Does Wasting Home Heating Make You See (Infra)red?

Have you ever wanted x-ray vision, or to see the hidden features of your home? The City of Vancouver has launched a new effort to make energy use more visible to its residents, complete with rainbow-colored images of their homes that show details invisible to the naked eye. Using thermal imaging to show heat loss in roughly 15,000 homes in five neighborhoods, Vancouver aims to help residents uncover wasted energy. How can making invisible aspects of a home visible drive energy savings and economic development?

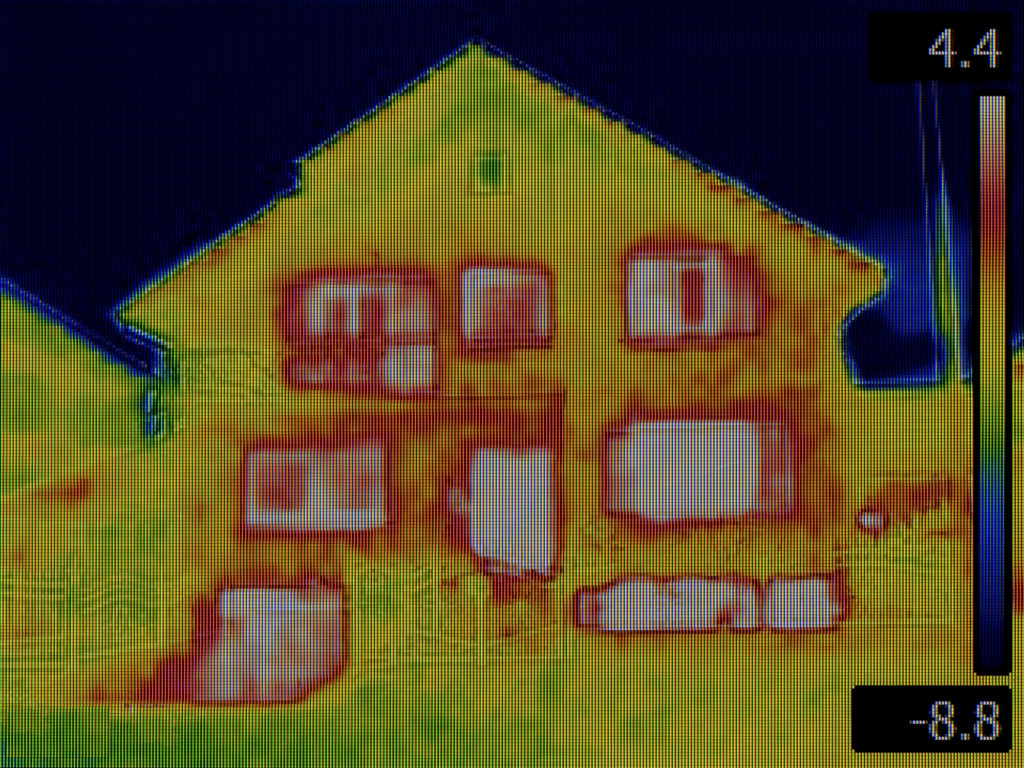

The allure of invisibility has been with us for a long time. Stories ancient and modern have explored the idea, including Harry Potter’s cloak, James Bond’s invisible car, and of course Frodo’s ring. But some things are already invisible in ways that create real problems. Look at the homes in the picture below. Which one is energy efficient? Homeowners want energy efficient homes, but they can’t easily tell the difference. The invisibility of energy use creates transparency problems in the market, which are starting to be addressed in a variety of ways.

Infrared Thermography

Vancouver’s program is based on infrared thermography (IRT) of each of the 15,000 homes. IRT is a way of taking pictures that captures the heat emitted from objects. This creates an image of temperatures, warm and cold, instead of the colors and shadows that we see with our naked eyes or in standard photography. This is great way to find areas of heat loss in a home, essentially providing a guide to the parts of a home that cause discomfort and require the furnace, boiler or air conditioning to work harder and consume more energy to meet temperature demands. Thermography can also reveal materials with water damage, since those hold heat differently than dry materials.

Thermographic images are also recognizable for being colorful and distinct. By revealing invisible heat losses and allowing a new way of seeing one’s home, these images have the allure of a new technology. And although thermographic images have been around for some time, IRT cameras are becoming more common and inexpensive. Portable versions made to be a smart phone accessory retail for $250, compared with the $14,000 price that professionals had to pay only 10 years ago. Now a collection of 10 neighbors could purchase one to share for only $25 each. But to get the most out of it, they would need to learn how to use it well. Professional thermographers know sophisticated techniques and understand the limitations of the technology. One limitation of IRT for home assessment is that it requires at least a 30-degree difference between indoor and outdoor temperatures to work best. Without such a difference, the heat loss through the structure may not be apparent. This is why Vancouver’s pilot is being run over the winter.

Programs like Vancouver’s are further limited by only capturing images of the homes’ front and side, which won’t reveal heat loss from other places in the homes. This approach is a result of using car-mounted cameras to scan entire neighborhoods, but it may produce false negatives. For example, a scanned home may appear to have no heat loss if heat was primarily leaking from the back of the building.

The primary purpose of the pilot is to test a variety of approaches, including comparing letters to homeowners with IRT images and without, to see if they motivate more residents to take action. According to Chris Higgins, Green Building Planner with the City of Vancouver, they are testing a variety of approaches in the pilot and will have public results available in spring of 2018.

The Economics

Vancouver’s pilot program will cost approximately $6 per home. The question is, how much will it drive energy-upgrade action among those homeowners? Essess, the company delivering the program for Vancouver, has performance results from similar programs in the past. According to a 2015 Navigant study, a similar program resulted in 3.8 percent of households responding to a mailer containing a thermographic image of their home. This response rate was 2–4 times greater than the usual response rates of other utility programs.

If we assume 2 percent of homeowners, or roughly half of those who respond, take action and are so converted into project leads, then the Vancouver program works out to have a cost of roughly $300 per project lead. A cost of $300 per lead is common for the home improvement industry, or maybe even a little low. If those homeowners take actions that work out to an average of $1,000 in activity on each home, either by hiring contractors or by spending equivalent sums to do it themselves, then this campaign would generate roughly $300,000 in economic activity—a three-to-one multiplier for the program costs. Higgins says that if the pilot results in a $300 cost to get residents to take action, they’d consider that a success.

What this means for the industry

Research has shown that a direct mail campaign using a house list (an internal mailing list for existing customers) has an average response rate of 3.7 percent. Given that the city has an existing relationship with its residents, the 3.7 percent response rate for “existing customers” should be a fair comparison baseline for IRT-enhanced direct mail. The average response rate research comes from a 2015 report from the Data & Marketing Association, chosen since the Navigant study referenced above was also from 2015. Since regular direct mail for house lists had a nearly identical response rate to the IRT-enhanced outreach in 2015, it will be useful for the industry to see Vancouver’s pilot results with a direct control group.

If the response rates remain the same, this may imply that the primary benefit of thermography programs is in the personalized approach they deliver for each home, more than the thermography itself. Whether the specific analysis or the colorful pictures drive more residents to take action remains to be seen. Essess has been working on improving how it delivers its services, and the Navigant study is several years old. Moreover, having cities lead efforts like Vancouver’s may produce very different results than having utilities lead such efforts, given that residents’ trust relationships can be very different with city governments and utilities.

Measuring the success of the Vancouver program should provide important insights to what this approach can deliver.

The other question is not just whether thermography programs can reach more homes, but whether they can reach different homes. Does the highly visual image, with its new-technology glamour, reach a different audience than traditional efficiency marketing? If so, then the number of homes reached could remain comparable to other programs but still represent a major breakthrough.

The neighborhood sweep approach for this program brings an additional component to efficiency marketing: social norms and peer pressure. By focusing on an entire neighborhood at a time and publicly sharing that approach (though not publicly sharing information about individual homes), the program has a greater chance of building on word of mouth and social norms for the neighborhood. Neighborhood thermography could support growth of efficiency efforts similar to that produced by the solar contagion effect. Also, as real estate listings continue to capture more information about homes and home energy, thermal imaging could provide a new aspect of information about neighborhoods and individual homes.

To improve the social norm impact of thermal imaging programs, we would recommend adding an image of a high performing home as a point of comparison. This would help define what’s possible and highlight the deficiencies in the current home. Ideally, this high performing home image could be drawn from the same neighborhood. This would require getting the high-performing home owner’s permission of course, but would create an opportunity to highlight champions in the neighborhood and engage the early adopters who may not have much interest in the program otherwise.

Home energy efficiency will never have a silver bullet that engages all residents. Rather, moving the market requires what energy mavens have long called “silver buckshot,” a variety of approaches that solve a variety of problems. Thermography-based programs may help reach more households, or different households, by providing a personalized, visually striking analysis of people’s homes.

Images courtesy of iStock.