Hand turns a dice and changes the expression "bad cop" to "good cop", or vice versa.

Good COP, Bad COP? The Hopeful News in COP26…and Beyond

There is good news and bad news emerging from COP26. The bad news: The emissions reduction pledges made by nations so far are still likely to consign civilization to a 2.7°C warmer world by 2100 compared with pre-industrial times. The good news: Steady progress is being made in securing voluntary climate action commitments from non-state actors including businesses, investors, cities, and regions.

These commitments are the starting point to keep 1.5°C within reach. Standing alone, these institutions will only make a small dent in the ambition gap that stands between the current global emissions trajectory and where we need to be to achieve 1.5°C.

But these leaders don’t stand alone. Their commitments and actions prove what’s possible and inspire other public and private sector actors to step up. These increasingly common cycles of leadership and followership are becoming a major force for change in climate ambition and have the potential to significantly narrow the ambition gap. Positive feedbacks among diverse actors can help a policy, technology, business model, or other type of climate solution to spread rapidly across global systems. Understanding what makes these so-called ambition loops take off is key to unleashing the next stage of climate action.

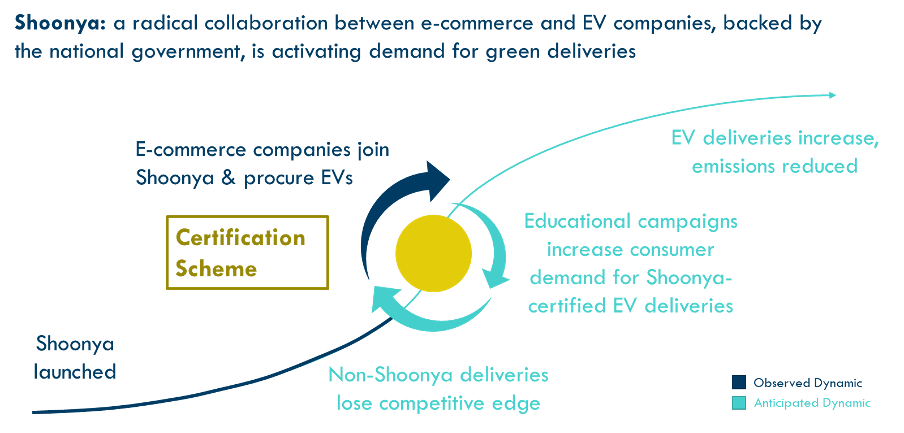

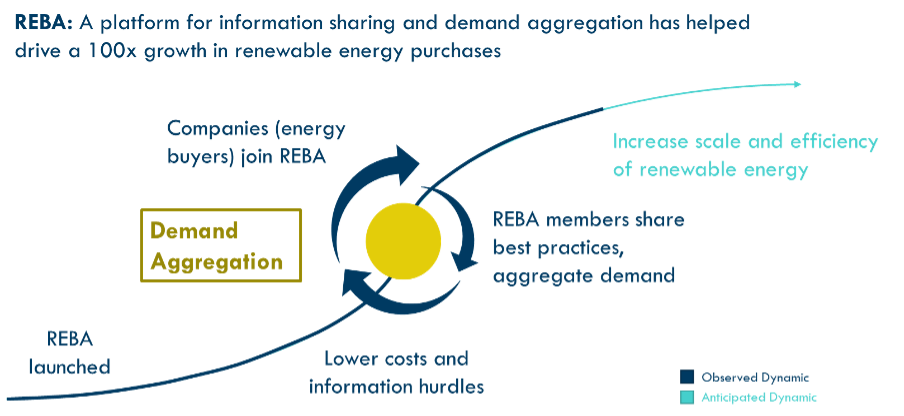

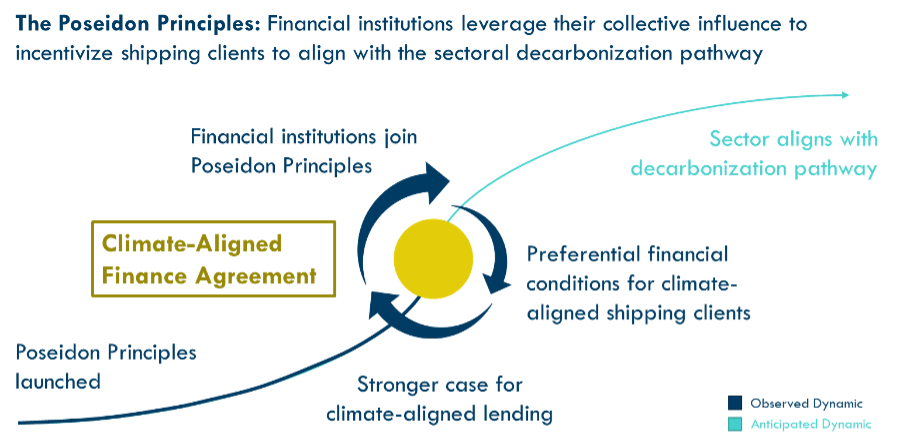

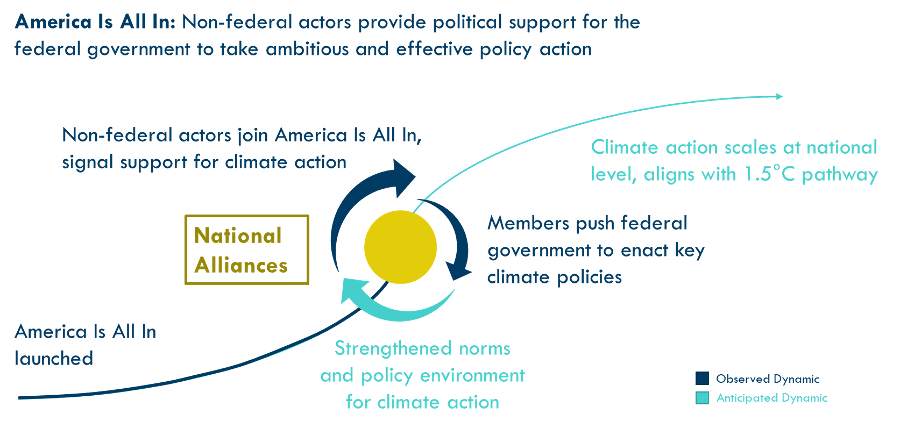

Key actors can create ambition loops in a wide range of market contexts by taking advantage of different types of feedbacks. Here, we offer examples of four different feedback mechanisms that helped create successful ambition loops:

- Certification schemes

- Demand aggregation

- Climate-aligned finance

- National alliances

These examples show how dynamic changes can be initiated from many different points in a system and how non-state actors can drive change.

1. Activating Customer Demand for Clean Energy Solutions through Collaboration and Product Certification

In India, a remarkable public-private coalition has launched a campaign to transform last-mile e-commerce deliveries and reduce urban air pollution by leveraging the power of customer engagement. Shoonya, based on the Sanskrit word for zero, aims to reduce cumulative CO2 emissions from the rapidly growing urban freight sector by 39 million tons by 2030.

Typically, goods ordered via e-commerce are delivered to customers in India’s cities via two- and three-wheeled vehicles. These deliveries have a high emissions footprint and contribute to poor urban air quality. Shoonya is helping transition these deliveries to electric in two ways. First, an educational campaign helps consumers understand the benefits of choosing electric delivery. Second, Shoonya will create a verification and branding system for electric delivery vehicles and the packages they deliver. This creates increased visibility, differentiation, and customer awareness for clean energy solutions while jumpstarting technical solutions and deployment. The hope is that consumers will opt for Shoonya-certified deliveries, pushing e-commerce companies to electrify their delivery fleets or risk losing customers.

Radical collaboration among a group of more than two dozen e-commerce companies, electric vehicle manufacturers, and charging companies created the foundation for this breakthrough program. Government leadership came in the form of public education, certification, and tracking. Coordinated action is helping transform a highly visible sector with the power to influence the overall pathway to vehicle electrification in one of the world’s fastest growing markets.

Certifications can increase visibility into supply chains for almost any good or service, helping consumers make informed choices about their purchases. Examples of supply-chain certification programs in other sectors include the Forest Stewardship Council certification of sustainable wood products, Better Cotton Initiative certification of sustainable cotton, and Marine Stewardship Council certification of sustainably harvested fish. The scope for enabling consumer choice of low-emissions products and services is vast.

2. Ramping Voluntary Procurement to Drive Economies of Scale

Between 2010 and 2020, US corporations voluntarily increased their purchases of electricity from renewable sources from 0.1 GW to over 10 GW. Corporate procurements reached 40 percent of all new carbon-free electricity capacity added in the United States in 2020. This is despite the fact that, for many corporate energy buyers, renewable energy purchasing can be an opaque and complicated endeavor. The Renewable Energy Buyers Alliance (REBA) helped to stimulate the cycle of leadership and followership among US corporate energy buyers.

REBA began by convening a group of large companies that were interested in increasing their purchases of renewable energy. These companies led the charge for policy changes that have liberalized markets and smoothed paths to renewables purchasing, while simultaneously sharing best practices for efficient procurement among themselves. This, in turn, drove increases in scale and efficiency in renewables projects that brought down costs and smoothed the pathway to more and faster transactions and higher shares of renewable power. In other words, REBA was able to mitigate the biggest risk factors around purchasing, making it easier for smaller buyers to join and contributing to its rapid growth.

The REBA model can be useful to jump-start economies of scale in other sectors facing similar challenges with price uncertainty and information barriers. The Sustainable Aviation Buyers Alliance, Renewable Thermal Collaborative, RE-Source, and India’s Energy Efficiency Services Limited are all examples of coalitions that operate on a similar theory of change. What could be the implications if manufacturers brought similar market scale to purchasing green steel or other primary materials?

3. Leveraging Climate-Aligned Finance to Decarbonize Capital-Intensive Sectors

Voluntary action by a group of lenders representing a third of global shipping finance has helped to speed decarbonization in this global “hard-to-abate” sector. The Poseidon Principles, the first example of a sector-specific climate-aligned finance agreement, shows us how the financial sector can leverage its influence to drive transformational change at the scale of an entire sector. Historically, financial institutions have found it difficult to move ahead of their peers on sustainability requirements for fear of losing market share. The Poseidon Principles overcomes this challenge through collective action. Launched in June 2019, over $1.2 billion in Poseidon-linked loans were provided in just the first year of the agreement.

Signatories of the Poseidon Principles steer their clients toward climate goals using a combination of financial carrots and sticks. For example, they might provide better loan rates to clients adopting cleaner technologies. As the case for climate-aligned lending grows stronger, more financial institutions are incentivized to join the Poseidon Principles. In turn, it becomes more difficult for shipping clients to find alternative sources of financing if they fail to meet climate goals.

The Poseidon Principles have also created spillover effects within the shipping industry, inspiring the launch of the Sea Cargo Charter, a similar framework for climate alignment among ship charterers, and the Shipping Criteria of the International Climate Bonds Standard.

Climate-aligned finance is a model that can be adapted to other high-emitting, capital-intensive industries: already, a similar initiative is underway for the steel sector, with aviation likely soon to follow.

4. Building National Alliances to Advance Climate Policy

With national governments increasingly preoccupied with COVID-19, economic challenges, security threats, and more, subnational actors are increasingly taking the lead on climate-related issues. The dynamics of non-state climate action are subject to ambition loops of their own, as networks of actors work together to pioneer and then replicate and scale new policies and solutions.

In the United States, federal leadership on climate action has been inconsistent through different administrations. With the re-entry of United States into the Paris Agreement, the next challenge for the federal government is meeting this commitment with concrete, credible policy action. Non-state actors such as local governments and private companies look to support from the federal government to turn their climate ambitions into action. In turn, these actions from non-state actors help push the federal government to pursue high-ambition climate policies.

America Is All In is a broad coalition of US-based non-state actors trying to move the needle on US climate action in two important ways. First, it is leveraging its expansive signatory base, representing two-thirds of the US economy, to advocate for ambitious, whole-of-society climate action at the federal level. Second, it is amplifying and supporting non-state actors pursuing voluntary climate action and showing the federal government where intervention would be most effective.

America Is All In importantly highlights both the extent of non-state actors’ influence and the sheer amount of support and action around climate change that already exists within the non-state actor community. Similar coalitions of non-state actors for climate action are beginning to emerge around the globe and can be found in Argentina, Australia, Japan, and beyond.

Initiating Exponential Change

As voluntary climate commitments become the new norm, it is more important than ever for non-state actors to ensure that their actions are as effective as possible in generating change beyond their own institutional “borders.” The ambition loops we have discussed in this post—certification schemes, demand aggregation, climate-aligned finance, and national alliances—show how exponential change can be initiated from nearly any part of society with the power of collective action.

To help non-state actors catalyze these ambition loops in their own networks, RMI is developing a series of retrospective case studies on successful past examples. For now, as we wait to see how ambitiously national governments will act at COP26, non-state actors should remember that they already have the power to get the ball rolling.