Shot of a young man and woman wearing masks while travelling in a foreign city

Tackling NO2 from All Sources to Help Fight COVID-19

Common Pollutant from Vehicles, Buildings Linked to COVID-19 Death Outcomes

As the COVID-19 pandemic relentlessly creeps closer to claiming a million lives worldwide, it’s never been more important to understand what makes us vulnerable to the worst effects of the virus. While the risk factors of COVID-19 are still under extensive investigation, new research shows that air pollution plays a significant role in increasing our susceptibility to severe COVID-19 outcomes, including death.

Research published Tuesday in the Cell Press journal The Innovation is one of the first peer-reviewed studies on the relationship between air pollution exposure and COVID-19 death outcomes in the United States. Researchers from Emory University examined long-term exposures to three common outdoor air pollutants—particulate matter (2.5 microns or smaller: PM2.5), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), and ozone (O3)— from 3,122 US counties and assessed their impacts on severe COVID-19 death outcomes.

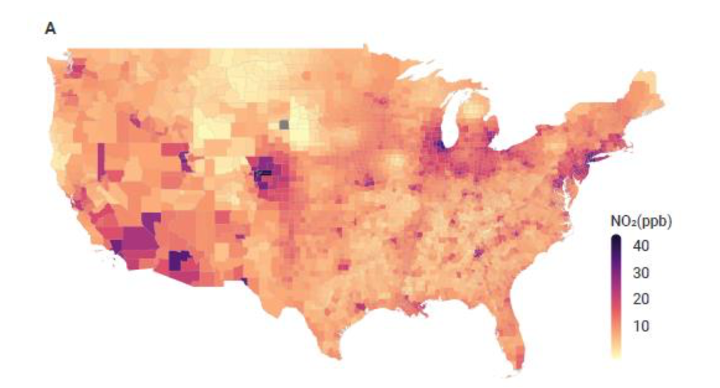

Of the pollutants analyzed, NO2 had the strongest independent correlation with raising a person’s susceptibility to die from COVID-19. NO2 is one of a group of highly reactive gases known as oxides of nitrogen or nitrogen oxides (NOx). NOx emissions are toxic gases on their own, but they also react with sunlight and heat to create dangerous ground-level ozone and secondary particulate matter.

Reductions in NO2 Could Save Lives

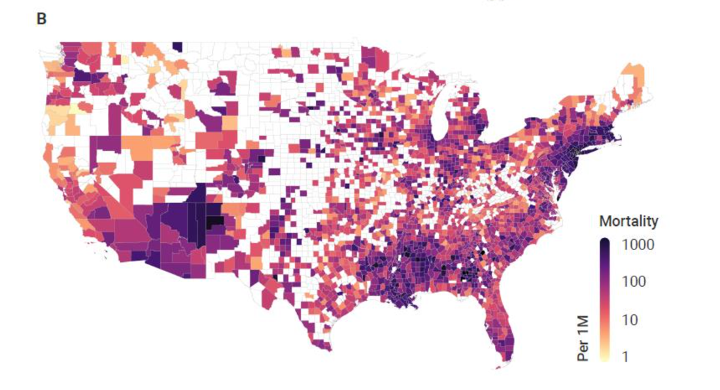

Researchers found that residents living in counties with higher levels of long-term NO2 were more likely to die from COVID-19. The highest NO2 levels were found in New York, New Jersey, and Colorado. In addition, the authors noted that people living in metropolitan areas of California and Arizona may be at higher risk, due to historically high NO2 pollution.

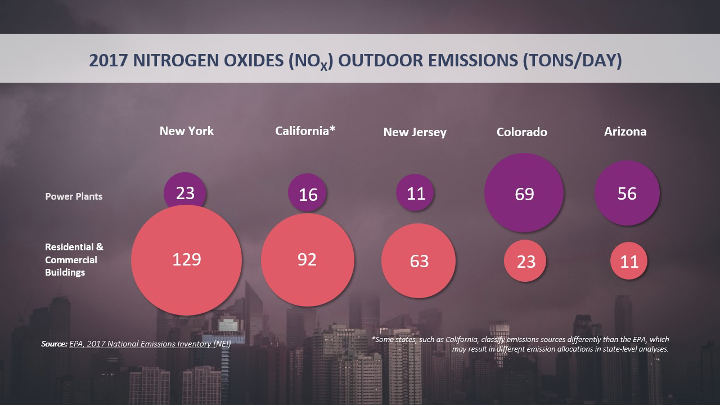

NOx is released from the burning of fossil fuels and is most strongly associated with transportation emissions. Although less than transportation, buildings and power plants are also significant sources of NO2 pollution, contributing to poor air quality in cities across the country. Buildings release NOx pollution when they burn fossil fuels in appliances—for example, gas water heaters and furnaces.

While power plant pollution has steadily decreased, thanks to a suite of air quality regulations, pollution from residential and commercial buildings has increased. A key reason for the increase is that indoor and outdoor pollution from buildings receives far less attention from policymakers than that from transportation or power plants.

One of the key study findings is that just a 4.6 parts per billion (ppb) reduction in long-term exposure to NO2 would have avoided 14,672 US deaths among those who tested positive for the virus, which translates to 44.7 avoided deaths per million US residents as of mid-July 2020. Outdoors, 4.6 ppb is a relatively small reduction. For comparison, a gas stove with a pilot light emits approximately 10 ppb more than a gas stove without a pilot light.

“Although average NO2 concentrations have decreased gradually over the past decades, it is critical to continue enforcing air pollution regulations to protect public health, given that health effects occur even at very low concentrations,” said Dr. Donghai Liang, assistant professor at Emory University and lead study author.

Nitrogen Dioxide’s Effects on the Body

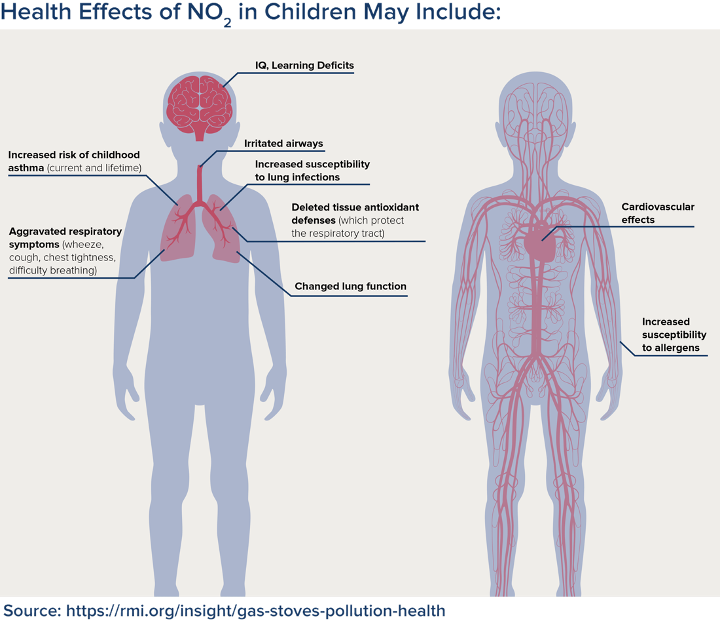

Breathing air with high concentrations of NO2 can irritate airways in the respiratory system and lead to coughing, wheezing, or difficulty breathing.

According to the American Lung Association, long-term exposures to NO2 can also lead to acute and chronic respiratory diseases. These include reduced lung function, increased risk of respiratory infection, increased asthma attacks, and a greater likelihood of emergency department and hospital admissions.

In 2016, the EPA found a causal relationship between short-term exposure to NO2 and respiratory health effects, such as asthma. For long-term exposure to NO2, the EPA found there is likely to be a causal relationship, based largely on evidence of asthma development in children. Some of the most susceptible populations to NO2 pollution are people with existing asthma, children, and the elderly.

The Risks of Indoor Air Pollution

While the Emory researchers focused on outdoor air pollution, the indoor environment is often unknowingly polluted with high levels of NO2. Even before the pandemic, 90 percent of our time was spent indoors. Now that people are home more than ever, it is critical to understand how the indoor environment interacts with health.

Gas stoves emit several pollutants, including NO2, that can be harmful to human health. We know from EPA data that homes with gas stoves have 50–400 percent higher concentrations of NO2 than homes with electric stoves. In addition to gas stoves, other sources of NO2 indoors include cigarette smoke, unvented gas or kerosene appliances such as heaters and woodstoves, and infiltration of polluted outdoor air. While the latest study analyzes COVID-19 outcomes in relation to outdoor air pollution, it is reasonable to also prioritize reducing indoor sources of NO2 pollution.

Air Pollution Is a Health Equity Issue

Additionally, the burden of NO2 pollution is not evenly shared. Poorer people and people of color often face higher exposure to pollutants and may experience greater impacts from air pollution, such as higher premature deaths and asthma attack rates. Nationally, NO2 exposure levels are 27 percent higher for low-income nonwhites compared to high-income whites. One study found that nonwhites experience 4.6 ppb higher residential outdoor NO2 concentration than whites—an exposure gap with potentially higher public health impacts.

A main strength of the Emory study was that it adjusted for co-pollutants and potential cofounding factors such as population density, socioeconomic status, race and ethnicity, behavioral factors, and county-level healthcare capacity.

Policymakers can utilize existing data to identify counties and urban centers with both high NO2 and highly unequal levels of this air pollution to prioritize environmental concerns. As evidenced by the most recent research on COVID outcomes, closing an exposure gap of 4.6 ppb could have saved thousands of lives.

Buildings Can Work for Us, Not against Us

Building emissions are much less regulated than power plants or cars and trucks. As such, new and better regulations on buildings represent a virtually untapped opportunity to reduce NO2 and other pollutants.

There are a few immediate ways to reduce building emissions:

- Though the EPA found strengthened evidence for the health effects of NO2, in 2018 the agency decided not to strengthen the 1-hour and 24-hour outdoor standards. The long-term standard has not been updated since it was created in 1971. Canada recently strengthened its outdoor standards and indoor guidelines of NO2 to some of the strictest in the world. Given the new evidence on COVID-19 and long-term NO2 exposure, a review and update to the federal standards should be prioritized.

- In the absence of federal action, cities can implement all-electric reach codes. These policies ensure that new buildings are constructed exclusively for electric appliances. To date, more than 30 California cities have committed to all-electric or mixed-fuel reach codes and cities in other states are joining the all-electric movement.

- Air regulators can require stricter emissions standards for gas appliances, like furnaces and water heaters. In California, Texas, and Utah air regulators have made progress on low and ultra-low NOx standards for these appliances, but more can be done. The most protective would be zero-NOx

- Stronger guidelines for indoor limits on NO2 and other pollutants are needed to protect public health. In the United States there are no federal standards or guidelines for indoor levels of NO2. Some states, like California, have guidelines but they should be updated considering the most recent evidence. The World Health Organization has indoor guidelines set in 2010, which are also due to be updated.

Evidence has been mounting that NO2 is a serious health concern. The latest linkage between long-term NO2 exposures and COVID-19 death rates add new urgency to find ways to reduce NO2 from all sources, indoors and out. In addition to electrifying transportation and reducing power plant pollution, buildings should be included in every mitigation plan. By committing to all-electric new construction policies and helping reduce air pollution across sectors, we can quite literally save lives.