two adjustable wrenches tightening up tee-fitting on 15 mm copper pipework with loose pipe in background on white gloss surface

Fossil Gas Has No Future in Low-Carbon Buildings

States and cities across the country are beginning to grapple with a persistent source of carbon emissions that has largely gone ignored: burning fossil fuels in buildings. While the electric power sector nationally has reduced emissions more than 25 percent, there has been no change in carbon emissions from direct fossil fuel use in homes and businesses in decades.

While far more attention has been paid to reducing emissions in the transportation and electricity sectors, local leaders are realizing they need to slash direct building emissions to have any hope of meeting their climate goals. Over 20 California cities took steps to phase out fossil fuels in buildings this year, along with Brookline, Massachusetts. Cities in a handful of other states may follow suit next year.

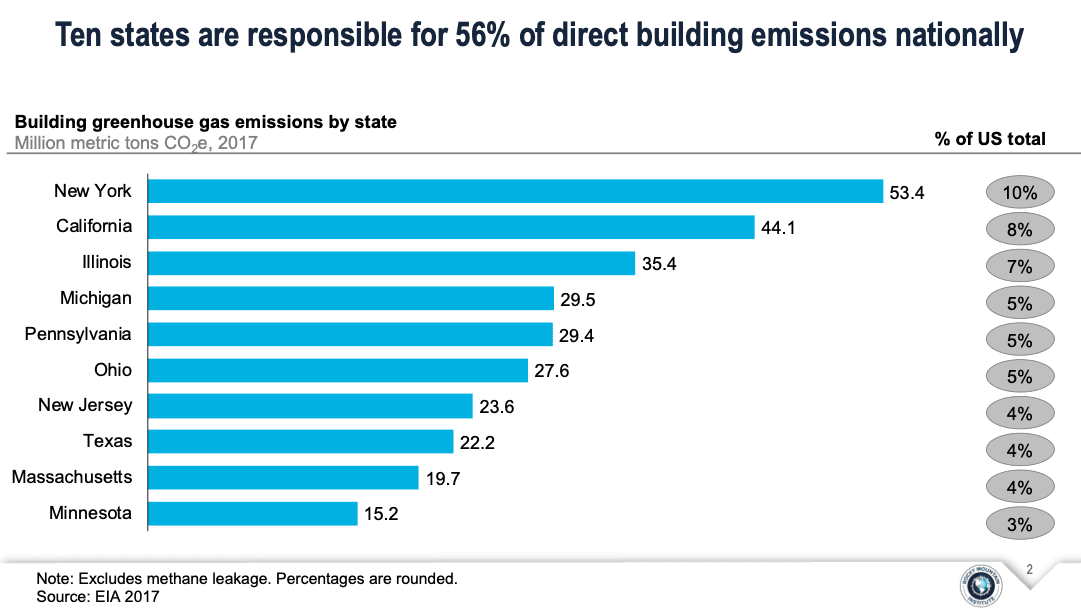

Burning gas along with smaller amounts of oil and propane in buildings accounts for 10 percent of total US economy-wide emissions, and only 10 large states are responsible for 56 percent of those emissions.

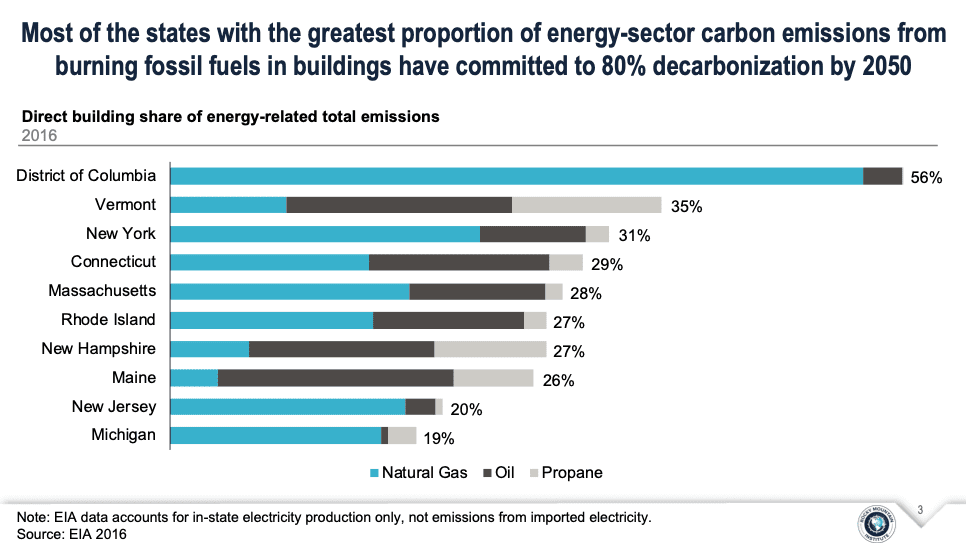

But, as RMI’s new analysis, The Impact of Fossil Fuels in Buildings, shows, the proportion is much higher in several states. And these states with the highest proportion emissions from fossil fuels in buildings all have ambitious climate goals, committing to as much as an 80 percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. Achieving these state-level commitments is necessary for the United States to maintain pace toward meeting Paris climate targets—irrespective of federal action.

Although these figures do not account for the emissions impact of imported electricity, combustion emissions produced within these jurisdictions suggest it will not be possible to meet climate goals without immediate and durable action on building fossil fuel use. Including building-sector emissions from electricity only ramps up needed ambition for building decarbonization through efficiency, electrification, and renewable electricity supply.

Of the top 10 states and territories by total proportion of energy sector emissions from building fossil fuel use, Connecticut, Washington, D.C., Maine, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, and Vermont have each set climate targets that cannot be achieved without removing fossil fuels from buildings.

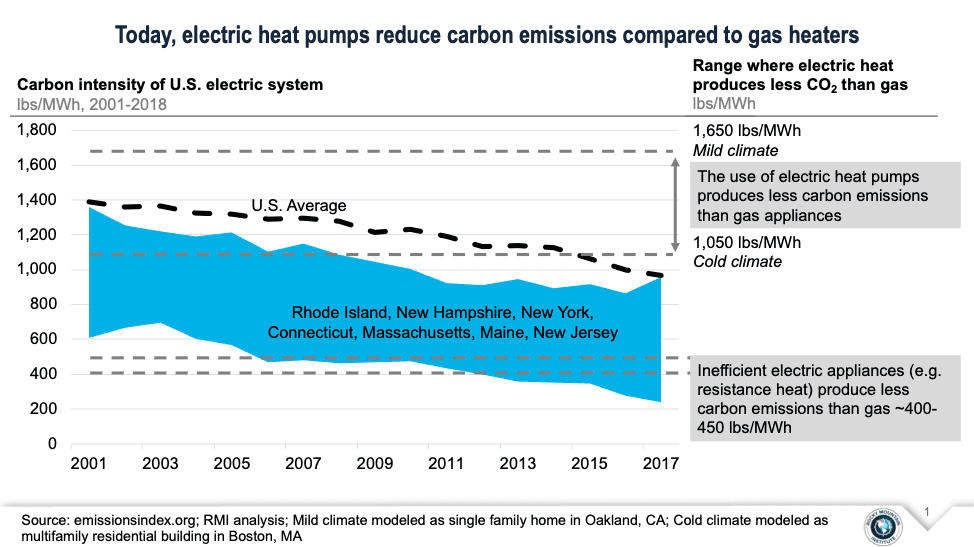

Today, in each of these climate-ambitious states, electrifying air heating and cooling with air-source heat pumps will immediately reduce emissions when compared to gas, oil, and propane alternatives– even in the coldest, most heating-intensive climates. In addition, all of these states still need to reduce gas consumption in existing buildings.

An astute reader will notice many of these states are in the Northeast, where there have been many notable state efforts to switch customers off of expensive and polluting heating oil and propane. And while we agree it is critical to get these customers off of these fuels as fast as possible, our analysis demonstrates the importance of leapfrogging a reliance on oil and propane to electric, rather than to gas.

It is not possible to meet any of these states’ climate goals by switching existing fuel oil and propane customers to gas alone. Switching from fuel oil to gas may only reduce a home or business’s emissions by as much as 27 percent, or around 16 percent for propane.

Therefore, the billions of dollars that these states are collectively spending on expanding and repairing gas infrastructure is simply incompatible with their climate goals. These billions of dollars assume customers will continue to pay for this infrastructure well past 2050, a time at which all fossil fuel consumption in most states must approach zero.

The good news is that several states have started to enact policies that will accelerate the transition to all-electric homes and buildings. But if these states are serious about meeting their carbon targets, more effort is needed. Even if all new building construction is zero-carbon, and all existing fuel oil and propane customers switch to zero-emission alternatives, a significant effort still must be made to switch the remaining homes and businesses—those consuming natural gas today—to a zero-carbon source.

Let’s see how this scenario breaks down for each jurisdiction.

District of Columbia

Overview: Washington, D.C. has the country’s highest proportion of energy-sector carbon emissions from burning fossil fuels in buildings, nearly all of which come from burning gas. At the same time, D.C. is committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions 50 percent (below 2006 levels) by 2032 and 80 percent by 2050.

Building emissions target (reductions): 80 percent (residential), 76 percent (commercial) by 2050

Average number of buildings that must be decarbonized to meet state targets: 4,000 homes, 250 commercial buildings per year to 2050

Natural gas expansion (in 2017): 2,500 homes, 30 commercial buildings

Vermont

Overview: More than one-third of Vermont’s total energy-sector carbon emissions come from burning fossil fuels in homes and businesses. Vermont was also one of the first states in the country to set a goal for reducing carbon emissions. In 2016, the state established new goals of achieving a 40 percent reduction in carbon emissions (based on 1990 levels) by 2030 and an 80 percent to 90 percent reduction by 2050.

Building emissions target (reductions): convert all oil and propane buildings to zero-carbon, reduce commercial gas use 33 percent

Impact of switching fuel oil and propane customers to gas: building emission reductions target increases to 74-82 percent reductions by 2050

Average number of buildings that must be decarbonized to meet state targets: (if all fuel oil and propane customers switch to gas): 313 commercial, 6,198 residential customers per year to 2050

Natural gas expansion (in 2017): 1,000 new residential customers, 200 commercial buildings

New York

Overview: New York consumes more gas in its buildings than any other state. It’s also the top state in terms of direct building emissions, contributing 10 percent of the nation’s total. New York’s State Energy Plan set some of the most ambitious climate targets in the country, aiming to reach the following milestones by 2030: 40 percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from 1990 levels; 50 percent of energy generation from renewable energy sources; and 23 percent decrease in energy consumption in buildings from 2012 levels.

Average number of buildings that must be decarbonized to meet state targets: 1,600 commercial buildings, 67,000 residential units over 10 years (7-8 zero-carbon retrofits every hour until 2030)

Natural gas expansion (in 2017): 34,000 new homes and businesses added to the gas system in 2017

Recently, New York State set the bar even higher: the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act seeks to reduce greenhouse gas emissions 85 percent by 2050 while achieving net-zero emissions.

Connecticut

Overview: Nearly one-third of Connecticut’s total energy-related emissions come from burning fossil fuels in buildings. The state has a carbon emissions reduction target of at least 45 percent (below 2001 levels) by 2030. Earlier this year, the governor signed an executive order directing the state to analyze pathways to achieving zero-carbon electricity by 2040.

Building emissions target (reductions): convert all propane and fuel oil buildings to zero carbon, reduce commercial sector emissions 17 percent by 2030

Impact of switching fuel oil and propane customers to gas: building emission reductions increased to 35 percent commercial reduction and 16 percent residential

Average number of buildings that must be decarbonized to meet state targets: 1,009 commercial gas customers each year to 2030, or if oil and propane customers switch to gas, 2,601 commercial buildings and 18,443 residential units per year

Natural gas expansion (in 2017): 7,092 homes and 435 businesses

Massachusetts

Overview: Almost one-third of Massachusetts’s total energy-related emissions are the result of burning fossil fuels in buildings– primarily gas. In 2008, Massachusetts law set economy-wide greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reduction goals for the state, aiming to achieve reductions between 10 percent and 25 percent below statewide 1990 GHG emission levels by 2020, and 80 percent below statewide 1990 GHG emission levels by 2050.

Building emissions target (reductions): convert all fuel oil and propane customers to zero-carbon, reduce commercial emissions 72 percent and residential emissions 55 percent; if fuel oil and propane customers switch to gas, reductions of 72-76 percent required

Average number of buildings that must be decarbonized to meet state targets: 3,459 business and 27,926 homes per year (with no gas switching), 4,260 commercial and 59,758 homes per year to 2050 (with gas switching)

Natural gas expansion (in 2017): 21,860 residences, 1,729 commercial buildings

Rhode Island

Overview: Burning fossil fuels in buildings accounts for 27 percent of Rhode Island’s total energy-related emissions. The state has also established the following goals for carbon emissions reductions: 10 percent below 1990 levels by 2020; 45 percent below 1990 levels by 2035; and 80 percent below 1990 levels by 2050.

Building emissions target (reductions): if all fuel oil and propane customers switch to zero carbon, 66 percent reductions from commercial gas buildings and 53 percent reductions from residential gas buildings by 2050

Average number of buildings that must be decarbonized to meet state targets: 540 commercial buildings, 4,334 homes each year to 2050 (779 business and 9,212 homes per year with gas switching)

Natural gas expansion (in 2017): 2,440 residences, 82 commercial buildings

Earlier this year, Gov. Gina Raimondo signed an executive order aiming to transform the state’s heating sector, with a final report expected next spring.

Maine

Overview: Burning fossil fuels in buildings accounts for 27 percent of Maine’s total energy-related emissions, the majority of which comes from oil. The state has also established targets to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 45 percent by 2030 and 80 percent by 2050. Building emissions target (reductions): switch all oil and propane customers to zero-carbon by 2050, plus 7 percent reduction of existing gas commercial customers; gas switching by fuel oil and propane customers requires 66-75 percent sector-wide reductions by 2050.

Average number of buildings that must be decarbonized to meet state targets: with gas switching, 800 commercial and 12,000 residential buildings each year to 2050

Natural gas expansion (in 2017): 1,097 residential buildings, 232 commercial buildings

New bills signed into law by Gov. Janet Mills in June 2019 included the goal of installing 100,000 energy efficient heat pumps in homes and businesses across the state to leapfrog the risks of gas switching. Despite these ambitions, Maine still added more than 1,300 new buildings to the gas system in 2017.

New Jersey

Overview: Burning fossil fuels in buildings accounts for 20 percent of New Jersey’s total energy-related emissions, the majority of which comes from gas. The state reached its 2020 emissions reduction goal ahead of schedule and has now set its sights on achieving an 80 percent reduction in carbon emissions (from the 2006 baseline) by 2050.

Building emissions target (reductions): switch all fuel oil and propane customers to zero-carbon, reduce emissions from existing gas buildings 75 percent

Average number of buildings that must be decarbonized to meet state targets: 6,195 existing gas commercial buildings, 72,287 existing gas residences every year to 2050

Natural gas expansion (in 2017): 32,037 homes, 1,206 commercial buildings

New Jersey’s recent energy master plan makes clear the importance of electrifying buildings to achieve climate targets.

A Choice between Two Paths

As we’ve seen in the data above, converting existing fuel oil and propane customers to natural gas is insufficient to achieving state-mandated climate goals. Even buildings currently heated by gas – irrespective of new customers being added to the gas system or moratoria on gas in new construction – must be rapidly decarbonized over the coming decades.

Although this challenge is most severe today in the states listed above, we expect other states to require similar levels of efforts– especially as the building sector begins to contribute a proportionally larger share of total greenhouse gas emissions as progress continues in transportation, electric power, and industry.

Two broad schools of thought have emerged to address this issue. One school says that we should continue to utilize and expand the existing gas system for decades to come, one day replacing fossil gas with lower carbon alternatives through biological or chemical processes (e.g., biogas, “renewable natural gas”, synthetic methane, or electrolysis hydrogen).

The alternative is to electrify buildings, which today will reduce emissions compared to gas, and savings will increase over time as the power sector continues to clean up. Based on RMI analysis, we know today in most states electrification not only reduces emissions and in many cases saves money, but also can allow buildings to participate in electricity markets as demand-side resources. This further lays the groundwork for new renewables and further decarbonization of the power sector and, in turn, the building sector. This virtuous cycle deserves further consideration.

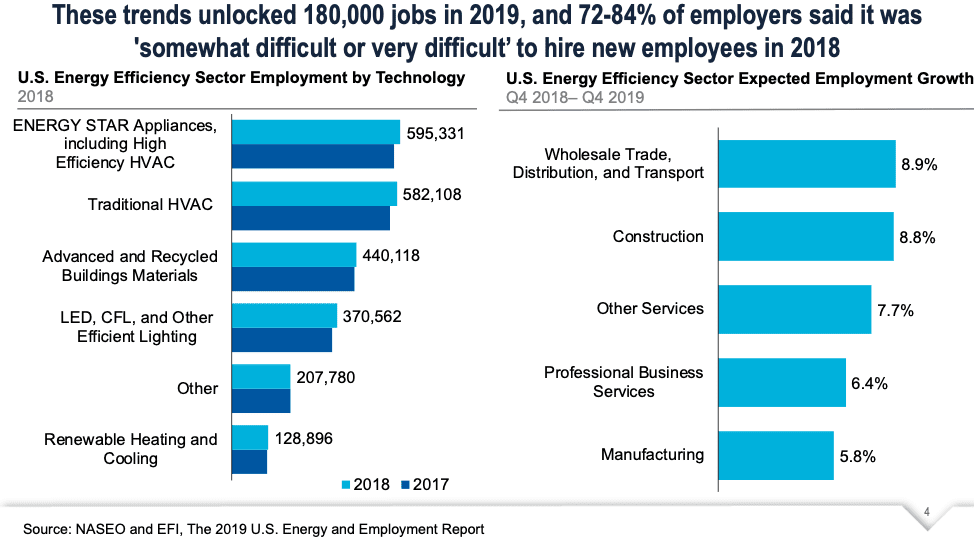

These targets are daunting, but they also present one of the largest opportunities for job creation in our economy today. Research published this year suggests that the trend toward electrification and building efficiency created 180,000 jobs in 2019, with 5.8–9.9 percent annual growth in 2019, far outpacing other sectors. We expect these trends to continue as states begin to require all-electric new construction, and as more customers learn about and adopt lower-carbon, lower-cost electric alternatives for heating, cooling, and cooking.

A strong case for electrification is shown by our work to date on this issue, as well as our observations of the demonstrated data, political engagement, advocate support, and organic customer momentum toward electrification. This can be contrasted with the excessive cost and lack of availability of zero-carbon gas.

Even by the American Gas Foundation’s own analysis, the technical potential of “renewable natural gas” is inadequate to supply all of today’s buildings and industry, let alone electric power. This underscores the importance of ensuring scarce zero-carbon gas resources are utilized for the hardest-to-abate end-uses like industrial processes, manufacturing, and heavy transportation.

We’re ready to get started on the hard work of electrifying buildings today. Individuals, cities, and states have the right to choose the right zero-carbon pathway for their buildings, and we can’t wait around for zero-carbon gas to show up.

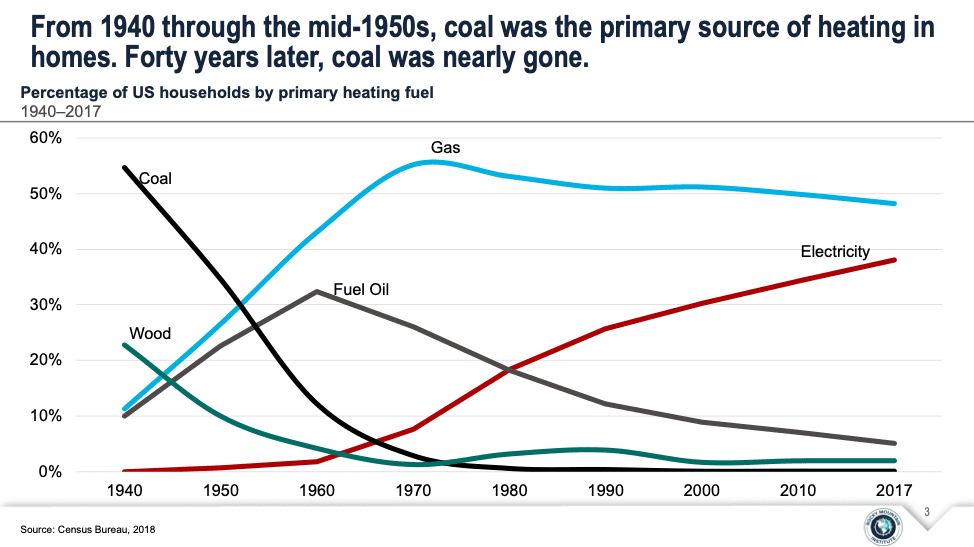

America has done this before: in forty years, coal went from the majority heating fuel in American homes to nearly gone in 1980. But this time, we have only thirty years.

Analytical disclaimer: We have assumed that the building sector must contribute emissions reductions proportional to their share of state economy-wide reductions. All data is from EIA with internal RMI analysis unless otherwise stated. The annual number of customers to be decarbonized is an average; in reality, we expect (consistent with past fuel switching trends) that the number of customers who fuel switch will start small and ramp up to an even higher annual number than stated in these narratives. It is important to electrify all existing oil and propane customers as soon as possible, but that’s not enough. Banning new gas connections is not enough. States serious about their climate goals need to start decarbonizing existing gas buildings as soon as possible.