Simple Tax Changes Can Unleash Clean Energy Deployment

According to the latest US government inventory, solar will account for 39 percent of the electric generation capacity added in 2021, and wind will constitute a further 31 percent. With current technology costs and policy incentives, renewables are now unquestionably the cheapest generation assets to build and operate. The levelized cost of new subsidized wind power is even cheaper than the marginal cost of running existing fossil assets fueled with today’s low-cost natural gas. (The levelized cost of energy, or LCOE, refers to the lifetime cost of a generation asset per megawatt-hour produced.) The LCOE of utility-scale solar is effectively a wash with existing natural gas generation.

Given these numbers, it comes as no surprise that developers have been rushing to deploy renewable energy projects. However, utilities have lagged behind in this race, especially with regard to solar. Regulated investor-owned utilities (IOUs), public power agencies, and cooperatives owned around 55 percent of total generating capacity in the United States in 2019 and 75 percent of the remaining coal capacity. But they owned only 15 percent of wind and 11 percent of the utility-scale solar. And despite the low cost of renewable energy, utilities continue to propose building new fossil-fueled capacity.

Why do utilities keep investing in fossil assets despite the availability of less expensive wind and solar? Part of the answer lies in tax regulations that prevent utilities from efficiently using the federal government’s most important clean energy incentives. Renewable energy’s growth has been driven by policy tools like the investment tax credit (ITC) for solar and both the Production Tax Credit (PTC) and ITC for wind. These incentives provide a credit that asset owners can use to offset the taxes that they owe the government.

Perverse Incentives for Utilities

However, the ITC and PTC are difficult for utilities to use. Not-for-profit public power agencies and many cooperative utilities do not pay taxes at all, so they have nothing to offset with tax credits. Most for-profit utilities have taken advantage of previous tax incentives—in particular, bonus depreciation measures that Congress repeatedly made available over the past two decades to combat economic downturns—and can already offset taxable earnings for many years to come using net operating losses carried forward from previous years. Even if for-profit utilities can make use of tax incentives, a legal restriction known as “tax normalization” requires them to keep the benefits of the ITC for investors rather than pass them along to their customers. The upshot is perverse: the same tax incentives intended to accelerate the clean transition are causing utilities to resist the switch to solar and wind.

Utilities must take a leading role in the energy transition. Reaching President Biden’s stated goal of 100 percent clean electricity by 2035 is necessary for the United States to achieve its commitment of 50–52 percent greenhouse gas reductions below 2005 levels by 2030. Although the scale of renewables deployment in 2021 is exciting, the president’s clean electricity goal requires an even faster pace. Properly incentivized, utilities can drive the renewables growth needed to meet President Biden’s climate change policy goals.

Two simple changes to the way we structure tax incentives can unleash renewables deployment to move at the speed necessary to meet these ambitious but vitally important goals:

- Eliminate tax normalization for the ITC, and allow the PTC in lieu of the ITC

- Provide direct pay of tax credits

Eliminate Tax Normalization for the ITC, and Allow the PTC in Lieu of the ITC

Normalization is a legal restriction within the tax code that compels regulated IOUs to keep the benefits of the ITC largely for their investors. Customers are allowed only to receive a fraction of the financial value of the credit, attenuated over the long operating life of their solar assets. In contrast, unregulated entities—such as renewables developers—are free to pass on the benefits of the ITC to their customers as dictated by market competition, a more economically rational way to balance the interests of investors and consumers. Put simply, because unregulated developers are not subject to normalization restrictions, they can sell electricity at lower prices, even when technology and capital costs are the same.

This pricing disadvantage has aligned IOUs—which sell electricity to nearly 50 million households and 7 million business accounts in every state except Nebraska—in opposition to solar development. Utility opposition can be explained by how regulated IOUs make investment decisions and earn profits. Before an IOU builds a power plant, it must prove to its regulator that the investment is prudent, considering the cost relative to other ownership options. Normalization rules make utility-owned solar projects more expensive for ratepayers and therefore less likely to be competitive with third-party assets that can price without the normalization penalty.

Third-party solar power purchase agreements are unattractive for IOUs, which earn profits for their shareholders by investing in and owning assets. IOUs therefore lack the financial motivation to accelerate solar deployment. Even if a particular IOU’s parent company owns an unregulated solar developer, its investors are likely to negatively view a shift of assets away from their low-risk regulated business to higher-risk unregulated assets. In this context, the IOU’s financial interests are likely best served by resisting the transition to solar.

Removing tax normalization restrictions for the ITC would realign the incentive to make solar development beneficial for IOUs. This simple change can meaningfully accelerate progress toward America’s climate goals and lower electricity costs for people across the country.

Provide Direct Pay of Tax Credits

Direct pay is a fiscal mechanism that would allow utilities to receive cash payments from the government for the value of the tax credits earned by an asset (or that would be earned if the asset owner were a taxpayer), without regard for current tax capacity.

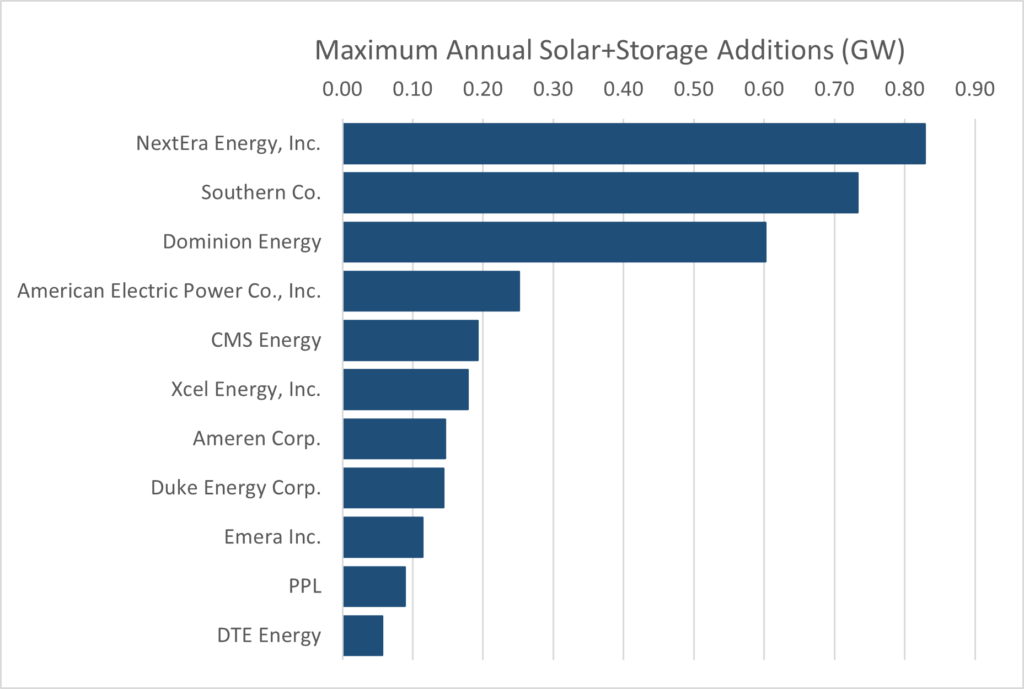

Under existing law, companies realize a cash benefit from the ITC and PTC only if, absent the credits, they would have taxes to pay in that year. Otherwise, the credits must be carried forward for possible future use. RMI analysis of financial disclosures shows that in 2019, US IOUs together had combined tax liabilities sufficient to build less than 4 GW of new solar and storage per year—enough capacity to replace just one or two coal plants.

The reason IOUs pay so little in taxes is that, over the past two decades, policymakers have put in place “bonus depreciation” provisions that incentivize investment to fight recessions. These provisions allow companies to immediately deduct as an expense some or all of the investment they make in new capital assets from their income for calculating their taxes in that year. As a result, growing utilities that are building assets have reported large net losses for tax purposes that are likely to offset any taxable earnings they may have for many years to come.

Utilities therefore often do not owe enough in taxes to see an immediate cash benefit from the existing ITC and PTC. This adverse cash flow impact can negatively affect the company’s credit and in turn harm its shareholders. Depending on state regulatory practices, the inability of a utility to use tax benefits efficiently may instead result in its customers realizing significantly reduced value from tax incentives. Either way, the policy intention of the credits—to lower the cost of clean energy—is undercut.

Exhibit 1. Regulated investor-owned utilities together held enough federal tax liability in 2019 to build 4GW of solar + storage. We exclude Berkshire Hathaway Energy from this analysis, because it is unique among utility holding companies in having a parent company with significant federal tax liabilities to take advantage of the ITC and PTC. Source: FERC Form 1, RMI analysis.

A utility could instead purchase clean power from a third-party developer or partner with a tax equity investor—a large financial or corporate institution that has found a market selling its tax liability to renewables developers—to realize the benefits from tax incentives for their customers. However, third-party ownership and tax equity often come with higher financing costs that reduce the amount of tax incentive benefits that can be passed on to customers. Further, these arrangements are at odds with the utility’s core business model, which is to deploy capital over time.

Public power agencies and many cooperative utilities are in a similar situation for different reasons. As not-for-profit entities, these utilities cannot directly use the tax benefits at all. Instead, these utilities must rely on private-sector developers and investors who can claim the tax credits to finance clean energy. As private entities, they have capital costs much greater than the government debt that not-for-profit utilities would otherwise use to finance fossil energy resources. This capital cost penalty significantly reduces or even eliminates the relative cost benefit from clean energy subsidized through tax incentives. As a result, the not-for-profit utilities that serve more than 25 percent of US customers see a much lower economic benefit from switching to clean energy than even a comparable for-profit utility (with or without tax capacity).

Direct pay would eliminate these disparities. And it would significantly improve the ability of public power, cooperative, and investor-owned utilities—which together are responsible for 80 percent of power-sector emissions from coal—to deliver cost savings to their customers from transitioning to cheap, carbon-free electricity.