Russia is Heating Up—Cutting Methane from Oil and Gas is the Cure

Few have heard of Taymyr, a northern Russian province located at the mouth of the Arctic Ocean. Here, land temperatures have already hurdled past a perilous point by about 4.5°C since 1960.

Despite these alarming numbers, Taymyr is also where Russia is planning to build fifteen new towns, a pair of airports, thousands of kilometers of pipelines and electrical lines, and a seaport to sail a fleet of top ice-class tankers. The goal is for Vostok Oil is to export millions of tons of northern Ural tundra oil.

The project is being heralded as an economic triumph for Russia. Vostok was established as the Arctic division of the major Russian energy company Rosneft, which just sold a portion of its stake in this multi-billion-dollar project to a consortium including Vitol, the Dutch energy and commodity trading firm. India is also a big investor in the venture.

This raises eyebrows. Despite the recent methane pledge signed by the EU and over 40 other countries, such projects could push the global climate over the edge. Methane leakage from oil and gas systems heat the planet over 80 times more than CO2. And such warming in the Arctic region heightens risks of melting permafrost, which releases even more methane setting off a vicious cycle.

In fact, earlier this week, the Washington Post published an in-depth story on the climate risks posed by the invisible nature of methane emissions, especially for countries like Russia that ignore them. And President Putin just announced that he is not planning to attend the upcoming annual climate conference in Scotland.

Russia is now claiming it will be “carbon neutral” by 2060 on account of its vast forests absorbing carbon. This calls into question whether Russia can be trusted to safely govern its climate impacts that could devastate Arctic northern ecosystems. In fact, the very notion of building and operating a major oil and gas mega project in such a fragile environment is highly questionable. Instead, financing for projects that pose an immediate danger to planetary balance should come under greater scrutiny, so potential investors—Western nations, trading houses, and other backers—understand that developing this region’s oil and gas supplies poses inordinately high climate risks.

Holding countries, companies, and financiers accountable for their environmental impact requires that we have greater visibility into methane emissions at a variety of levels—from advanced models to satellites. Such tools deliver a clear picture of methane emissions at varying levels of granularity. Together with transparency, effective climate decision-making depends on greater climate intelligence because we cannot manage what we do not know.

Revealing Emissions and Reporting Shortcomings at the Country Level

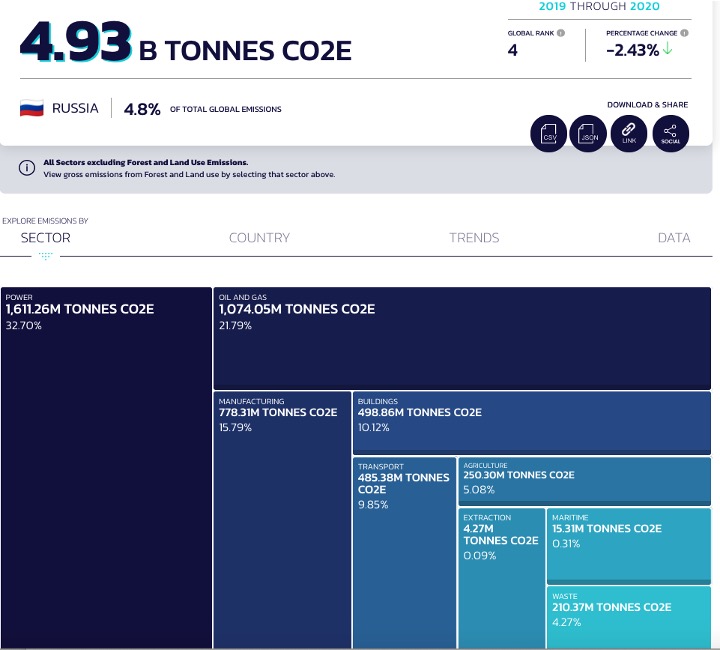

Launched in September, Climate TRACE is the world’s first comprehensive accounting of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions based primarily on direct, independent observation by satellites, remote sensing, and advanced analytics. TRACE data evaluates the size and scale of Russia’s emissions in the oil and gas sector and what this means for climate change. Russia is the fourth largest global greenhouse gas emitter, and the oil and gas sector is the second largest source of GHG emissions after power. (And Russia’s GHGs ranking is due to rise if it eventually produces 2 million barrels of oil per day In Taymyr.) Today, the country is among the 15 top production countries and 15 top refining countries that account for the lion’s share of oil and gas sector emissions.

Alongside the US, Russia is in the category of countries that pollute doubly––emitting massive amounts of GHGs from both oil and gas production and refining.

Source: https://www.climatetrace.org/

TRACE fills the gaps in self-reporting that—as the Washington Post pointed out—has allowed countries to undercount emissions. Among the world’s top countries that submit regular GHG inventories, including Russia, emissions from oil and gas production and refining may collectively be around double the amount in recent UNFCCC reports.

Digging deeper into Russia’s oil and gas sector reveals the magnitude of the climate threat. For Climate TRACE, RMI modeled both the methane and carbon dioxide intensity of a majority of oil and gas assets worldwide. This is important because no two barrels of oil or cubic feet of gas are equal in their climate footprint. In fact, emissions vary widely based on where, when, and how they are extracted, processed, and transported.

It turns out that Russia has one of the largest climate footprints of any country globally in the methane and CO2 intensity of its oil and gas production.

Leveraging Emissions Transparency to Guide Action

Having this powerful information is only part of the puzzle. This climate intelligence needs to be used to prioritize action and activate markets if we are to limit the Earth’s warming to 1.5oC in this decisive decade.

The number one target—in Russia and elsewhere—that too few are talking about but that offers a ripe opportunity for immediate reduction are ultra-emitters.

Ultra-emitters are characterized by sporadic releases of huge amounts of methane from aging infrastructure, maintenance operations, and equipment failures that are not accounted for in current emissions inventories. They are primarily detected over the largest oil and gas basins in the world, but are relatively large and common in Russia as shown in the figure below.

Global map of the ~1,200 oil and gas detections from TROPOMI from 2019–2020

Image Credit: Carbon Mapper

According to Carbon Mapper, methane ultra-emitters could bump up oil and gas emissions 10 percent or more. Carbon Mapper is adding to the global monitoring capabilities of existing satellite constellations with two satellites launching in 2023, plus expanded monitoring by aircraft. These satellites will pinpoint ultra-emitters. And, once spotted, they represent the lowest hanging fruit for immediate reductions.

Informing Climate-Differentiated Markets

Should Western Europe be importing gas from Russia? Is it clean enough to meet the standards set out under the new Methane Pledge that aims to reduce emissions by 30 percent by 2030? The answer depends on the performance standards established to implement the pledge.

To address this concern, we have created a new low-methane gas standard, MiQ. This open-source standard transparently differentiates GHGs from physical assets like wells, refineries, and pipelines. MiQ is an example of an independent certification that grades natural gas based on its methane emissions, industry practices, and monitoring techniques. RMI is in the process of certifying methane emissions from 10 percent of all US oil and gas, and is expecting increased pick up by oil and gas companies that operate globally—ultimately aligning markets to support the Global Methane Pledge.

Oil and gas investors and customers should be accountable to the emissions that they are bankrolling. This is evident in the case of Vostok in Taymyr. As we head into COP26, with climate intelligence in hand, governments, investors, courts, activists, and consumers will be empowered to activate climate-aligned markets.

Deborah Gordon’s new book, No Standard Oil: Managing Abundant Petroleum in a Warming World, (Oxford University Press) is due out later this month.