Stressed and helpless man at home worrying about the high bills. Inflation concept

Large Energy Users Want Power. Here’s How to Protect Other Ratepayers from the Costs.

Designing large load tariffs with strong safeguards can reduce the risk of cost shifting, but adoption of them varies.

Across the United States, alarms are sounding that surging demand from new large electricity users, especially data centers, is driving up costs for everyone else. With utilities planning to invest billions of dollars of investment in the grid to serve these new large loads, there is a growing risk that these costs could spill onto others in unfair ways.

One way that regulators are seeking to manage this spillage is by developing or updating large load tariffs that define the electricity rates and terms of service for these customers. Utility rate design is centered around the question, “How should we have customers pay for the costs to serve them?” To do this, utilities group customers with similar usage patterns or service needs into rate classes. Large load tariffs legally establish a distinct rate class for large energy users and define the conditions they must accept to receive service. Because tariffs are flexible legal structures, what they can achieve depends entirely on how they’re designed.

Over the past year, utilities and regulators have been updating or designing large load tariffs to include more terms that “safeguard” or help shield ratepayers from the costs and risks of large load additions that could drive up rates. This article explores what some of the most common safeguard provisions are and how they are being adopted in a review of 65 state-level tariffs across the country.

The data used in this article is sourced directly from Halcyon, a deep research software platform that uses AI to make it easy to find and analyze energy information. Halcyon’s Large Load Tariff Tracker provides regularly updated state-level market intelligence on how utilities are engaging with data centers and other large load customers.

How eligibility is defined in large load tariffs

The first step in designing a large load tariff is determining who it will apply to. Utilities typically determine which customers fall within the rate class established by the large load tariffs based on a set of eligibility criteria.

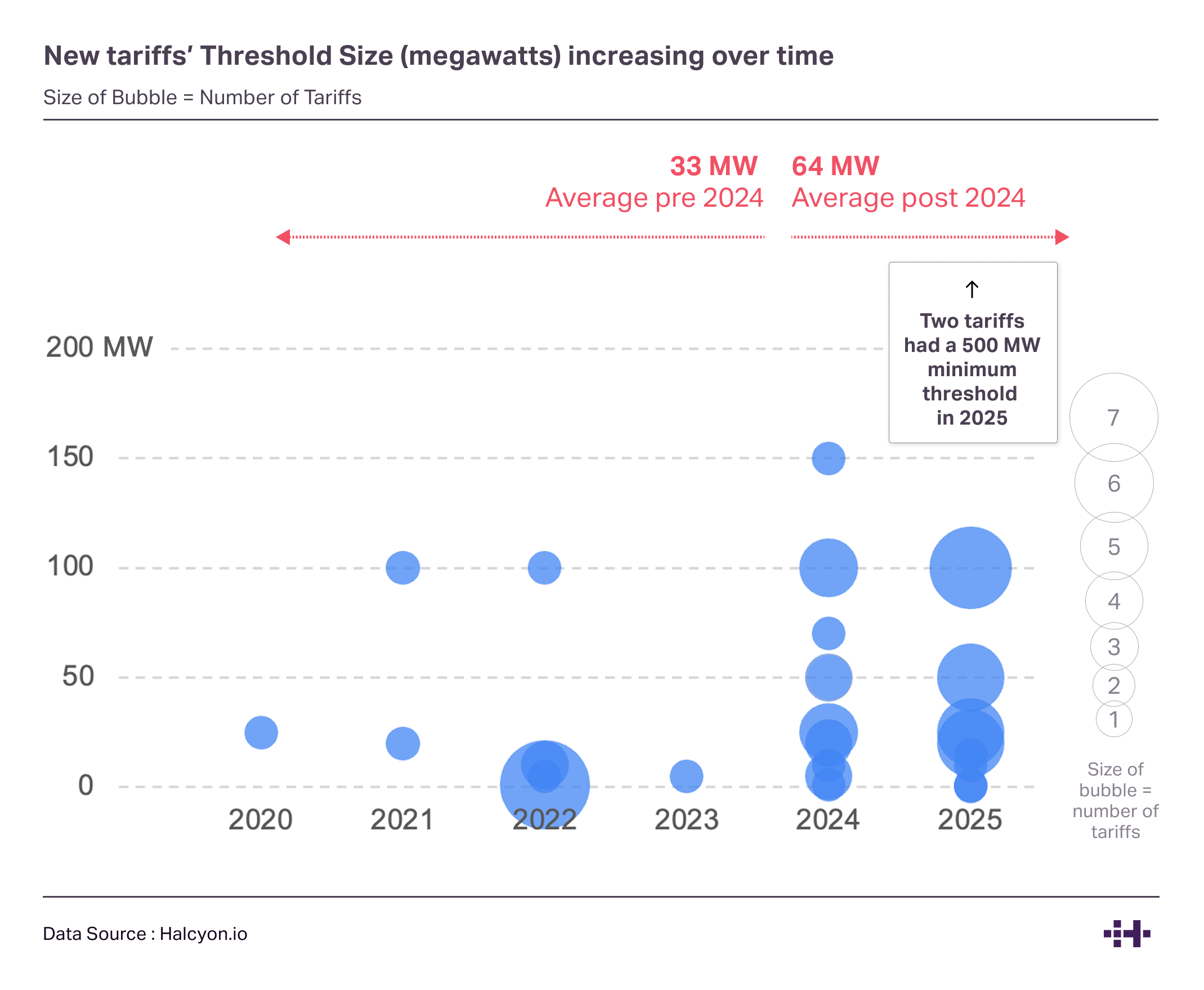

The most common way to define eligibility of a large load is by its total capacity in megawatts. As shown in Exhibit 1, over the past few years large load tariffs have begun to more frequently set higher threshold sizes, although the “right” size will likely vary by system. Many large load tariffs that set eligibility by size also include aggregation clauses to prevent customers from splitting a large facility into smaller loads on nearby sites to avoid falling under the tariff. Other criteria that are sometimes used to establish large load tariff eligibility include load factor, power factor, or industry. In some cases, lawmakers will legislate these thresholds themselves or direct utility commissions to set them, as in Utah’s SB132, which defines large loads as those 100 MW or greater, and Minnesota’s HF16, which directs the Public Utilities Commission to establish an appropriate threshold for a new large load rate class.

Simply establishing a separate rate class for large energy users can play a role in safeguarding other customers and set the foundation for fair cost allocation. It does this by providing more transparency into what it costs to serve these large load customers and the revenue they contribute.

Exhibit 1

Five common large load tariff terms designed to protect ratepayers

To keep other customers from footing the bill for infrastructure built to serve a large energy user that never materializes or exits early (i.e., a stranded asset risk), and protect from unfair cost shifting, large load tariff designers are increasingly integrating the following safeguards:

- Minimum Contract Term

Minimum contract terms can ensure the large load customer remains committed to stay on the system and continues to pay for the infrastructure required to add them to the grid. Longer contract term lengths can better align the cost recovery period of long-lived grid assets with the large load’s financial commitments.

Across the 65 tariffs reviewed, large load tariffs feature minimum term lengths ranging from 1 to 20 years, and longer term lengths have become more common in recent proposals, shown in Exhibit 2. An example from the higher end of this trend is Kentucky Power’s recently approved Tariff Industrial General Service, which sets a 20-year minimum contract term for all new loads of 150 MW or more. However, it is unclear if this includes a “Load Ramp Period.” In some cases, the minimum term begins only after a “Load Ramp Period,” which is a few years where the customer gradually increases their demand to reach the contracted size.

Exhibit 2

The longest minimum contract terms (20 years) still fall short of most grid asset lifespans. When a large load’s contract ends, significant remaining infrastructure costs might then fall to other customers. Regulators, utilities, and policymakers will have to continue to evaluate whether that risk is balanced against the benefits of rates that attract customers.

- Minimum Monthly Billing Demand

Another common ratepayer protection emerging in large load tariffs is minimum monthly billing demand. This feature sets a level of demand a large energy user is required to pay each month, even if they use less. The minimum monthly billing demand can reduce the risk of large loads not contributing their fair share of system costs if they’ve been too bullish about how much power they need, and can encourage large load customers to more conservatively estimate their capacity.

Large load tariffs currently use a variety of formulas to establish the minimum monthly billing demand. The three most common ways large load tariffs to date are setting this minimum is with a percent of the customer contract capacity (often 75–90 percent), the customer’s historical peak, or a fixed floor. As shown in Exhibit 3, many tariffs use a combination of these mechanisms (“hybrids”) and require that large load customers pay for whichever is greater. The customer’s highest level of demand, or historical “peak,” is measured in different ways across tariffs.

For example, Indiana Michigan Power’s Industrial Power Tariff sets the minimum monthly billing demand as the greater of 80 percent of the capacity contracted by the customer, or 80 percent of the customer’s highest monthly demand over the prior eleven months.

Exhibit 3

One design consideration is that minimum monthly billing demand efficacy relies largely on the rate of the demand charge ($/kW of billing demand). If the demand charge does not sufficiently reflect what it costs to serve large load customers, this provision may be less effective at mitigating the stranded asset risk to other ratepayers.

One stakeholder concern is that minimum billing demand provisions might make flexibility or efficiency less appealing to large load customers once they’ve signed a contract. However, there may still be opportunities to incentivize those behaviors up front at the planning stage, before utilities incur costs to build capacity.

Beyond minimum monthly billing demands, some large load tariffs also set a broader monthly billing floor that covers multiple cost components and service riders beyond just demand. These are often referred to as minimum charges.

- Collateral Requirements

Thirty-seven of the tariffs reviewed included collateral requirements. Collateral requirements in large load tariffs help protect other ratepayers by ensuring large loads can cover costs like unpaid bills, exit fees, or penalties if they default or leave their contract early. In essence, these requirements can be designed to reduce the likelihood that stranded costs or solvency issues are passed on to other customers.

Common forms of collateral in large load tariffs reviewed include:

- irrevocable letters of credit from banks,

- cash deposits, or

- guarantees from financially strong parent companies or affiliates.

In the tariffs reviewed, a common range for collateral requirements was 12 to 24 times the customer’s largest monthly bill or estimated minimum charge. However, some used a dollar per megawatt approach. For example, Dominion Energy’s GS-5 Large General Service Tariff requires $1.5 million in collateral per megawatt of contracted capacity. This collateral can be posted in the forms described above. This requirement can be reduced up to 70 percent for customers with sufficient credit standing or liquidity. A few large load tariffs have also tied collateral requirements to the full cost of certain infrastructure built for the large load.

- Exit Fees

Thirty-one of the tariffs reviewed included exit fees. Exit fees can be designed to discourage large load customers from leaving their contract early or overestimating their capacity needs. If they leave early, default, or significantly reduce their capacity, these fees can help cover the costs the utility has already incurred to serve them. Exit fees are often tied to other parts of the tariff like notice requirements, collateral rules, contract length, or capacity reassignment allowances. For example, AEP Ohio’s Schedule Data Center Tariff allows the customer to terminate the contract for a fee equal to 36 months of minimum charges, but only after five years in the contract and with three years of advanced notice.

- Capacity Reassignment

Twelve of the tariffs reviewed included capacity reassignment as a safeguard. Large load tariffs can allow a customer to transfer part or all their contracted capacity and financial responsibilities to another qualified customer if they no longer need it. For example, Appalachian Power Company and Wheeling Power Company’s Schedules L.C.P. and I.P. allow customers to reassign or reduce up to 20 percent of their contracted capacity without penalty under certain notice and term conditions. Under the tariff, the utility must try to reassign the capacity for any reduction requests beyond 20 percent and requires exit fees from the customer. This can protect ratepayers by creating an opportunity for another large customer to pay for costs incurred and use the grid capacity, limiting stranded assets.

Some of the large load tariffs reviewed reduce or waive exit fees when the departing customer finds a successor, creating an incentive to line up replacements. When paired with other protections, capacity reassignment can support large loads to adjust to changing business needs, conditions, and innovations, including those in efficiency and flexibility.

Transforming large load growth into a driver of reliability and innovation

The protections outlined above have the potential to be valuable mechanisms to mitigate the impact of large-load-driven costs and risks on other ratepayers. While these five safeguards have emerged in tariffs filed today, as more large load tariffs are developed, regulators and utilities can continue to innovate and explore types of provisions that further protect ratepayers.

Safeguard provisions in large load tariffs are only one tool to protect ratepayers. Reducing the need for system expansion by harnessing flexibility, refining cost allocation methods to reflect the benefits ratepayers receive, and aligning grid planning to optimize investments are complementary strategies. These are outlined in RMI and AEU’s Large Load Tariff Principles, which are meant to help stakeholders balance competing interests, such as affordability, reliability, economic development, and emissions reduction.

By pairing tariff protections with these kinds of complementary strategies, utilities, regulators, and policymakers have an opportunity to transform large load growth into a driver of reliability and innovation rather than a source of high costs.