Curved road trough the forest. Pass in Transylvania, Romania. Aerial view from a drone.

Charting the Course to Climate-Aligned Finance

As the world comes to grips with the magnitude and speed of the economic transition needed to avert catastrophic climate change, the vital role of finance is coming into focus. Nowhere is this more apparent than in recent climate commitments by major financial players: within the last two years, financial institutions representing $17.2 trillion have committed to align their portfolio emissions with the temperature goals of the Paris Agreement.

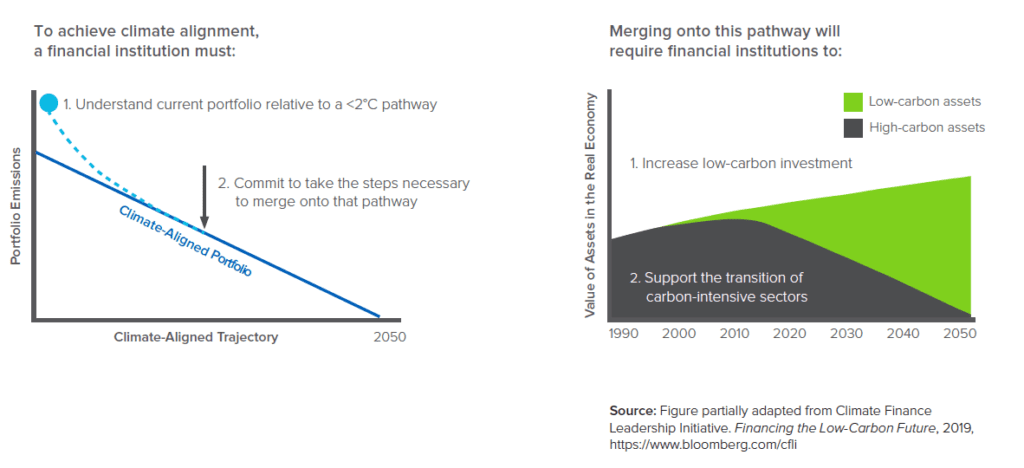

The idea is elegant in its simplicity: to achieve climate alignment, a financial institution must (1) understand the climate impact of its current portfolio and investment strategy in relation to an emissions pathway consistent with a <2°C future, and (2) commit to take the steps necessary to merge onto that pathway. However, while the concept may be simple, for mainstream financial institutions, implementation may be more complex.

With momentum behind climate alignment increasing, the scale of ambition is impressive. But the question remains: how can banks and other financial institutions actually meet climate alignment commitments, and will these commitments result in real emissions reductions?

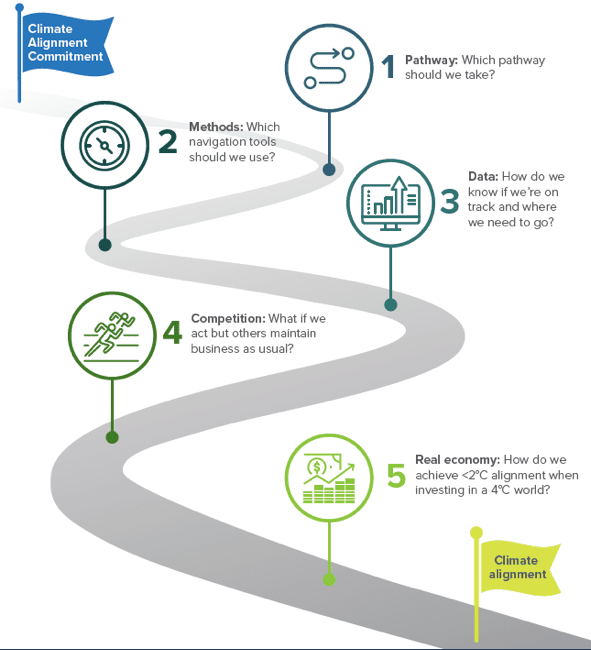

RMI’s latest report, Charting the Course to Climate-Aligned Finance, offers key insights for financial institutions on their journey to climate alignment. It lays out five common barriers banks, asset managers, asset owners, and other financial actors may face when considering alignment and how a sectoral approach can help.

Five Common Barriers to Climate Alignment

While financial institutions aren’t monolithic, with each facing its own particular set of challenges, there are five common barriers that make climate alignment difficult to deliver:

Barrier 1: Choosing between multiple decarbonization pathways

As financial institutions chart out the climate impact of their current portfolio and investment strategy in relation to a <2°C pathway, they must identify a decarbonization pathway to guide investment decisions. Choosing a pathway requires making some assumptions about what the future will look like—which types of clean technologies will be available and at what cost? On what timeline must fossil fuels be phased out in different sectors? With countless permutations of assumptions, the pathways to well-below 2°C are nearly limitless and sometimes contradictory. The latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) profiled no fewer than ninety 1.5°C pathways. By choosing one pathway over another, a financial institution not only locks in a specific set of investment opportunities, but also may be vulnerable if a regulator chooses a different pathway to enforce.

Barrier 2: Navigating varying methodologies

A financial institution must also select the methodology it will use to measure progress toward merging onto a decarbonization pathway. Here too, varying tools and methodologies have emerged from a proliferation of initiatives, from approaches that calculate the carbon footprint of a portfolio to others based on various technology or emissions scenarios. Each approach has its own benefits or drawbacks in terms of transparency, flexibility, data needs, comparability, or ease of implementation—all of which need to be understood and navigated by a financial institution.

Barrier 3: Sourcing adequate data

Sourcing high-quality, decision-useful data to plug into climate alignment methodologies can also be challenging, especially where data is proprietary, inconsistent, or altogether unavailable. While voluntary reporting initiatives have made tremendous progress in mainstreaming corporate climate data disclosure, comprehensive emissions reporting is not yet standard practice across all industries and geographies. Of the companies included in the MSCI World Index, which represent about 60 percent of global market capitalization, just under half report their GHG emissions.

Barrier 4: Overcoming competitive disadvantages

Once armed with robust targets, methods, and data, first movers that embrace climate alignment face the possibility of losing clients and investment opportunities to competitors in the short term. Additionally, financial institutions that simply reallocate capital to green their portfolio, are not necessarily reducing emissions in the real economy due to emissions “leakage.” A single financial institution, even with several trillion dollars in assets under management, cannot move the $80 trillion in the global economy alone.

Barrier 5: Influencing the real economy

Even after navigating these challenges, financial institutions still face their biggest barrier: achieving <2°C alignment when investing in a 4°C world. Despite growth in green asset classes in recent years, total sustainable investment remains only a small fraction of the larger financial sector. Faced with a limited universe of climate-aligned investment opportunities, a large financial institution that wishes to align its portfolio or loan book with a less than 2°C pathway would find it impossible today. For example, French insurer AXA has already eliminated coal and oil sands assets from its investments and business relationships, and aims to achieve a climate-aligned portfolio. However, the Head of Climate and Environment at AXA has shared the sobering reality that the company would need to divest all of its top 100 corporate holdings in order to achieve a portfolio aligned with 1.5°C.

The Way Forward: A Sectoral Approach to Climate Alignment

Rather than trying to overcome these barriers across the entire global economy, tackling climate alignment sector by sector offers a more efficient, pragmatic, and effective way forward. Specific industry sectors, such as power generation, shipping, aviation, or steel production, each have their own distinct political economies, technological and business model decarbonization pathways, and data challenges. A sectoral approach helps break down challenges into more manageable pieces and brings the locus of problem-solving to the relevant level. Approaching alignment through a sector lens—and with the input from stakeholders in that sector—can reveal realistic decarbonization pathways and fit-for-purpose methodological and data solutions that might otherwise get lost through a more generic whole-portfolio approach.

Sectors also often have distinct financing arrangements, with each relying more or less on different sources of capital to fund their activities. By understanding where capital sources are concentrated in a given sector, financial institutions can focus efforts on mobilizing a targeted coalition of financial actors to collectively drive change. A case in point of this approach is the Poseidon Principles, a first-of-its-kind climate alignment framework for the maritime shipping industry, which was successfully crafted by engaging a concentrated community of commercial lenders for ship finance. Such sector-specific strategies can ultimately be part of a more holistic framework that systemically guides financial institutions’ overall strategies.

While finance cannot single-handedly decarbonize the real economy, private financial institutions across the investment chain can—and, as worsening climate impacts and rising public expectations suggest, must—play a role in the low-carbon transition. As demonstrated with the Poseidon Principles, financial institutions armed with a clear decarbonization pathway, robust data and methods, and an effective coalition, will have the tools they need to overcome these challenges and increase momentum for the transition of assets in the real economy.

Read the full insight brief on barriers to climate alignment.