Build Mixed-Income Housing in Wealthy Urban Neighborhoods

Changing our zoning laws to allow mixed-income housing in higher-income, urban or walkable neighborhoods can improve climate and equity.

The United States is emerging from the acute health and economic crises wrought by the COVID-19 pandemic to a longstanding housing shortage that is only worsening. The compounding harms of this nationwide crisis range from cost burden and inadequate housing to displacement and homelessness. Estimates of the gross shortfall range from 3.8 million to as many as 6.8 million homes with an especially severe deficit of rental housing accessible to very low-income households.

California’s housing shortage has been so severe that a decade-long economic boom was accompanied by the exodus of nearly a million low-income Californians, often to higher emitting states. This culminated in an unprecedented net population loss for the state in 2020 as well as the loss of a Congressional seat.

The shortage is so deep that even many middle-income households are not able to find sufficiently affordable housing near their jobs, causing them to drive more. In 2017 transportation surpassed electricity to become the largest source of climate pollution in the United States. A majority of this pollution comes from people driving passenger cars and trucks. Most troublingly, increases in private car travel have historically outpaced vehicle efficiency improvements to drive increasing carbon emissions. In fact, efficiency improvements alone tend to induce more driving, along with highway expansion that has far outpaced population growth.

Therefore, we must not only move from conventional efficiency toward rapid vehicle electrification, we must also reduce vehicle miles traveled by investing in inclusive, complete, compact, transit-oriented communities. And to do this equitably, we must change our zoning laws to allow mixed-income housing in higher-income, urban or walkable neighborhoods.

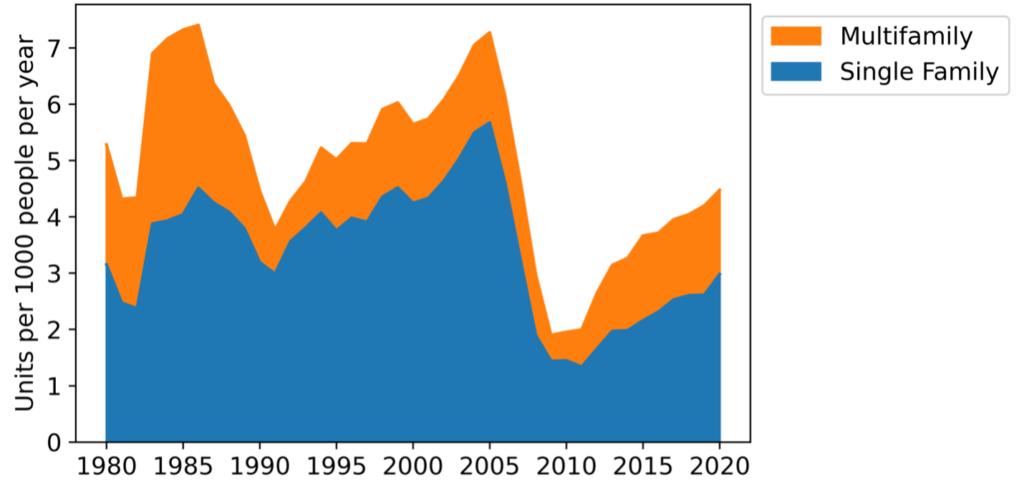

Exhibit 1: US Homes permitted annually per 1,000 residents from 1980–2020.

Source: RMI analysis based on https://housingdata.app/

Zoning: A Common Underlying Cause

The primary obstacle to building more homes and reducing car dependence is one and the same: exclusionary zoning. Largely developed as a means to segregate by race and class, planning rules which mandate building detached single-family homes on large lots have continued to proliferate after the end of legal segregation, even extending into urban neighborhoods that previously built apartments. In fact, the majority of San Francisco’s existing housing stock would be illegal to rebuild today. Discretionary review processes that disproportionately empower wealthy, white homeowners to block new multifamily housing exacerbate the effects of exclusionary zoning.

By spreading out homes from each other and separating them from destinations, these planning rules encourage car-dependence, particularly when coupled with mandatory minimum parking requirements. In this way, most places in the United States have effectively made it illegal to build new housing in walkable neighborhoods.

Even though surveys show about half of US residents would prefer to live in walkable neighborhoods even if it meant smaller homes, these planning rules limit access to these neighborhoods by limiting the supply of homes. Prices are bid up on the limited supply, leaving only wealthier households able to access compact communities close to jobs and services—the same communities which inherently generate less climate pollution per household.

A Historic Opportunity: Promoting Infill Development in Low-Carbon-Footprint Neighborhoods

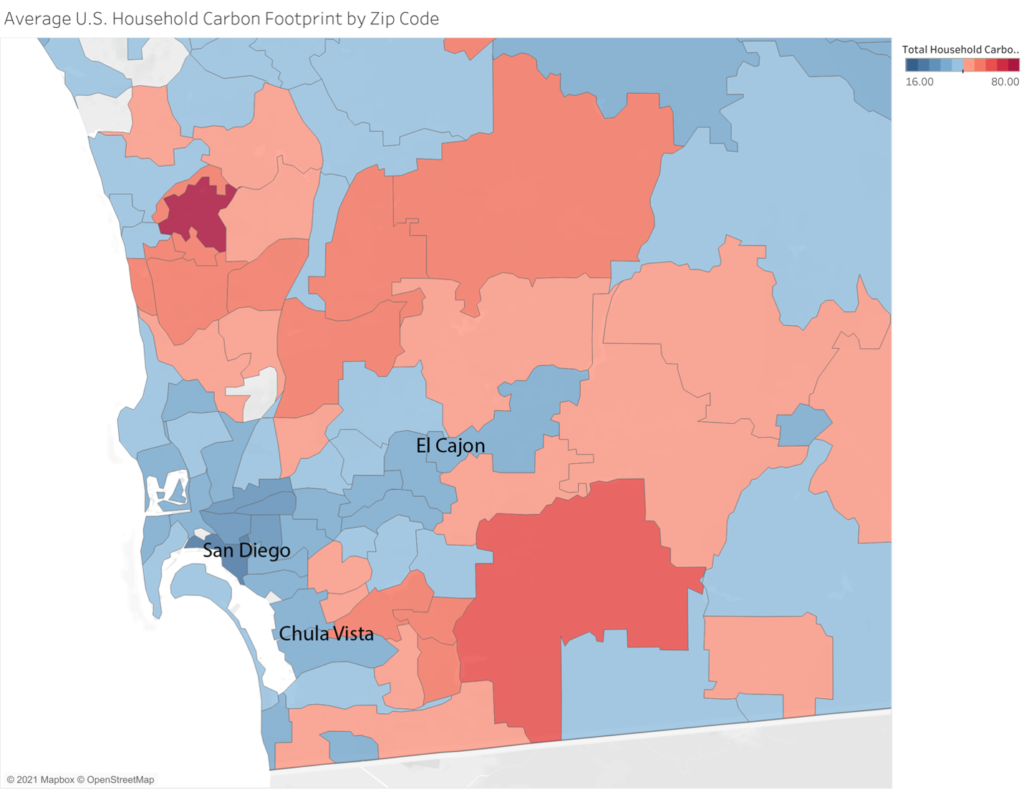

Researchers at the CoolClimate Network developed consumption-based carbon footprints for every zip code in the United States. The calculated consumption-based footprints allocate all emissions back onto households, including those generated elsewhere to provide them energy, goods, and services. Browsing their online map, one can readily see the same pattern all over the United States: low-emitting urban cores surrounded by high-emitting suburbs.

Indeed, after controlling for income, they found that population density was a strong predictor of household carbon footprint. What this means is that a family at a particular income level will tend to contribute substantially less to global climate change when living in denser urban neighborhoods. The biggest single mediating factor was found to be fewer cars owned per household, though all emissions categories contributed. In fact, recent studies have confirmed the significant role of building energy consumption, showing that federal policies favoring single-family homes has increased residential energy and emissions.

Exhibit 2: Year 2014 household greenhouse gas footprint (tons CO2e/yr) by US zip code in the San Diego region

Source: UC Berkeley CoolClimate map.

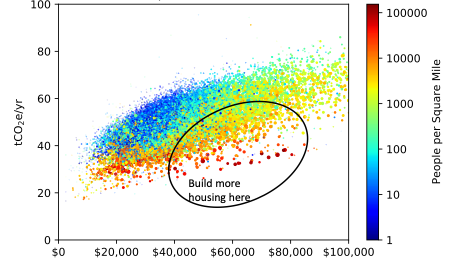

Exhibit 3: Year 2014 household greenhouse gas footprint vs. household income, by US zip code. Dot size is proportional to zip code population.

Source: RMI analysis based on UC Berkeley CoolClimate data.

Partly due to deficient analytical approaches, US climate policy advocates have largely ignored the greenhouse gas reduction potential of land use reform. While it’s true that we cannot replace our housing stock overnight, the potent impact of land use on household carbon footprint combined with the historic housing shortage provide a critical opportunity to address our climate, air pollution, and equity goals.

For the United States to catch up with population growth and fill the housing shortage, we may need to build upward of 20 million homes in the next decade. From the CoolClimate maps and Exhibit 3, one can readily observe a 10 to 20 ton CO2-equivalent (tCO2e) per year difference between the higher- and lower-emitting zip codes at the same income level, loosely corresponding to building new housing in the suburban fringe versus new urban infill.

Combining these two factors suggests that building the needed new housing in the right places could avoid roughly 200 million tCO2e per year by 2030. This is equivalent to the emissions savings provided by an ambitious building electrification policy reaching 100 percent appliance sales in 2030.

Avoiding further destruction of the natural and working land carbon sink from development would add to this estimate; historic urban and suburban development has already degraded the land sink by 80 million tCO2e per year. This could also avoid further building in the wildland-urban interface, areas of higher water stress, and other locations vulnerable to climate risk.

CoolClimate researchers assessed the potential for urban infill to reduce emissions in 700 California cities and developed an online scenario tool. Their tool shows a statewide potential of up to 15 million tCO2e from urban infill housing. Moreover, it projects urban infill to be the largest opportunity for reducing climate pollution through local policy for many California cities, including San Francisco, San Diego, Sacramento, and Oakland. RMI is planning to work with CoolClimate to extend this calculation to other states, and will be publishing more in-depth research on this topic over the next few months.

Reform Planning Rules to Unlock a Historic Opportunity

Building mixed-income housing in higher-income, urban, or walkable neighborhoods is a solution for both climate and equity. Targeting “upzoning” policies (policies that increase density) toward higher-income neighborhoods expands access to opportunity and counters rather than risks contributing to further gentrification and displacement in low income urban neighborhoods.

Density bonuses and facilitating “affordable by design” missing middle housing offer cost-effective approaches for promoting integrated communities when upzoning. Inclusionary zoning policies, which set affordable housing minimums on new development, also further this goal as long as the requirement is not prohibitively stringent.

Around the country, examples abound of wealthy, walkable or transit-rich, lower-carbon-footprint communities that largely restrict new housing. These include university-oriented cities like Missoula, MT, and Cambridge, MA; and neighborhoods in or bordering major cities from Clarksville in Austin to SoHo in New York City. Many of these places voted overwhelmingly for President Biden, whose administration has repeatedly called for reforming zoning and building more homes. It remains to be seen if they will follow this direction in their own communities.

For too long, much of the US environmental movement has been more focused on stopping environmentally destructive practices rather than supporting environmentally beneficial development and infrastructure—and has sometimes missed the mark when choosing what to oppose. While this can even extend to building renewable energy infrastructure, perhaps the most damaging impact has been environmentalists’ culpability in creating the housing crisis.

The rise of a new pro-housing coalition in US cities strengthens the hand of the “smart growth” movement within environmentalism. Combined with a resurgent racial justice movement and a vigorous youth climate action movement—people of color and young people are disproportionately impacted by both the housing and climate crisis—there is a historic opportunity for climate advocates to help catalyze social transformation. If climate advocates join the pro-housing movements in their own communities across the country, we can usher in a zero-carbon future filled with abundant, climate-friendly housing, for all.