The historic architecture of the Boston Harbor and Financial District at night.

Massachusetts’ Governor Must Act to Secure Clean, Affordable Buildings

Late last week, Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker vetoed S.2995, a landmark climate action bill that would have created strong measures to achieve the state’s legislated carbon emissions reduction targets and the Governor’s own climate commitments. In his letter to the legislature, Baker pointed to the bill’s inclusion of a net-zero stretch code as a central reason for his veto, citing concerns about economic impact on affordable and market rate building development. This is contrary to developments on the ground, research from Rocky Mountain Institute, and the research published by his own Executive Office of Energy Affairs (EEA) in December 2020.

A stretch code is a voluntary, new construction building code with higher efficiency standards than the base building code that would allow communities to adopt more stringent local building standards. The proposed stretch code calls for net-zero buildings: highly efficient buildings that get or offset all of their energy from renewable sources and typically include electrified space heating and hot water to eliminate onsite emissions from fuel combustion. Massachusetts’ own analysis clearly states that eliminating building emissions is required to meet the state’s target of net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. Enacting a net-zero code as soon as possible is a critical strategy to achieve this goal.

There’s no need to wait. All-electric, single-family new construction is a good economic proposition for consumers today. Affordable housing developers are out front on all-electric new construction because they find that building without gas is a better long-term investment and can be financed at a lower cost. Ultimately, continuing to invest in repairing and expanding a rapidly degrading gas infrastructure to fuel new homes is not aligned with legislated climate targets, nor is it a wise financial decision. A net-zero stretch code that promotes electrification, like the one proposed in S.2995, is the right way forward for Massachusetts communities and residents.

State Analysis Points to Electrification

Massachusetts state agencies have studied the best way to meet climate targets in the timeframe required and their recent publications conclude that the Commonwealth needs to eliminate fossil fuels from buildings. The commonwealth’s 2030 Clean Energy and Climate Plan identifies energy efficiency and electrification as the most cost-effective and technologically feasible approaches to achieving emissions reductions.

Similarly, the recently released 2050 Decarbonization Roadmap illustrates the need for electrification of residential and commercial space heating. According to the roadmap, new construction offers the easiest and most economically attractive way to start decarbonizing the building sector. A net-zero building code is the most effective way to immediately electrify new buildings and to halt the addition of new gas-burning equipment and gas infrastructure.

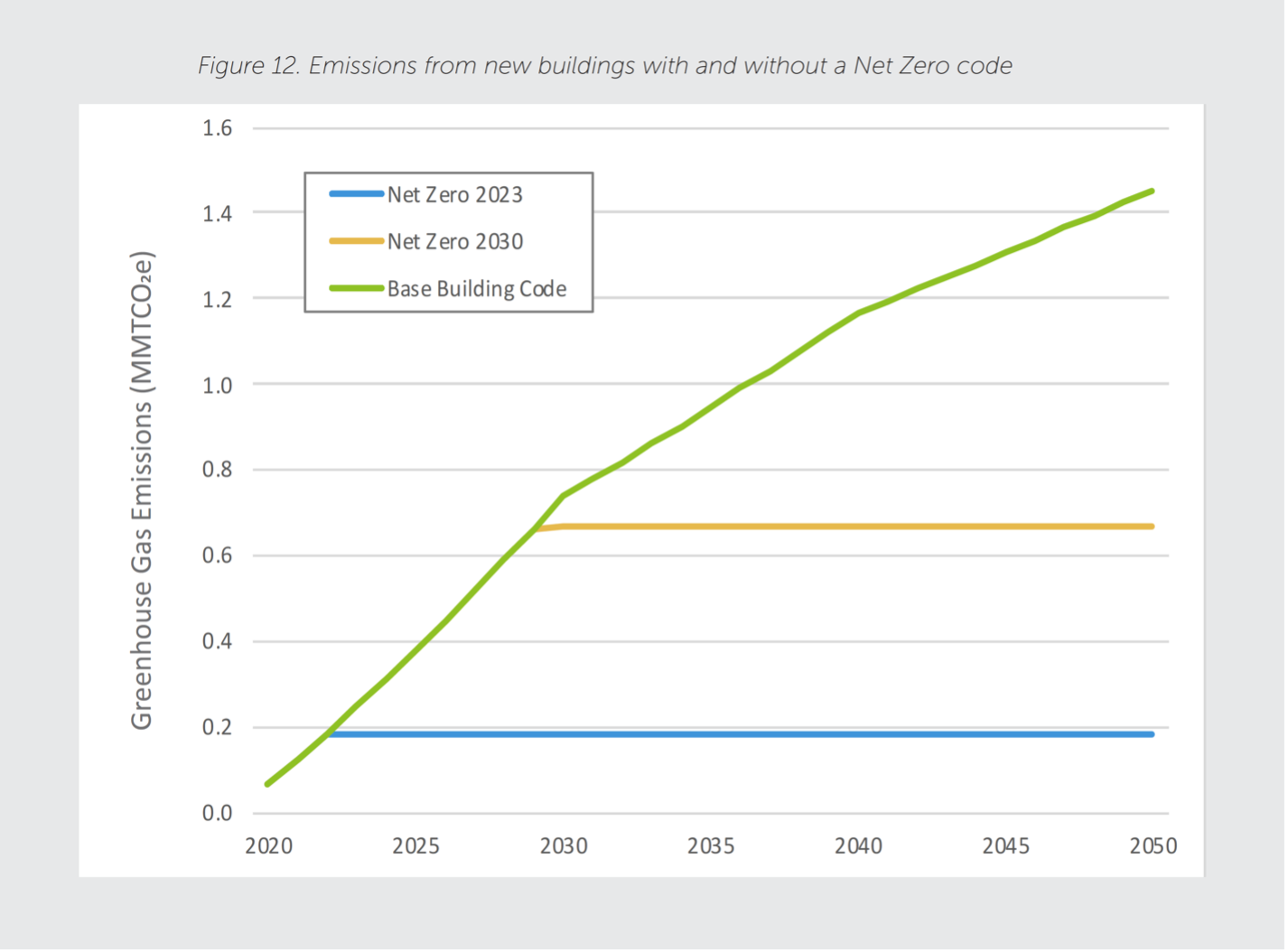

The 2050 roadmap also concludes that the sooner the state can adopt a mandatory net-zero building code, the better. This is an even more stringent requirement than the net-zero code provisions in bill S.2995, which call for an optional stretch code. The roadmap shows carbon emissions from new buildings growing seven-fold by 2050 with the current base building code as compared to enacting a statewide, mandatory net-zero code starting in 2023. Waiting also has a climate cost—emissions from new buildings would triple if a net-zero code is delayed to a 2030 start date.

Net-Zero Affordable Housing Is Already Here

Contrary to concerns raised by real estate groups and Baker, the adoption of a net-zero energy stretch code will not imperil production of affordable housing. In fact, there are numerous examples of net-zero affordable housing projects in Massachusetts today.

370 Harvard Street in Brookline is a sustainable, 62-unit building with 57 affordable units currently under construction. Finch Cambridge, a 98-unit affordable housing project completed in summer 2020, includes a high-performance building envelope that is expected to achieve over 40 percent more energy efficiency than even the toughest building codes.

Beyond helping communities and the state meet climate targets, net-zero buildings provide several added benefits. For developers, high performance, net-zero energy buildings can secure lower interest rate loans, which provides favorable economics for the projects. For affordable housing residents, net-zero buildings provide access to modern systems and safer indoor air.

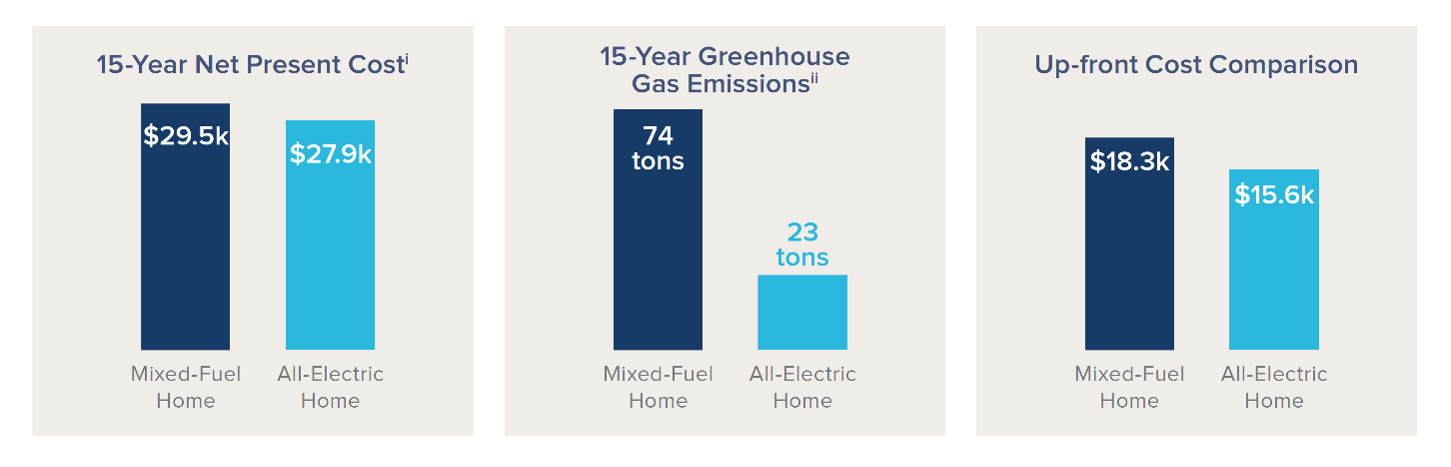

All-Electric New Homes Save Money Now

While Baker referenced the concerns of stakeholders regarding increased cost and uncertainty associated with a new stretch code, recent RMI research shows this is not the case. Building a new, all-electric, single-family home in Boston is already cheaper than building with gas and saves residents $1,600 over a 15-year period when including utility costs. Massachusetts’ 2030 Clean Energy and Climate Plan echoes this conclusion, finding that almost all new buildings can pursue an efficient electric design that increases occupant comfort and pays for itself by reducing heating equipment cost and energy requirements.

A high-performance stretch code that promotes electrification, like the one proposed in S.2995, will send a strong market signal to home builders, HVAC installers, and equipment manufacturers, providing common standards across Massachusetts and surety of an expanding customer base. Lifetime savings are only expected to increase as upfront costs for heat pump space and water heaters continue to fall with more installations across the Commonwealth.

Maintaining Gas Infrastructure Is Costly

Critics of S.2995’s stretch code overlook the significant costs of maintaining the status quo—continuing to build out and operate gas infrastructure across the Commonwealth. Massachusetts has some of the oldest and most leak-prone gas pipelines in the country. Applied Economics Clinic estimates that it would take over 90 years to fully pay off the $15.5 to $16.6 billion required to repair the state’s gas pipeline infrastructure.

These long-term gas infrastructure costs have been disguised by lower gas supply costs in the past, but if we continue to build out gas infrastructure these costs will continue to accrue and grow. Gas utility customers are ultimately the ones who will bear the cost of these infrastructure investments. It would be imprudent to continue compounding the problem by extending the gas system to new buildings. The ongoing Massachusetts Department of Public Utilities investigation into long-term gas planning only highlights the urgency of new policies and structures that transition the Commonwealth, and its ratepayers, away from reliance on gas.

State Must Encourage, Not Impede, Communities’ Climate Leadership

Following the July 2020 decision from the Massachusetts Attorney General’s Office that local policies that mandate electrification in new construction are preempted by state building codes, municipalities have sought alternative pathways to lead the way on the next generation of clean, affordable buildings. As part of the MA Building Electrification Accelerator program co-led by RMI and local campaign organizers, over 15 communities have already been working to advance individual new construction electrification policies through home rule petitions and zoning incentives.

A net-zero stretch code would allow communities to voluntarily adopt local building policies in a simpler way that does not conflict with state law. Additionally, such a common code would provide the strong market signal needed to rapidly accelerate adoption of electric buildings.

It is clear that the development of new buildings that use gas for heating, hot water, and cooking must stop. Burning fossil fuels in buildings already accounts for almost a third of the state’s total carbon emissions and these fuels are a threat to residents’ safety and health. There is no time to waste in accelerating the transition to a new era of modern, efficient buildings that operate free from fossil fuels. Massachusetts needs strong statewide leadership and a clear policy direction to make this happen.