The Wonders of Weatherization: Improving Equity through Stimulus Funding

COVID-related health impacts and financial hardship have disproportionately affected people of color in the United States. At the same time, the protests over the killing of George Floyd have further emphasized the need to address this country’s systemic racial inequities. Rather than allowing racial inequality to worsen further, Congress can provide money to federal programs in ways that address some of these racial disparities in addition to boosting the economy.

One such program that fits the bill here already exists—the Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP), which funds and implements home energy retrofits that help low-income families reduce their energy costs. Ongoing coronavirus stimulus efforts can inject additional funding into this program while applying lessons learned from a past stimulus effort, the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), to improve energy affordability, create jobs, benefit public health, and advance racial and income equity.

COVID-19 Further Amplifies Inequities in Energy Affordability

A recent analysis found that the number of American business owners fell 22 percent from February to April 2020, and this number is split unevenly by race. While the number of White business owners dropped by 17 percent, the number of Latinx and Black business owners fell a staggering 32 percent and 41 percent, respectively. This is happening as part of a broader, longer-term issue: people of color are experiencing disproportionately high unemployment and economic stress, both before and after the pandemic began.

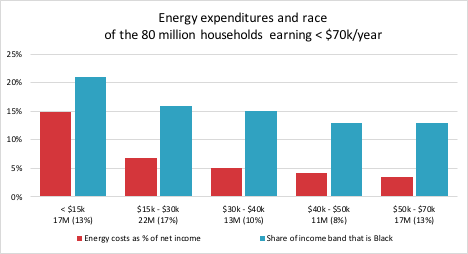

According to the Department of Energy (DOE), every home it weatherizes saves its occupants an average of almost $300 annually on energy bills and provides total benefits, including health and safety, of over $13,000. It can also reduce non-financial stressors by improving comfort, and in some cases reducing noise or pests. Low-income residents have higher energy burdens, meaning that they pay a higher percentage of their income on energy costs, than higher-income residents. And the very lowest income bands, which have higher energy burdens, are disproportionately Black. Thus, weatherization through programs like WAP improves racial and income equity.

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Expenditure Survey 2018

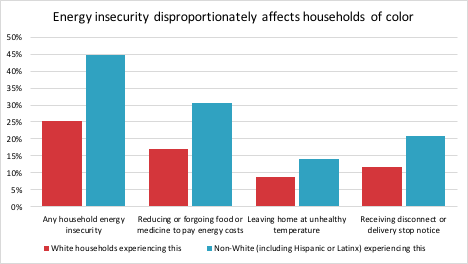

Low-income households also live in less efficient housing and pay more for energy on a per square foot basis than non-low-income households. They also experience energy insecurity more often, meaning that they face challenges paying energy bills or adequately heating or cooling their homes. Non-White households also disproportionately experience all types of energy insecurity; 45 percent of non-White households—a staggering 15 million households—experience some type of energy insecurity.

Source: US Energy Information Agency, Residential Energy Consumption Survey 2015

WAP Is a Good Stimulus Investment

By weatherizing homes at scale, stimulus investment in WAP has the potential to mitigate inequitable energy affordability challenges. Since it began in 1976, WAP has weatherized more than 7.4 million single-family homes, mobile homes, and multifamily units. Despite this progress, there is still a huge unmet need—the program reaches less than 1 percent of the 30 million eligible households per year because it has been chronically underfunded.

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009 invested $2 billion in WAP, which funded the weatherization of over 340,000 low-income homes. This yielded program-wide energy savings of $1.1 billion and total benefits of $4.5 billion, supported 28,000 jobs, and reduced nearly 7.4 million metric tons of carbon, equivalent to removing 1.6 million cars from the road for a year. However, ARRA funding still did not come close to matching the total scale of the need for low-income weatherization.

WAP is a good investment because it directly addresses the problem of energy affordability and equity. While Black Americans represent only about 13 percent of the country’s population, 28 percent of the WAP retrofitting projects funded through ARRA in 2010 benefitted Black households. Viewed this way, WAP can be an example of “targeted universalism:” if a goal is to eliminate energy burdens from all US homes, WAP helps ensure that resources go where the need is. This approach stands in contrast to many utility efficiency programs that use funds from all ratepayers to primarily benefit middle-income households.

Weatherization and energy efficiency improvements through WAP can also improve health equity. Healthier buildings can help counteract the impact of the variety of factors that have contributed to racial and economic inequities, such as residential segregation, economic burdens, and extreme weather and climate impacts due to substandard housing.

ARRA Provides Three Key Lessons for Investing in WAP

Additional stimulus funding for WAP should build on past successes—while also expanding approved measures under the program, investing more in workforce development and diversity, and more thoughtfully allocating administrative resources.

- Expand approved measures under WAP: Measures should go beyond insulation, air sealing, and other efficiency actions to explicitly include electrification upgrades, such as heat pumps and induction stoves, given their indoor air quality and health benefits. Gas appliances are directly linked to health problems like asthma, which disproportionately affect low-income communities and communities of color. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention stated that people with moderate to severe asthma may be at higher risk of getting severely ill from COVID-19. Electrifying gas stoves and other combustion appliances can have meaningful health benefits for WAP beneficiaries, making their homes safer especially during prolonged periods when families are staying inside.

- Invest more in workforce development and diversity: ARRA funding increased the jobs supported by WAP from 8,500 in 2008 to 28,000 in 2010, but funding for WAP that comes in fits and starts makes building and sustaining a healthy workforce difficult. When this funding from ARRA ended, for example, WAP’s workforce and project pipeline rapidly contracted to near its pre-ARRA level. WAP funding should provide more sustained employment opportunities for its workers. For example, program administrators should be empowered to retain staff that can meet future demand for weatherization tasks that are currently on hold due to the pandemic.

Investments as part of WAP stimulate economic activity by creating domestic jobs, both in equipment/material manufacturing and installation. Last year, 2.38 million people worked in the energy efficiency sector—more jobs than in all of fossil fuel extraction. The COVID-19 pandemic has ravaged the industry, and hundreds of thousands of energy efficiency jobs have been lost since March. Efforts to strengthen the workforce should incorporate measures to improve workforce diversity. Numerous existing efforts train and equip youth, women, and/or people of color for jobs in the energy efficiency workforce. These include the City of Richmond, California’s RichmondBUILD Academy, Rising Sun Center for Opportunity’s Climate Careers program, Elevate Energy’s Contractor Accelerator, and RMI and Emerald Cities Collaborative’s Contractor Academy to name a few.

- Thoughtfully allocate administrative resources: ARRA led to a boom in weatherization, but there were several administrative barriers that received negative publicity. Surveys of state and local weatherization agencies during the ARRA period recommend allocating dedicated resources to cross-agency collaboration at the local, state, and federal levels to increase efficiency and align objectives and procedures across housing agencies, utilities, and other governmental agencies.For example, coordinating with the US Department of Health and Human Services to streamline funding and program delivery could yield greater impacts for both departments.

WAP’s federal and state program administrators should align the program’s resources and priorities with the goals and assets of communities. Including community members in the decision-making process can then improve the social and economic outcomes of the program. Many state and local agencies faced management, technical assistance, and media concerns as administrative burdens increased. About half of local agencies felt that the public’s support for weatherization increased generally, but they also reported low levels of public understanding of the program.

An Equitable and Sustainable Recovery

As part of the recent CARES Act, the federal government invested $900 million in the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP), which helps people pay their energy bills. LIHEAP allows 15–25 percent of funds to be reallocated to WAP at the state level. While this is commendable and contributes some funding toward weatherization, it is not sufficient to meet the need. Investing directly in WAP at multiples of the previous ARRA funding allocation would accelerate and scale housing improvements that sustainably reduce energy bills for those who need them most. It would also create domestic jobs, benefit public health, and improve racial and income equity in the long term.

Investment in WAP is an important part of RMI’s US Stimulus Strategy Recommendations report, which calls for this as part of a broader program that could accelerate residential and commercial building retrofits at scale.

We recommend significantly increasing funding to the WAP program while expanding the measures WAP undertakes and ensuring that the jobs it creates are sustainable and equitably allocated. This funding should be informed by the lessons above from ARRA to maximize economic, social, and environmental benefits, especially for communities of color.