Are Residential Demand Charges The Next Big Thing in Electricity Rate Design?

Guest author Matt Lehrman is an RMI alum.

Demand charges for commercial and industrial customers have long been a part of the electric industry. Since utilities need to build infrastructure to meet both instantaneous and long-term requirements, the utility bill contains both an energy charge, which measures the amount of electricity a customer uses over time, and a demand charge, which measures how much power is used at any given point in time.

However, residential customers are rarely subject to a bill with a demand charge. This is because, until recently, residential electricity loads were pretty much the same from one customer to the next. We all (more or less) woke up, took a shower, went to work, came home, turned on the lights, cooked dinner, watched TV, did a load of laundry, went to bed. With each customer in the residential class looking an awful lot like the next, utilities and regulators could lump energy and demand elements together into one $/kWh price.

But today, this assumption is no longer true. All residential customers are not the same. We now have access to LED lights, smart thermostats, plug-in electric vehicles, rooftop solar, demand-flexible water heaters, battery energy storage, and myriad other technologies that make our respective loads and our consumption patterns potentially very different. Critically, it is now inexpensive to meter these differences, including time of use and the magnitude of the demand. Separating out demand charges may be a good way to promote more fairer cost allocation among ratepayers, while also motivating customers to reduce strain on the system. More than a dozen utility companies across the country have implemented or are currently considering residential demand charges.

WHAT IS A DEMAND CHARGE?

A demand charge is based on the maximum amount of energy a customer uses at any one instance over the course of a billing cycle. It reflects the cost that a utility incurs to maintain the infrastructure to deliver what the customer wants, when the customer wants it. Think of it as the “size of the pipe” (figuratively) that delivers electricity to customers—a bigger pipe costs more, but can deliver more juice at any instant.

The distinction between how much electricity you need right now and how much you need in total over time is important. Imagine you want to fill a swimming pool with water. You could fill it in minutes with a fire hose. Or you could fill it in hours with a trickle from a garden hose. In both cases, you get the same amount of water. But how much water you get how fast is quite different, and that difference incurs costs to the system.

Historically, this has only been important for large customers that require high amounts of power throughout the day. But as the penetration of distributed energy resources from rooftop solar PV to electric vehicle charging to programmable, controllable thermostats to stationary storage grows, the demand charge can be both a promising solution to the puzzle of how to more equitably collect grid infrastructure costs as well as a price signal that encourages efficiency, load shifting and peak management, and the diverse array of DER product combinations that can perform these tasks.

Consider two hypothetical residential customers, both with the same monthly kWh usage:

- Customer A has no DERs and uses approximately the same number of kWhs each day. The customer works at home and has a consistent demand throughout the day.

- Customer B has rooftop solar and an electric vehicle. The rooftop solar ramps up production just as Customer B shuts off lights and appliances and leaves for work, seriously depressing that home’s net demand on the grid (and even likely exporting surplus solar PV). Solar production later decreases in the afternoon just as Customer B gets home, turns on the same lights and appliances, and plugs in an electric vehicle, greatly increasing the home’s net grid demand.

At the end of the month, the kWh usage is the same, but the peak demand and benefits and costs to the grid of each customer are very different. Yet both pay the same $/kWh energy charge. In this example, a demand charge would more equitably charge each customer for the service required from the grid closer to each customer’s true cost of service. The customer with a “traditional” and smoother load curve would cause fewer system costs, while the customer whose net grid demand surges from essentially zero to peak would cause greater costs for grid resources (generation, transmission, distribution) to meet that surging need.

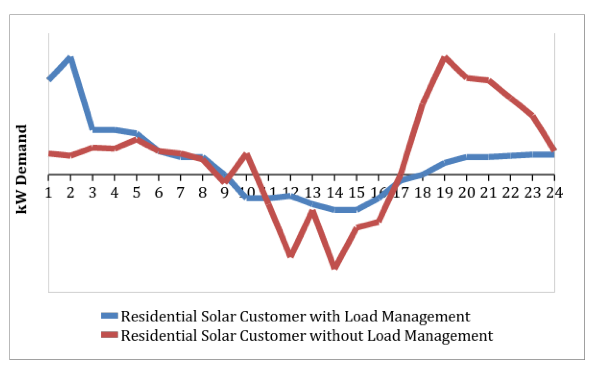

Source: Adapted from SDG&E

The above chart shows two similar customers each with rooftop solar, air conditioning, and a pool pump. The blue line shows one customer using timers and other load controls to align consumption with solar output and away from peak periods (assuming demand charges vary by peak and off-peak periods). The red line shows a customer with unmanaged load. While the overall peak demand is comparable, a demand charge with peak and off-peak rates would charge the blue customer much less (with demand shifted to off-peak hours) than the red customer (with demand coincident with peak hours).

Thus, the demand charge accomplishes two important goals as DERs proliferate:

- Promoting customer equity: The demand charge bills customers based on the demand the customer places on the grid. This helps differentiate between a customer with a 2 kW solar PV array and an electric vehicle and a customer with a 10 kW array with load that does not align with the solar output.

- Providing a price signal for DERs to provide value on both sides of the meter: A demand charge creates a price signal for customers to smooth load. Whether the customer does this through efficiency, battery storage, or automation of EV charge management, this creates both short- and long-term benefits—monthly bill savings in the short-term (through reduced demand charges) and the deferral or elimination of new infrastructure investments to meet growing peak demand (stabilizing rates over the long-term).

DEMAND CHARGES CAN ALIGN DER INCENTIVES WITH SYSTEM BENEFITS

Demand charges can also help to address one of the most vexing debates between utilities, regulators, DER providers, and customers—how to properly charge and compensate distributed generation (DG) customers. Proposals to increase fixed charges or to offer value of solar tariffs remain controversial; there is little agreement on an appropriate value of solar calculation and on which charges are fixed and which charges are variable. This uncertainty creates an unclear value proposition for DG customers, making financing more difficult (and expensive) and constraining the growth of DERs. So while demand charges could be good for all residential customers, they’re especially suited to customers with DERs.

Two utilities recently added demand charges for DG customers. While these charges might slow adoption of solar, or may be too drastic a change all at once, they could potentially unleash new combinations of DERs to help customers better manage the demand, which can bring value to the entire system.

- Salt River Project (SRP) added a seasonal, inclining block demand charge to future net-metered PV customers. One reason for this was to create an incentive for customers to install west-facing PV systems, so that generation better aligns with system peak. SRP also states the demand charge will help customers adopt new technology (e.g., load controllers, smart thermostats, or battery technology), and change their behavior to respond to those price signals.

- In its March 2015 general rate case filing, Westar Energy proposed a choice for residential DG customers. One of the two options entailed a lower fixed customer charge plus a demand charge.

Demand charges can be beneficial for customers without solar as well. At least 14 utilities have implemented demand charge rate options for residential customers with or without solar. For example:

- In South Dakota and Wyoming, Black Hills Power offers a demand charge option for all residential customers. To help customers manage their electricity demand, maximize operational benefits to the grid, and minimize their monthly bills, the company promotes a Demand Controller Program. The program connects load control devices to heating and cooling systems, hot water heaters, clothes dryers, and hot tubs to cycle these appliances on and off in 15-minute cycles to help customers manage demand charges. The controller is owned and operated by the customer instead of the utility, leaving ultimate decision making over appliance control to the customer.

CONCLUSION

Demand charges are a promising step in the direction of more sophisticated rate structures that incent optimal deployment and grid integration of customer-sited DERs. A demand charge more equitably charges customers for their impact on the grid, can reward DG customers with bill savings, and opens up potential for an improved customer experience using load management tools. It can also benefit all customers through reduced infrastructure investment and better integration of renewable, distributed generation.

Image courtesy of Shutterstock.com