City Communication Technology of Manhattan

Decarbonizing NY Buildings through Improved Data and Controls

Building decarbonization is a critical thread to reduce the impacts of climate change—buildings are the single-largest contributor of emissions globally and their operations alone account for 28 percent of global energy-related annual CO2 emissions as of 2018. To affect operations and contribute to the decarbonization of the built environment, building owners and operators need to see, understand, and control what is happening in their buildings—including in tenant spaces.

According to a 2017 report by the Urban Green Council, space heating, plug loads, and domestic hot water consume the most energy in New York City’s large buildings. Those are all loads that, with the right controls, could be shifted to reduce cost and resulting carbon emissions. In office buildings, 22 percent of energy is used by either unknown or highly specialized loads, termed “other” in the distinctions outlined by city law. This is closely followed by plug load (18 percent) and lighting (13 percent).

Exhibit 1: NYC’s Large Buildings Energy Use Ratios

How do buildings see, understand and control the various sources of energy spending and carbon emissions in their building, especially if there are multiple fuel sources, for multiple end uses, across multiple tenants’ spaces? A growing number of large commercial buildings have some level of base-building equipment-metering systems which can expose thousands of raw data points, but those systems may lack the analytics or dynamic controls to synthesize trends or respond to an optimization function. Building monitoring systems are notorious for inundating building operators with dashboards and visuals without providing actionable insights to improve operations and reduce operating expenses.

What is an Energy Management Information System?

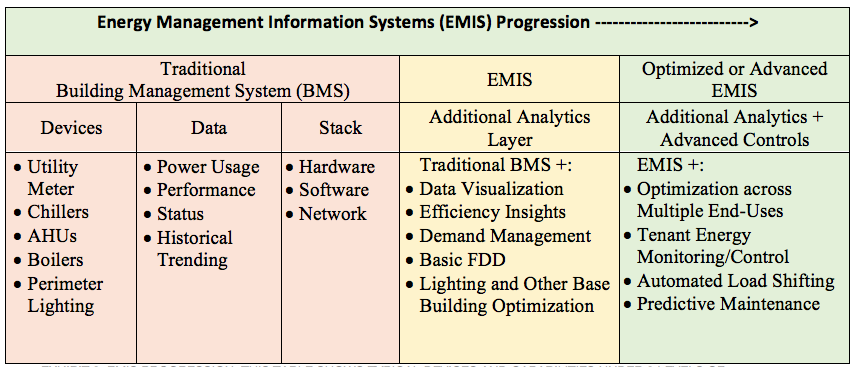

Energy management systems (EMS) or energy management information systems (EMIS) are a proven solution that can be added to an existing building management system (BMS) to deliver more real-time monitoring, analytics, and alarming geared toward energy and cost savings. EMIS and resulting efficiency adjustments have shown a reliable 8 percent median energy consumption reduction according to analysis by Berkeley Lab and New York’s successful Real Time Energy Management (RTEM) program administered by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority.

These types of capabilities require investments in upgrades or overlays to a BMS which typically provide basic metering and alarming but not the type of data analytics and reach required to see and understand energy use beyond base building HVAC loads. An additional layer of high-speed networking and software on top of isolated BMS-controlled end-uses, like HVAC and tenant loads, allow for an umbrella-like architecture to stage energy uses as if they were a singular system.

A 2016 report notes that, in NYC, around 35 percent of large multifamily and 25 percent of commercial buildings have deployed some sort of energy management system. Energy monitoring capabilities fall along a wide range, with many options in between.

Exhibit 2: EMIS Progression: This table shows typical devices and capabilities under 3 levels of sophistication

A key challenge even for the most advanced EMIS deployments is penetration of tenant spaces (typically the challenge is more the legalese of lease structure and split incentive versus technological barriers). The large end use loads of space lighting, plug loads, supplemental HVAC, and the mysterious “other” are not being affected by the monitoring and analytics being performed on the base-building systems. In some cases, tenant spaces are submetered (and in NYC, all non-residential tenant spaces over a certain size must be submetered by 2025 or face fines under Local Law 88) but the implementation to date has been haphazard and inconsistent.

Measuring these end uses alone would contribute to savings if we are to learn from other examples of master meter versus submeter behavior differences. For example, according to New York City’s report, the benchmarking and audit data indicated that direct-metered multifamily buildings consumed less electricity per square foot than master-metered buildings. Further, the data indicates that buildings with distributed air conditioning systems used less energy, even though central system equipment is almost always more efficient per unit of cooling produced. Behavior and operations play an outsized role in efficiency, and there is no way better way to implement some level of accountability than collecting and visualizing performance data.

Beyond the carbon reduction needed from the building stock, vacancies brought on by the coronavirus pandemic have highlighted the need for much more effective control and load management strategies. Despite reduced occupancy in commercial buildings during the coronavirus pandemic, commercial building owners and operators have gotten a rude awakening by the fact that they have little ability to drive energy reductions beyond 25 percent. In the Empire State Building for example, energy use dropped by just 28 percent even though it was nearly 100 percent unoccupied.

Unsure of specific re-occupancy timelines and lease agreements as a barrier to fully turning down the building’s energy use, most buildings continue to operate heating, ventilation, air conditioning, and lighting even with occupancy levels near zero. Building owners need to leverage energy management information software and services to understand and cut their energy usage—and not just at the base building level. Much of the persistent loads in unoccupied buildings are coming from tenant spaces, and remain unidentified to building operators who do not have a way to parse out tenant space energy use and costs beyond spotty submetering.

Having a robust monitoring and analytics platform installed (i.e., an Advanced EMIS) offers a launching platform for other valuable opportunities—which have only increased over time with the emergence of more robust demand flexibility markets and stringent carbon abatement laws.

Over the past five years, energy management information software and services have vaulted from mostly energy spend (kWh) focused to demand (kW) focused, enabling buildings to not only monitor their energy output, but also strategically shed and shift load. Building energy management information systems now give buildings the ability to optimize their energy consumption across multiple end uses (e.g., heating, cooling, lighting, plug loads, etc.), and integrate various signals (e.g., cost, occupant count, carbon intensity of the grid). For instance, an energy management and information system can control when an electric water heater runs so it doesn’t coincide with the operation of a cooling compressor. This reduces a building’s peak demand, which can make up to 60 percent of the owner’s total electricity costs.

If a critical mass of buildings reduced or shifted their peak demand away from key times, it would also reduce the need for peaker plants, which are often dirtier than other generation resources. Co-optimizing battery charge and discharge times based not only on cost signals but also on carbon signals, can sustain cost savings while reducing carbon emissions by 32 percent according to a recent study by enel x and WattTime.

EMIS in Action

As the single-largest source of emissions (~73 percent) in the city, buildings are vital to the climate goals of NYC and New York State under the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (CLCPA). Among a number of energy focused bills under the Climate Mobilization Act, Local Law 97 is a buildings performance-based and carbon-focused mandate that penalizes the city’s largest 50,000 buildings if they do not reduce their greenhouse gas emissions by 80 percent below 2005 levels by 2050 (“80×50”).

It is anticipated that over 75 percent of buildings in New York City will need to invest in building improvements by 2030 to avoid fines under Local Law 97. Beyond energy savings and operational improvements, an advanced EMIS system can help building owners understand in real-time how their buildings are performing against LL97 caps and it can act as an M&V platform to ensure other retrofit investments are performing as promised and necessary for compliance with the caps.

Most building owners have already identified and acted upon the obvious low-hanging fruit—they do not need to be reminded how many kWh they save with an LED retrofit or by installing solar on their roof. However, there are a range of low-cost but not as obvious (in that they are more building system, envelope, and occupant dependent) measures that are based on the type of data an owner/operator gets from an EMIS. For example, for a commercial building that typically ramps up HVAC early in the morning, a data-based implementation of optimal start-stop can result in electricity savings in excess of 19 percent over baseline.

To identify and have confidence in the mid- to high-cost decarbonization measures and operational optimizations, building owners and operators need the granular visibility and controllability that is not commonplace in most buildings today. Programs like NYSERDA’s Real Time Energy Management (RTEM) have flagged the necessity of being able to visualize and understand granular energy spend across the majority of building end uses in order to be able to have a significant impact on its footprint. This program offers cost share to implement advanced EMIS and hopes to see more NYC buildings jump on the opportunity to invest in a tool that will continue to have strong returns as New York state completes its energy transition and decarbonization goals.