Minigrids in the Money

Six Ways to Reduce Minigrid Costs by 60%

In sub-Saharan Africa, hundreds of millions of people (about 65 percent of the population) live in communities that lack access to electricity. As a key enabler of economic development, the lack of energy access stymies broader efforts to grow local wealth and improve quality of life. Understandably, to address this need, African governments, development partners, and others are working tirelessly to increase energy access on the continent.

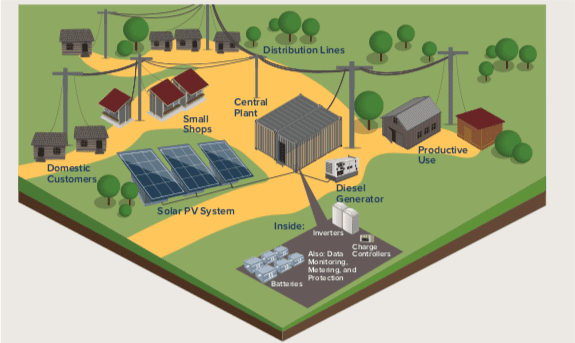

Governments’ traditional method of extending the central grid to provide electricity connections in remote communities has not worked well in Africa due to a slew of complicating factors, including low end-use consumption and the high cost of grid extension. But a promising array of alternative models for providing light and power is becoming available. Millions of solar lanterns and small off-grid solar home systems are now providing light, electricity, and heat to families in rural areas across the continent. While these off-grid solutions provide a valuable service, the need in hundreds of thousands of African towns extends beyond the lighting, phone charging, and small appliances that can be powered by smaller off-grid systems; they also need larger-scale solutions that can power cassava milling, oil pressing, cold storage, small manufacturing, and other activities that drive economic growth.

A new Rocky Mountain Institute report, Minigrids in the Money: Six Ways to Reduce Minigrid Costs by 60% for Rural Electrification, describes the barriers that minigrids currently face in reaching this potential and lays out a prospective pathway to address them and to bring minigrids to scale. The promise of minigrids is illustrated by looking at two typical and neighboring off-grid communities in central Nigeria.

A tale of two towns

Off Highway A-2, down dirt roads grooved by the tires of trucks and vans crowded with produce, lies Ishau, an off-grid community tucked between Niger and Kaduna States. This lively town provides an example of the energy needs and challenges in rural economies. A businessman in the community, pictured below, pays $0.63 per kWh to run two large, 12 kW diesel-driven grain-milling machines. His is one of eight large milling businesses in the community, along with welders, barbers, carpenters, and a small guild of 30 tailors eager to transition away from pedal-powered sewing machines. Each of these businesses buys expensive diesel or petrol to power small appliances or uses hand saws or foot pedals. Many of the business owners long for affordable, convenient, and reliable electricity.

In contrast stands Tungan Jika, eight hours to the west along equally well-worn roads, where a minigrid owned and operated by Nayo Tropical Technology, and partially funded by a grant, has been providing power for the community since March 2018. Here, 80 local businesses benefit from a 100 kW peak solar-diesel-battery hybrid system. During the day, refrigerators hum, grain mills rattle, and welders’ tools crack and pop. As night falls, lights illuminate the doors and windows of many of the over 700 households in the community as people turn on their appliances that help improve quality-of-life—such as fans, radios, and TVs. Businesses and residents pay a tariff of about $0.40/kWh for reliable, 24-hour power.

Cost reductions to drive scale

Off-grid economies like Ishau are common across sub-Saharan Africa and large swathes of Southern Asia. The International Energy Agency estimates a global investment of $113–$190 billion is needed for minigrids alone by 2030. Despite that potential, significant market barriers currently limit the minigrid market to individual projects like Tungan Jika.

Minigrids in the Money highlights four key barriers to using minigrids to achieve widespread rural electrification:

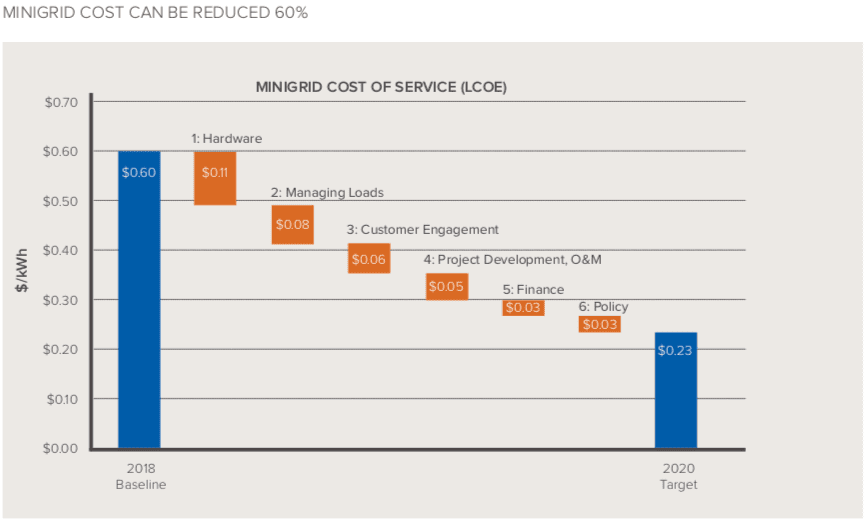

1. Most minigrids are still too expensive. Although several companies are now developing standardized designs, most current minigrids are unique, custom installations with a typical levelized cost of energy (LCOE) of well over $0.60 per kWh.

2. Minigrid-produced power is underutilized. The typical rural customer lacks the resources to buy water pumps, small grain mills, refrigerators, and other devices and appliances that would put to use more of a minigrid’s potential electricity generation and improve capacity utilization, making more efficient use of assets.

3. Financing is expensive or unavailable. Minigrid companies have struggled to secure affordable financing, keeping them from scaling their operations.

4. Regulatory and policy barriers slow progress and increase costs. Slow, unclear, or unpredictable licensing and tariffs, as well as requirements that limit the prices that can be charged for electricity, add further risk and make beneficial partnerships more difficult.

Given these barriers, the report identifies a pathway to reduce minigrid costs by 60 percent. Following this pathway would rapidly accelerate market growth for minigrids by cutting the LCOE of minigrid-produced power from between $0.60 per kWh and $1.00 per kWh today, to $0.25 per kWh by 2020.

The steps along the pathway are:

1. Reduce costs of minigrid hardware. Leverage the ongoing fall in hardware costs by bulk purchasing components and streamlining procurement. Develop standardized, modular designs and simplify construction methods.

2. Ensure that the electricity generated is fully utilized through demand stimulation and optimized load management. Focus on the productive use of energy by prioritizing areas with existing productive use business or stimulating productive demand, with an emphasis on low-cost renewables.

3. Focus on customer acquisition and relationship management. Engage the community and local groups to sign up customers, inform them of opportunities, and retain their business.

4. Cut costs of constructing and operating minigrids. Increase efficiency by clustering minigrids, taking advantage of remote monitoring technology, and utilizing local labor.

5. Enable low-cost financing. Increase the availability and reduce the cost of capital for minigrid projects by standardizing financing, use grant funding to provide for informative pilots, clarify proof points early, and provide consumer financing for appliances and productive use.

6. Reduce regulatory barriers, costs, and risks. Create transparency and an enabling environment for minigrids by setting clear and well-crafted regulations, fair and stable taxation and customs regimes, and clear policies around grid extension.

Providing energy access and low-cost power for productive uses to the many communities across sub-Saharan Africa like Ishau is core to powering rural economies and creating a foundation for economic development. Minigrids are a key tool to do this, but first industry, governments, minigrid companies, and development partners must work together to remove the barriers in the way. Through cost reductions, minigrids can quickly scale as a commercially viable business model to provide access to millions of people and businesses across the world.

Download Minigrids in the Money: Six Ways to Reduce Minigrid Costs by 60% for Rural Electrification