A Utility Business Model That Embraces Efficiency and Solar Without Sacrificing Revenue?

A few weeks ago the city council in Fort Collins, Colorado, unanimously voted to accelerate the city’s climate action goals to achieve an 80-percent reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2050. The municipally owned Fort Collins Utilities understood the community’s desire for such aggressive action, which will be critical to the success of the effort, and has taken steps to better understand the utility’s role helping the community meet its energy transformation goals. One of those steps was working with RMI.

At first glance it may seem as though the utility’s revenue is doomed to plummet—among other elements, the city’s approach calls for a rapid scale-up of distributed renewables and building efficiency—but an exciting innovation suggests otherwise: the integrated utility services (IUS) model. The IUS utility business model that RMI developed for Fort Collins Utilities: a) deploys energy efficiency and rooftop solar as default options for residential and small commercial customers, b) does so with on-bill financing and other mechanisms to ensure no increase in customers’ monthly utility bills, and c) preserves utility revenue. This sounds like an unlikely, too-good-to-be-true combination, but our analysis shows that both municipally-owned utilities like Fort Collins Utilities and other member- or independently-owned utilities alike can achieve very real success.

Here’s how the IUS model came about. In the fall of 2012, RMI published Stepping Up in partnership with Fort Collins Utilities, which assessed the costs and benefits of accelerating the community’s greenhouse gas emissions reductions targets. The Fort Collins of that future would look very similar to today: beautiful old historic buildings, respectfully renovated to become more energy efficient; parks and open spaces with more trees and more expansive biking and walking trails; empty lots developed with transit-oriented, multi-use buildings. But such a future would also be fundamentally different. In order to hit such aggressive emissions reduction goals, the majority of the ways citizens consume energy (e.g., when driving their cars, heating their homes, and powering their buildings) would need to be electrified. In tandem, the electricity generation mix would need to shift from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources, such as utility-scale wind, distributed rooftop solar, and storage.

The electrification of the energy system would have large implications for the utility, including changes to traditional electricity demand—our research suggested a 31-percent decrease in building energy use and almost 320 MW of distributed solar on customers’ roofs. And it would imply the emergence of new, non-traditional demand—our research also suggested that electrification of almost 50 percent of passenger vehicles and a switch to non-gas heating sources for one in three homes would be required.

Given the large changes the utility and its customers would have to make, Fort Collins Utilities approached us with a second set of questions that we think utilities of all stripes should consider:

- How can a utility help most of its customers participate in the energy transition (by investing in efficiency, distributed solar, or other opportunities)?

- How can a utility roll out these new services without disrupting or destroying its own revenue?

RMI, with the support of an e-Lab working group, the Colorado Clean Energy Cluster, and Fort Collins Utilities, set out to answer these questions through the design of a new utility business model.

THE UTILITY BUSINESS MODEL OF THE FUTURE

The first conclusion we reached was that expanding the area of a utility that typically delivers efficiency and distributed solar programs (known as an energy services program) would be inadequate. To reach mass adoption, we wanted to start with a clean slate. The utility would need to seamlessly weave together various products, services, and financing tools that had never been integrated, and do so with an eye towards supporting revenue in the way it has with traditional electricity sales. This business model would help customers access a broader range of energy services—including efficiency improvements, distributed renewables, transport and heat system electrification, and demand response—in one comprehensive package, with monthly payments on the electricity bill. This integrated utility services model—the IUS model—could, if designed correctly, align a utility’s interest in its financial health with the interests of customers who want to invest in efficiency and distributed solar, and make these investments appealing to a wider range of customers.

Key program features would include:

- A package of basic efficiency and distributed solar offerings that, when financed on a customer’s bill, do not increase monthly costs

- An integrated intake and service-delivery experience for customers

- A platform that allows for new services to be offered over time (and for innovative partners to participate in such offerings)

- An on-bill financing program that would leverage diverse sources of capital

Here’s how the program we developed could work. The utility would contact customers to notify them of the new program and the options available for their home energy goals. An experienced third-party provider would contact customers and walk them through a set of choices for a bundle of services customized to their home. Contractors would then conduct audits and install measures in one fell swoop, keeping installation and procurement costs low. With high customer adoption and bundling offering a sort of “mass customization,” the utility could likely achieve economies of scale that would lower costs even further. Billing, quality control, monitoring and verification, and reporting would continue to be managed by the utility to ensure program success. Customer bills would reflect energy cost savings netted against service charges for the improvement measures. As the program delivered results, customers could consider upgrading for additional services such as new windows or a new refrigerator. Figure 1 shows one option for how services, energy, and cash would flow in such a program.

THE BOTTOM LINE

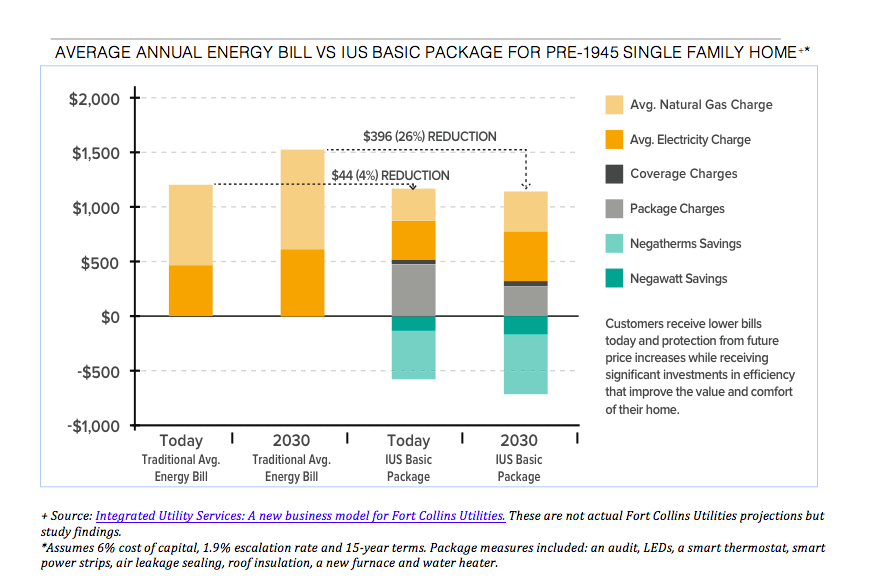

Our initial analysis shows customers could reduce their bills by roughly five percent when participating in the program’s basic, bill-neutral package. Since the customers’ service charges, like power purchase agreements, need not escalate as fast as utility pricing (or at all), these savings could rise substantially over time, to as much as a 25-percent bill reduction by 2030, according to one projection we ran (see Figure 2).

Meanwhile, utility income could increase, as these services, many of which continue to experience technology-driven cost reductions, are likely to be more profitable than traditional sales of electricity. There is also room to sell new services (just as some utilities are now offering high-speed Internet).

Our analysis, using public data, of Fort Collins Utilities’ revenue projected over the next 15 years shows how a utility’s balance sheet might be affected. We compared a business-as-usual (BAU) case with an IUS case. The IUS case includes at least a 60 percent adoption rate of the basic package, as well as a 10 percent additional adoption of premium offerings. Depending on the program’s financing structure, Fort Collins Utilities’ annual revenues in 2030 could remain roughly constant, even as overall kWh sales decline. But crucially, revenue net of costs can remain stable (or even increase if this was the goal).

While the utilities and individual customers would do well, the community would see tremendous gains. If 60 percent of the Fort Collins residential market segment participated in a basic package and 10 percent chose to upgrade to additional services (things like energy-efficient windows that might come at a cost premium but deliver great energy savings), Fort Collins’s greenhouse gas emissions could drop by more than a half-million metric tons per year. These reductions would achieve 32 percent of what RMI showed was possible across all sectors (electricity, buildings, and transportation) in the Stepping Up report. It would also help customers access 195 MW of distributed-renewable generation capacity by 2030.

LOOK TO THE VANGUARD

In the face of declining overall electricity sales, even publicly traded utilities should explore options like this. Concern abounds in the energy industry about the “utility death spiral,” the phenomenon where utilities’ revenues are eroded so dramatically by the adoption of distributed energy resources that they find themselves forced to raise their rates continually, causing energy efficiency and renewables to become that much more cost competitive, further exacerbating utilities’ top-line erosion. But some industry players see the advent of a new era. Publicly traded independent power producer NRG’s CEO, David Crane, wrote in a letter to share holders:

There is no energy company that relates to the American energy consumer by offering a comprehensive or seamless solution to the individual’s energy needs… that connects the consumer with their own energy generating potential… that enables the consumer to make their own energy choices… that the consumer can partner with to combat global warming without compromising the prosperous “plugged-in” modern lifestyle that we all aspire to… NRG is not that energy company either, but we are doing everything in our power to head in that direction… as fast as we can.

Just recently, NRG partnered with Green Mountain Power in Vermont to offer products and services ranging from micropower for residential consumers (a package of renewable generation, water and space heating, and storage) to electric vehicle infrastructure programs for the state. Simultaneously, companies such as Next Step Living, CLEAResult, and Snugg Home seek to create energy-concierge services that provide an interface between utilities, their customers, contractors, electric vehicle dealerships, and lending agencies.

THE WAY FORWARD

Utilities have an incredible opportunity in the IUS model and related approaches to leverage their direct access to energy customers and provide them with the very products that are traditionally viewed as a threat. While it will require establishing more nuanced billing and banking systems, among other capabilities, these challenges are not insurmountable. In fact, in many ways that is exactly what competitors such as SolarCity do well. Utilities have predominantly viewed their energy-services departments as money pits, administering cumbersome efficiency and rebate programs. But perhaps it’s time to circle back and take a fresh look at the activities and services these departments know so well. After all, those services could be utilities’ biggest hope for the future.

Image courtesy of American Spirit / Shutterstock.com