Busy highway from aerial view. Guangzhou. China

Shenzhen: A City Miles Ahead

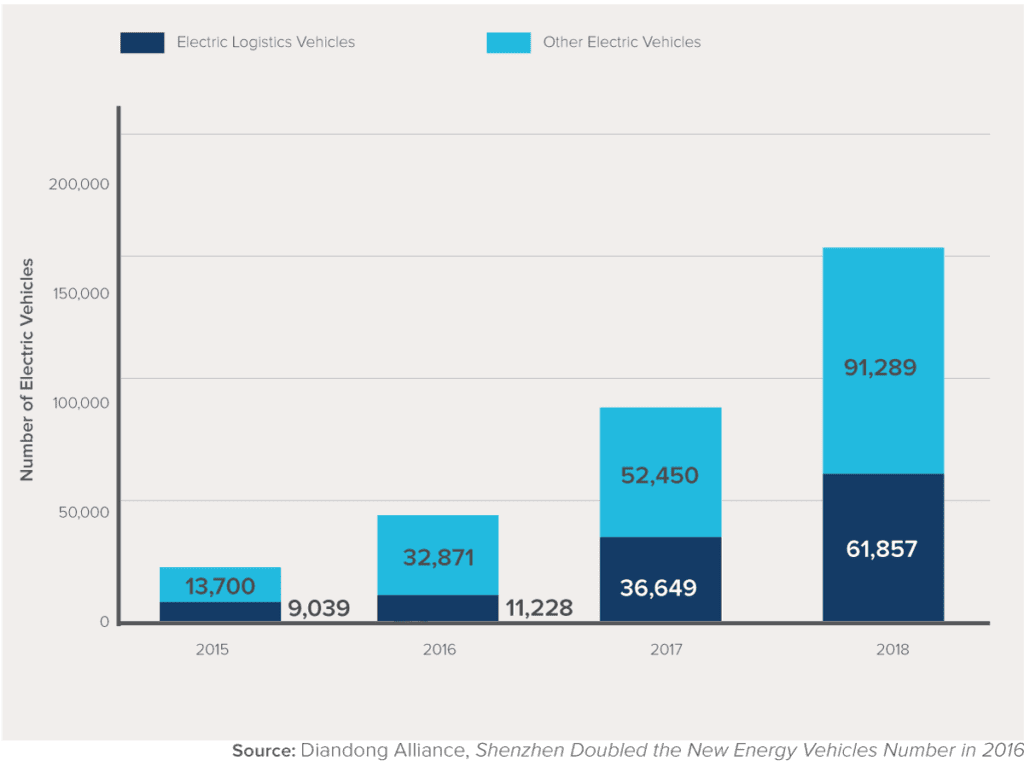

Two weeks ago, The Washington Post called Shenzhen, the tech hub in Southern China, a “pacesetter,” when reporting on how it became the first city in the world to turn nearly all of its buses and taxis electric. But it is not just public and for-hire fleets electrifying in Shenzhen. In the last three years nearly 60,000 electric light trucks and vans have been deployed for urban freight movement, representing approximately 35 percent of the city’s overall fleet of urban delivery vehicles.

RMI’s latest report, A New EV Horizon: Insights From Shenzhen’s Path to Global Leadership in Electric Logistics Vehicles, explores Shenzhen’s experience in the deployment of electric logistics vehicles and takes on one of the most important questions to accelerating adoption of EVs in urban delivery: how to effectively provide charging infrastructure. The analysis and conclusions are based on telemetric data gathered from electric logistics vehicles (ELVs) and a series of interviews with stakeholders, including charging station owners, logistics and leasing companies, and vehicle operators. We believe a deeper understanding of Shenzhen’s experience in ELV deployment can be a guidepost for other cities across the world aiming for a cleaner, low-carbon future.

Exhibit 1: Shenzhen Electric Vehicle Population 2015–2018

Shenzhen’s Innovative Policies Driving EV Adoption

Driving Shenzhen’s rapid growth is a novel portfolio of economic policies designed to make electric logistics vehicles an economically viable alternative to their fossil fuel counterparts. Shenzhen’s multipronged policy approach includes:

- Subsidies for electric vehicles, which create near cost parity between ELVs and internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles.

- Subsidies for charging infrastructure, resulting in rapid growth of a robust charging network.

- Road restrictions on vehicles with internal combustion engines, creating a strong incentive to shift to lower-emission delivery vehicles.

- Preferential electricity rates and fee exemptions for charging operators, providing ELV operators lower fuel costs.

- Mandates and targets at the city and district levels for the number of chargers to support growth of the charging network.

The effects of these policies are taking hold and the ELV market is seeing economies of scale in manufacturing and a resulting drop in prices. Shenzhen is now beginning to take its foot off the gas, reducing subsidies and allowing the market forces that they set in motion to take over.

Integrating Electric Vehicles into the Grid is a Key Challenge for Policymakers

The rapid deployment of electric logistics vehicles driven by economic policy has tested Shenzhen’s ability to provide sufficient charging capacity. The balance between charging demand and capacity is a challenge that policymakers, not just in Shenzhen, will have to overcome not only for electric vehicles to be scaled at the levels envisioned but also to support a clean transportation economy.

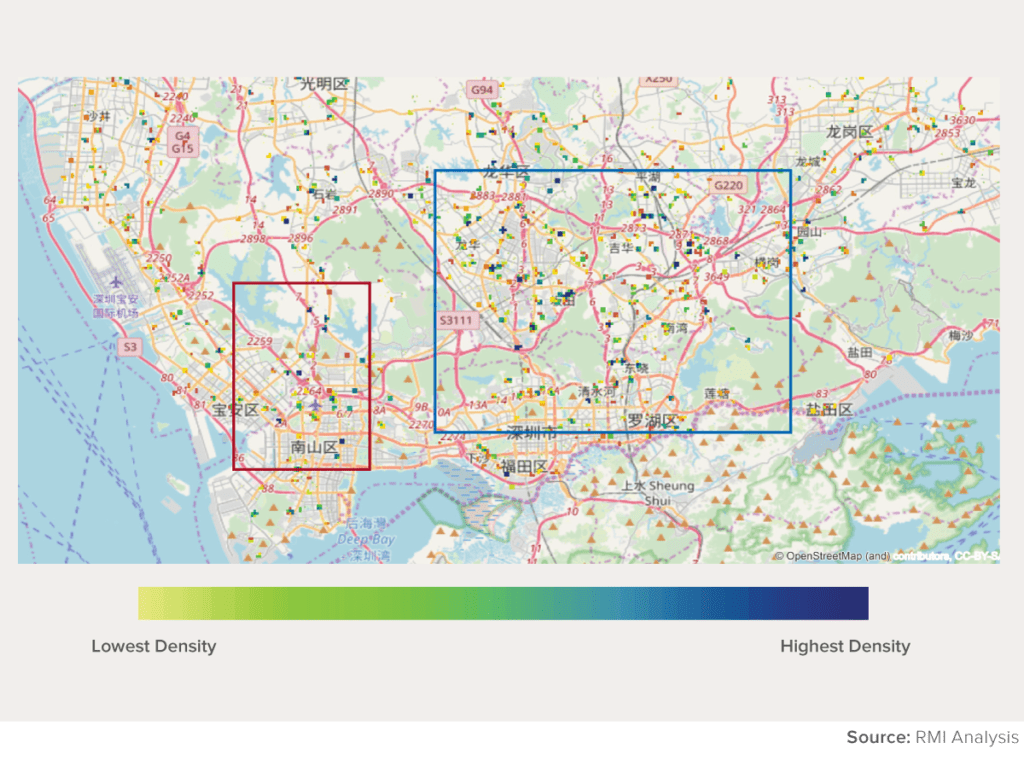

The most apparent of these challenges is a geographic mismatch between the demand for charging and current charging infrastructure. The areas that vehicle operators tend to work in are not the same areas in which they are able to charge. Figure 2 show the locations where ELV operators charge most often. This distribution displays a high density of chargers, marked by red and blue outlines, in the inner suburbs and logistics parks of large companies. Notably, the same logistics vehicles spend the bulk of their time delivering in the city center or parked overnight in the outer suburbs, making accessing charging stations inconvenient and inefficient. This kind of imbalance can be a deterrent for the further adoption of electric vehicles for logistics, an industry that requires efficiency.

Exhibit 2: Heatmap of ELV Charging Locations

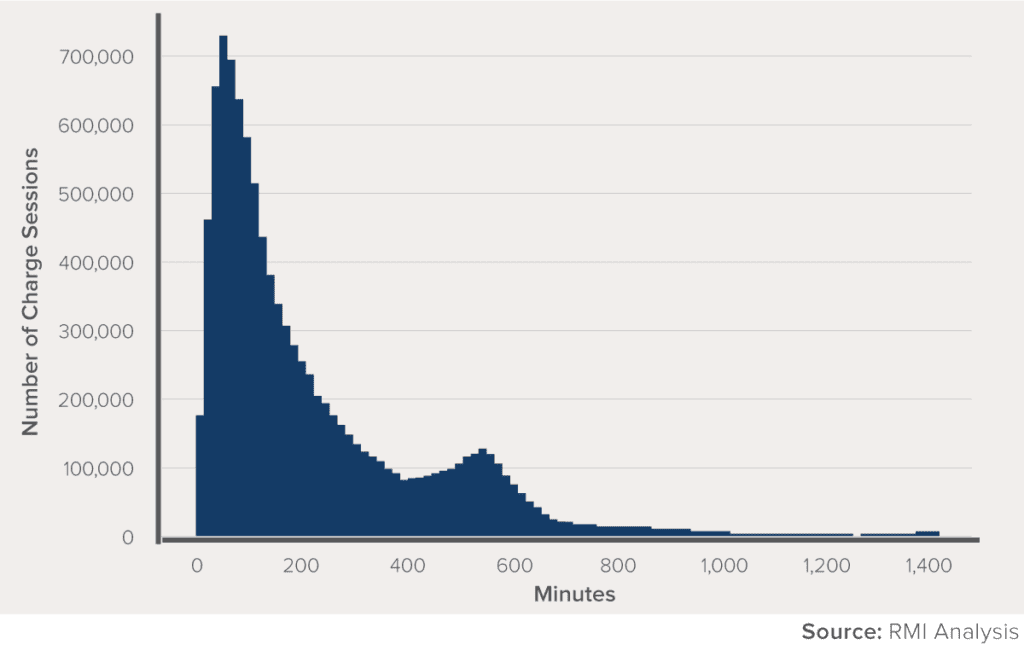

RMI has done an in-depth analysis of patterns of charging behavior in and around the city. One conclusion, vital to the growth of the electric vehicle market, is that the current charging preferences will eventually put pressure on the electricity grid in ways that it was not designed to handle. Figure 3 displays the distribution of charge duration across Shenzhen’s ELV fleet. The figure shows that vehicle operators in Shenzhen have a clear preference for shorter charging times, using “fast” chargers, which pull energy at a higher rate from the grid. Fast charging as the predominate means of charging can create unpredictable spikes in energy demand, something that electricity grids have difficulty handling. A grid unable to cope with the demands of a burgeoning clean economy may stand in the way of future growth. Without otherwise balancing charging supply and demand, other cities looking to scale up their electric fleets and clean up their cities will likely face similar hurdles.

Exhibit 3: Duration of ELV Charge Sessions

Digging into the Data

Data can play a crucial role in the design of urban charging networks by helping stakeholders understand their situation and how the decisions they make will affect that situation. Using an extensive set of telemetric data from Shenzhen’s ELV fleet, we were able to better understand the charging environment in Shenzhen. Through an in-depth analysis of this data, RMI identified a number of solutions to create a better charging climate and support further uptake of ELVs.

- Presently, it is the norm for city planning and electric vehicle data to exist independent of one another. If policy facilitated a better integration of data into these planning processes, the location of charging infrastructure could be optimized around areas of high demand and where the grid has capacity. Specifically, collocating charging with other establishments used by vehicle operators could provide convenient access to chargers.

- Current electricity pricing encourages charging practices that are unsustainable for the grid in the long run, as evidenced by the preference for fast charging during peak times of demand show in Exhibit 3. Using insights from the data, smarter strategies in electricity pricing could support a broader distribution of charging in time and space and create a more sustainable pattern of energy usage.

- Finally, as is the case in many locales, an authoritative, unified source of information on charging infrastructure is rare. The absence of such a source of information creates inefficiencies, such as the queueing that occurs outside charging stations in Shenzhen. Partnerships between data providers stands to benefit individual charging stakeholders and ease the friction that vehicle operators currently face when charging.

If policymakers are able to learn from and adapt these approaches to their own environments, they will find much less resistance to electric vehicle adoption.

Cities Can Lead the Way on Electrifying the Delivery of Goods

As cities across the world set ambitious targets to reduce emissions, they should consider the electrification of logistics vehicles as a critical element in their carbon-reduction strategies. Similar to taxis and public fleets, the higher utilization and faster capital recovery of logistics vehicles make a strong economic case for their electrification. Cities not only are perfectly positioned for the electrification of this goods movement due to their ability to make major transportation policy decisions, but they also have a serious incentive to do so. As the primary markets for the delivery of goods, cities feel the impacts of fossil-fueled transportation systems most acutely.

The road ahead for Shenzhen’s urban freight electrification is optimistic. The city has shown that it is willing to do what is needed to promote electric vehicle adoption. RMI’s research collaboration with the city is working to ensure that it can do the same for the supporting charging infrastructure. Shenzhen is not an isolated case. As cities become the leaders in the current energy revolution, they will increasingly face challenges similar to those Shenzhen is solving now. RMI believes that, with intelligent and careful research, these challenges can be surmounted, so that cities starting down their own roads to cleaner, low-carbon futures will find them much less bumpy.