People Are the Most Important Part of Regulation in the Decisive Decade

Public utility commissions (PUCs) across the country often lack the resources they need to regulate for an equitable, decarbonized future

With emissions on the rise as the nation rebounds from a pandemic-driven slowdown, the United States is dangerously close to missing its opportunity to mitigate the worst effects of climate change. In the coming years, action will be needed across every part of society to accelerate the transition away from fossil fuels and toward a clean, equitable grid. State public utility commissions (PUCs) and their staff will have a major role in this transition. These regulatory bodies are uniquely situated as the arbiters of utility decision-making and have immense influence over how utilities invest and operate.

In our second insight brief on PUC modernization, we explore how PUCs’ internal organization is evolving to match emergent industry and society needs. PUC workloads are increasing due to new state policy requirements and an expanding scope of policy priorities that regulators must consider—including decarbonization, equity, and environmental justice. Drawing on expert interviews and research, our brief identifies common challenges facing PUC commissioners and staff across the nation. Across the board, we find that many commissions have been challenged to balance rising workloads with limited staff, limited resources, and growing gaps in internal expertise due to the increasingly specialized needs of today’s energy system.

Position Commissioners to Lead the Energy Transition

As PUCs grapple with their expanding roles in the energy transition, commissioner roles are also evolving. Twenty-four states plus Washington, D.C., now have laws on the books directing the utility sector to decarbonize and reduce its emissions—though only a handful have explicitly expanded their PUC statutory mandate to prioritize emissions reduction alongside traditional regulatory objectives.

Without clear expectations about their role in the energy transition, some commissioners in these states may hesitate to take bold steps to accelerate progress, because PUCs face ambiguity as to how the PUC weighs emissions reductions against other regulatory objectives. In a recent decision, the New York Public Service Commission (PSC) determined that the state’s climate law applied to how commissioners made decisions in rate cases. However, the PSC also emphasized that it lacked guidance on how state agencies should address potential tensions between mandated emissions reductions and the PSC’s core mandate to ensure safe, adequate, and reliable service, and the obligation to provide service where feasible.

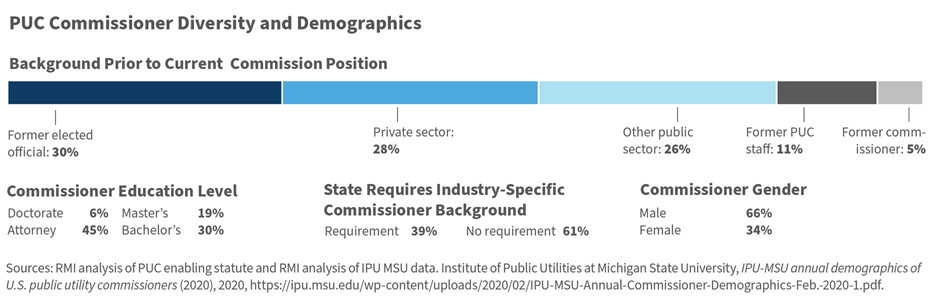

This lack of clarity about PUC roles—plus the fact that many commissioners start their jobs without legal or industry-specific expertise—may result in passive regulation (e.g., accepting proposals in proceedings without up-front framing or independent analysis). However, the scale and complexity of the energy transition demands proactive regulation to identify and address emerging issues. Across the United States, less than half of commissioners have a background in an industry they will regulate. While industry experience is not the only desirable quality in a commissioner, those with minimal experience on critical issues (e.g., the economics of clean energy) may face steep learning curves that make it more challenging to lead on timely regulatory issues.

States have taken various steps to position commissioners to lead. In Connecticut, there are codified prerequisites that indicate qualifications commissioners must have to be considered for the position. Oregon law empowers any employee within the commission to propose a change to any staff role at the PUC, and charges commissioners with reviewing and approving any proposed changes.

Improve Staff Organization

Even commissioners with relevant prior experience and a clear sense of their roles and responsibilities may find themselves ill-equipped to immediately tackle the many and fast-changing issues of the industry—particularly those that relate to new and emerging policy priorities. This gives the 8,000 employees working in PUCs across the country significant influence to shape regulatory decisions by contributing their expertise. Commissioners must particularly rely on these technical and research staff when making decisions on issues where it would be impractical for an individual to quickly become an expert.

However, commissioners and staff we interviewed for the insight brief cited common structural challenges that get in the way of collaborative commissioner-staff working relationships. Among other challenges, interviewees identified issues when commissioners do not have access to dedicated commission staff, or when an overarching decision-making framework is lacking for staffing or project allocations. For example, commissions often need to decide between allocating staff to traditional regulatory tasks or to more nascent or innovative regulatory topics. These challenges can be exacerbated when commissioners and staff have different views on the needs and direction of the commission.

While there is no one-size-fits-all solution, certain internal reforms can lessen the impact of these issues. For example, the Colorado PUC has a Research and Emerging Issues Unit within its staff, which guarantees that at least some staff are able to work on emerging issues the commission may be facing, in addition to the PUC’s day-to-day demands. Other commissions lean on executive director or advisor roles to make staffing decisions and ensure project timelines are managed. Still others have begun giving commissioners dedicated staff to increase opportunities for collaboration and ensure they have access to needed research and advice.

Increase PUC Resources to Meet Industry Needs

The flurry of legislative mandates aimed at the utility sector are stretching PUCs thin. They must balance the demands of these new requirements and regulatory frameworks against the commission’s routine business, such as rate case approvals and planning decisions. This has resulted in commissions being understaffed and under-resourced. Further, not all commissions have the knowledge base among their staff to make informed decisions on an ever-expanding regulatory scope.

To solve some of these issues, legislatures can ensure PUCs have access to funding for new employees, or access to external support on new policy objectives. Some states, like Colorado and Oregon, have been approved to hire external consultants to assist on a topic-specific basis. New York recently took a different route and approved expanding the number of commissioners from five to seven “in light of the numerous expanded responsibilities and initiatives tied to the energy transition.” PUCs themselves can try new hiring practices or leverage support from programs like the Solar Energy Innovators Program to get early-career talent in the door. After that, commissions must work from the inside out to ensure new employees feel valued, are supported appropriately, and have avenues to succeed.

The People Dimension

Without the right commissioners and staff—or the structures and resources to support them—PUCs may face insurmountable challenges as they attempt to orchestrate the energy transition. RMI’s insight brief explores how PUCs can be modernized to meet industry needs and unlock innovative decision-making. As we come face to face with climate change, it has never been so important that commissions have the talent and resources they need to regulate utilities as critical drivers of decarbonization.