execution. Cathay is interested in transacting for more T-RECs and hopes that the volume of available T-RECs on the market platform will grow.

The deal team at Cathay found that securing internal buy-in to such a novel transaction was the most challenging part of the deal, an experience that most members of Rocky Mountain Institute’s Business Renewables Center can attest to. The company advises others following in its footsteps to start at a small scale in a low-cost, low-risk deal, and stresses the importance of having a dedicated corporate responsibility team to work with internal stakeholders to understand the reasons for doing such a transaction, which are not purely financial. The team at Cathay is pleased to have led the market, and shown that transactions are possible.

Market Growth Challenges Exist

As in other markets with a FIT or a similar system, renewable energy project developers have their choice of customers. They can sell electricity and associated environmental attributes to government or utility buyers, or to nonutility buyers, such as corporations.

In Taiwan, a sellers’ market has been created and is likely to persist while FIT rates remain materially higher than wholesale power costs. For many businesses, electricity costs are material, and an overnight jump in those costs would be difficult to absorb. This is likely to challenge any route where a buyer is procuring electricity along with the T-RECs.

A complicating factor is draft legislation that might mandate a high-energy user to procure a portion of its load from renewable sources. Given the current sellers’ market, nonutility buyers may find this mandate difficult to meet without complementary motivation of sellers or a FIT price comparable with wholesale power costs.

But these challenges notwithstanding, the market in Taiwan for local, reliable, well-regulated scope 2 emissions management through T-RECs is opening; local and international companies are looking hard at the opportunity this could afford. For the sake of their own competitiveness, and for the sake of the climate, this trend will hopefully grow to include more and more of the nations that are vital to the global supply chain. For now, Taiwan and a few others are showing the way.

Rocky Mountain Institute would like to thank Greenpeace Taiwan for its leadership in this sector. Greenpeace Taiwan is organizing a series of workshops for market actors to better understand their collective requirements, build bonds across the sector, and accelerate nonutility transactions with renewable energy.

Image courtesy of iStock.