Aerial view of large storage tanks and loaded cargo ships at LNG port

Gas Gone Global: LNG 101

What is liquified natural gas and what is its impact on emissions, health, and economics?

As the name suggests, liquefied natural gas (LNG) involves turning gas into liquid form — a process known as liquefaction. Liquefaction does not alter the chemical makeup of gas, which is comprised of mostly methane plus varying amounts of different impurities, but it does make it denser. This enables ships and other carriers to move more gas over oceans between locations that lack direct pipeline connectivity.

What comprises the LNG supply chain?

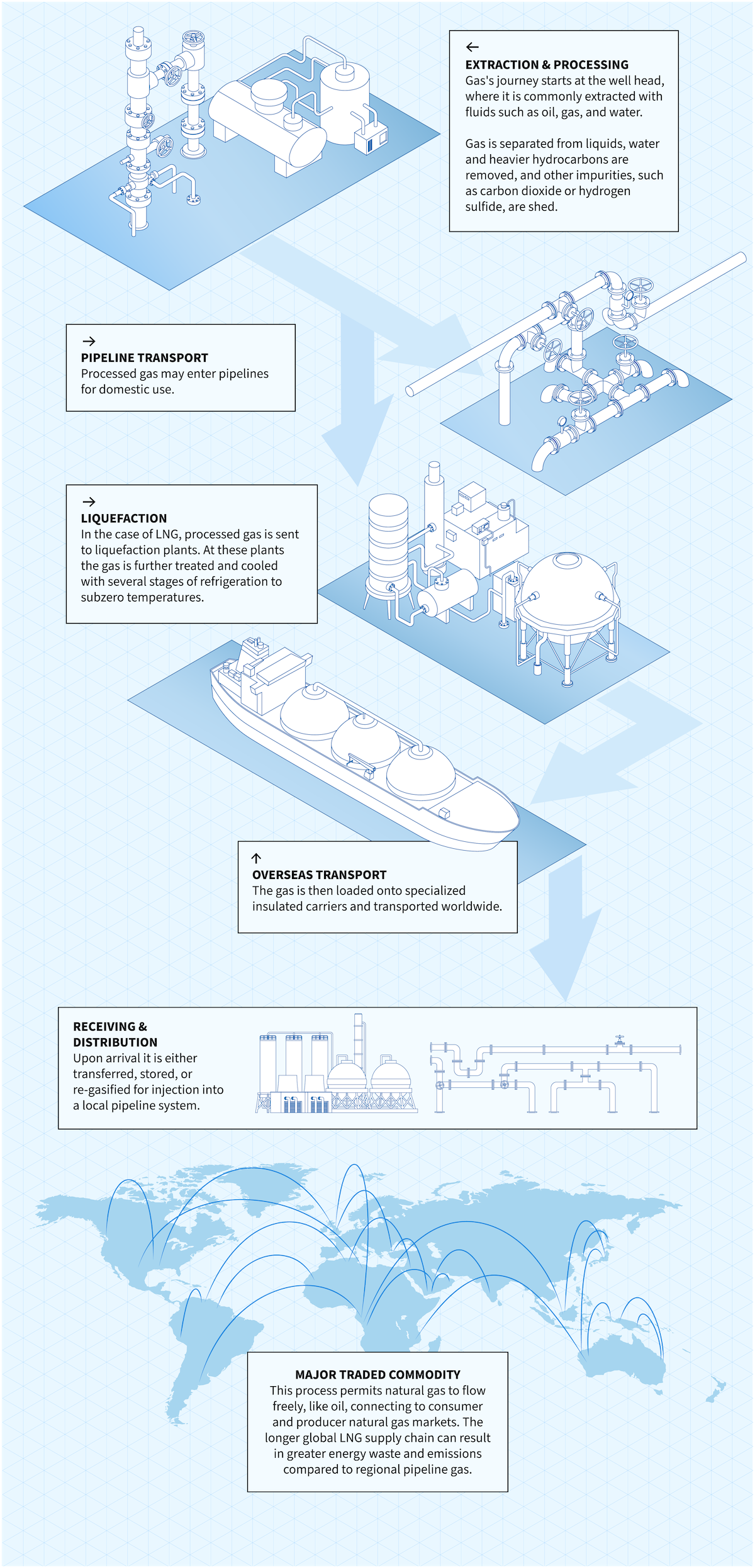

The LNG supply chain can be long. Starting at the oil and gas field — the initial point of resource extraction — some processing may take place once gas reaches the surface. Often, gas is then gathered from multiple fields and transported via pipeline for further processing before being placed in a transmission pipeline where it travels to an LNG terminal. Upon receipt, the gas is liquefied by cryogenically freezing it to compress it into a liquid.

Then it moves further. Specially designed super tankers or other vessels ship LNG long distances over the ocean. These vessels don’t always travel directly between origin and destination; they can reverse course or float for days or weeks before unloading. At the destination, LNG is re-gasified and stored so that it can finally be placed into a pipeline for transmission and distribution to industry and other consumers.

Where is the United States in the international LNG market?

While LNG shipping has been occurring in small volumes since the 1970s, it has ramped up significantly since 2015 amid a shale gas boom in the United States. Increased export capabilities of Australia and steady LNG trade from Qatar have also fueled market growth, as plotted below.

Source: US Energy Information Administration (EIA)

The current expansion underway of the US LNG market closely tracks the shale revolution unleashed by hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling. As recently as 2016, the US LNG exports were essentially nil. Today, the United States is the world’s number one LNG exporter, ahead of petrostates like Qatar and Russia.

New US LNG terminals are in planning, as charted below. If financed, built, and operationalized, this could roughly double US LNG export capacity in the next few years, adding to other countries’ anticipated capacity growth.

Source: EIA

How does LNG impact health, the environment, and safety?

Like any form of gas, when combusted, LNG emits carbon dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and other air pollutants. In other words, liquefying gas doesn’t minimize its health and safety impacts. When leaked anywhere in the supply chain, gas (both liquefied or compressed) can explode, cause fires, create smog, sicken people, and accelerate planetary warming.

Given its long and meandering supply chain, LNG is prone to leakage and loss. Research published in 2023 found that a methane leakage rate from the gas supply chain as low as 0.2 percent can be on par with the net greenhouse gas emissions from coal. Leaks can happen either unintentionally or on purpose anywhere in the LNG supply chain, from faulty equipment, loss during transport, and elsewhere, or intentionally by the practice of venting and flaring during routine and emergency operations.

Methane is a powerful heat-trapping gas, which has over 80 times the heating power of carbon dioxide in the near term. Methane also reacts to form smog — a local air hazard — and tropospheric ozone, another powerful climate-warming gas. Moreover, the production and burning of gas can release carcinogens and other air toxins like benzene and deadly gases like hydrogen sulfide. Preventing gas from leaking in the first place is a highly effective short-term mitigation strategy to immediately safeguard people and the planet.

The energy intensity of the gas liquefaction process itself is also important to highlight. Cooling gas to a liquid takes enormous amounts of energy, as does returning it from liquid to gas. Both processes are usually powered by fossil fuels. These processing systems are also capable of leaking gas and releasing methane with each of the many compressors, valves, and flanges — all potential leak points.

Does the distance LNG travels have an impact?

Since LNG typically travels much longer distances than pipeline gas — and is fed through much more extensive processing, transport, and storage equipment — it risks resulting in greater emissions impacts. The further LNG travels, the more the gas can escape — elevating its methane emissions intensity.

In 2023, the top four importers of US LNG were the Netherlands, France, Japan, and South Korea. These voyages over thousands of miles leave room for days of leakages, and that’s before LNG finally arrives at a port. Data provided by OceanMind reveals the wide variation in distances traveled by LNG cargo. For example, LNG imports to Japan on average travel 5,200 miles. The longest recorded journey for a Japan-bound cargo stretched to 52,000 miles — 10 times further — demonstrating how some cargoes waste significant energy along the way.

A recent study in the journal Communications Earth & Environment found a strong correlation between LNG emissions intensity and the number of miles traveled. In the study, an estimated ~0.1 ton of CO2 equivalent per ton of LNG cargo is boiled off as gas cools and escapes in transit when shipped from the United States to Europe, while double that rate (0.2 tons of CO2 equivalent per ton of LNG cargo) is released on the much longer journey to Asia.

This boil off in transit requires gas to be utilized for power, re-liquified, flared, or sent into the air. Gas that is lost during LNG’s trek is not only harmful to people and the planet, it is also sheer waste, on par with exporting cars only to throw a few overboard every time you want to sell overseas. Each mile traveled is more wasteful and emits more into the atmosphere.

How might LNG affect US energy prices at home?

When gas demand is rising and captures a higher price abroad than at home, this can affect US market prices for residential and industrial gas use and gas-powered electricity. One US Department of Energy study (p. 34) found that a tripling of US LNG exports in 2050 could lead to a 25 to 30 percent increase in Henry Hub natural gas prices. Such a rise in gas prices could strain US households. But it could also drive a further cost advantage for renewable electricity generation and battery storage, considering current trends.

What can be done to prevent leaks and waste?

Fortunately, strategic interventions to reduce methane in the oil and gas supply chain can be simple and cost-effective, especially in upstream production. Instituting routine monitoring, rapidly responding to remote leak detection, prohibiting venting and routine flaring, bolstering maintenance, attending to equipment fixes, and financing upgrades can significantly slash methane in production.

Mitigation potential is also at the ready in gas transport and storage. Some of the same fixes mentioned above — prohibiting venting, routine monitoring, and attending to leaks — apply to the LNG supply chain.

Estimates of LNG supply chain reduction potential can be analyzed using RMI’s Oil Climate Index plus Gas (OCI+), which quantifies and compares emissions intensities from global oil and gas assets, as illustrated in the figure below. With OCI+, market actors can better understand the impact of oil and gas supply chains across disparate resources and geographies.

If LNG markets expand and gas supply chains lengthen, energy waste and emissions are expected to rise. Much more will need to be done to lessen the negative impacts.

Enhancing transparency can better account for emissions and facilitate stocktaking. Publicly verifying measurements with satellites and other instruments can spur action to stop methane releases and prevent wasted gas. Formally and openly certifying methane leakage rates is a market-forward means of keeping gas out of the air, which can also boost profits by earning premium pricing for low-emissions natural gas and avoiding regulatory fines. And adopting regulations that prevent the trade of high methane intensity gas can be a powerful market incentive.

Technology, transparency, policy, and market action are all critical levers to prevent greater energy waste and methane emissions, especially if LNG continues to expand the reach of gas globally.