Five Takeaways from the Latest Global Energy Analysis

As world leaders gather in Brazil to spur climate action, the latest global energy analysis from the IEA shows its widest-ever range of scenarios — although only one reaches the broadest benefits.

With world leaders gathered on the edge of the Brazilian Amazon to spur action on climate change, the International Energy Agency (IEA) has released its annual World Energy Outlook, the “most authoritative source of global energy analysis.” The outlook explores how the global energy system could evolve through scenarios with different assumptions about government policies, technology costs, and climate targets. The range of scenarios has never been wider — reflecting ongoing shifts in the global energy transition — but only the net-zero scenario achieves the broadest benefits.

Given the breadth of possibilities, many are asking which scenario represents the most likely future. Some think it is the new Current Policies Scenario (CPS), despite its lack of policy improvement “even when governments have indicated their intention to do so.” Others continue to focus on the Stated Policies Scenario (STEPS), a “dynamic reading of today’s policy settings.”

However, IEA is clear that no scenario is a forecast; none should be assumed to foretell the future. Instead, it is crucial to compare these scenarios to recent trends on the ground, where progress has outpaced expectations — with vast potential to accelerate. Here are five charts and takeaways along those lines.

1. Cleantech has often outperformed “current policy” outlooks

To evaluate these scenarios, it is helpful to assess how past versions have performed against recent reality. In the case of solar power, wind power, and EVs, deployment has been up to two to three times faster than the previous CPS had projected in 2019. That year’s STEPS wasn’t much closer.

Other metrics are mixed; coal demand and its emissions were still rising until a recent plateau. But it’s clear that for fast-improving clean energy technologies, progress has greatly outpaced scenarios tied to “current” or “stated” policies.

This makes sense given how the scenarios are designed. According to the IEA, the CPS expects constraints that lead it to “project slower adoption of new technologies than has been seen in recent years.” This year’s CPS is similar, assuming a lack of policy implementation such as the planned emissions trading schemes in India, Turkey, and Brazil. Treating this as a “business-as-usual” forecast would ignore the history of clean energy progress.

2. The world continues to be off track for net zero

On the other hand, progress has not nearly been fast enough for IEA’s Net Zero Energy (NZE) scenario, a world that reduces CO2 emissions to net zero by 2050. In recent years, emissions have continued or increased across CO2, methane, and other key climate pollutants — a far cry from the latest NZE scenario, which requires a 2x decline for CO2 and a 5x drop in energy-related methane by 2035.

The reasons are many, but a major one is the lack of progress on energy efficiency. Feasible efficiency improvements across the system could save trillions while accelerating the pace of the energy transition by a decade or more. As a result, more than 130 countries pledged in 2023 to double the rate of annual efficiency improvements, from the 2 percent baseline in 2022 to 4 percent every year as in the NZE scenario. But rather than doubling, annual improvements have fallen below that baseline, putting those savings further out of reach.

At the same time, baseline electricity access remains a consistent issue. While the original NZE scenario in 2021 trended toward universal electricity access by 2030, the number of people without electricity has remained above 700 million ever since. Falling behind that scenario imperils far more than emissions progress; it hinders prosperity for communities around the world.

3. Still, some technologies are accelerating ahead of net-zero trajectories

However, not all metrics are behind pace. Compared to previous Net Zero Energy scenarios, solar and battery deployment are actually running ahead of schedule, although other assessments may differ in methodology.

Both metrics have roughly reached the original net-zero scenario’s 2030 deployment rate already, in 2025 — and although this rate stagnates under the newest “current” or “stated” policy scenarios, history shows a different story. If manufacturing can continue to outpace expectations, while confronting crucial challenges from concentrated supply chains, these positive trends could continue.

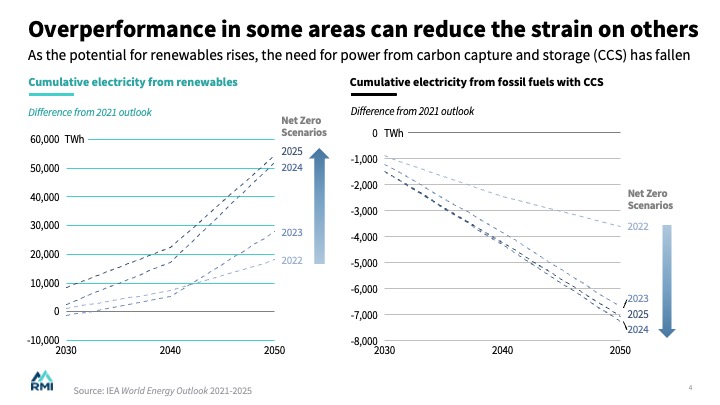

4. Overperformance in some areas can reduce the strain on others

In theory, these success stories can reduce the scale-up requirements for more nascent solutions, as in the case of carbon capture and storage (CCS). As the potential for renewable electricity deployment rises in each net-zero scenario, the need for CCS in the power sector has usually fallen slightly. Achieving this shift requires many enabling conditions, from grid deployment to the full portfolios required for reliability, but the trend is moving in a positive direction.

IEA and RMI both recognize that carbon removal will be required in the long term to alleviate the carbon already in the atmosphere, but neither it nor point source carbon capture is needed where clean energy alternatives exist. If less CCS is required for electricity, it can focus on areas that are harder to solve, scaling at a more reasonable rate.

5. We can benefit people’s lives by securing a clean energy future

Above all, it’s important to remember why these trends matter for people around the world. As UN leader Simon Stiell has said, humanity can only win this fight “if we connect stronger climate action to people’s top priorities in their daily lives.”

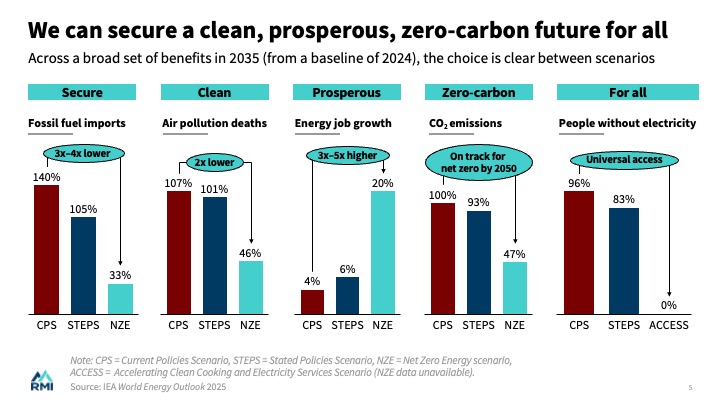

At RMI, the key is transforming the global energy system to secure a clean, prosperous, future for all. Each of those words matters, and each has a corollary in IEA’s data that shows a drastic difference between the new scenarios in 2035 alone.

For the three in four people who live in fossil fuel importing countries, a path with more domestic renewables means that fossil fuel import costs could be two-thirds less than today’s. A clean future would mean less than half as many deaths from air pollution, along with three to five times the job growth for a more prosperous energy sector. Climate pollution could be halved, on the way to net zero by 2050, and electricity access could still be achieved for all.

With these far-reaching data points, the choice is clear. If we treat IEA’s scenarios not as forecasts but as futures to compare, we can learn from their findings and chart a path to reach the broadest benefits.