Decarbonizing Tall Buildings with a New York State of Mind

A decade ago, a deep retrofit of the Empire State Building reduced energy demand in the iconic skyscraper by more than a third. The now-archetypal project, which involved manufacturing 6,514 super-windows on-site, avoided costly upgrades to the central cooling system and achieved a shocking three-year simple payback. Now the building’s owners and their partners are back for the sequel, part of a superhero squad decarbonizing skyward in Gotham City.

New York Governor Kathy Hochul just announced the awarding of $20 million to four pioneers redefining asset management in the age of decarbonization as part of the $50 million Empire Building Challenge, administered by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA). Winning projects included commercial offices by Empire State Realty Trust and Hudson Square Partnership and affordable multifamily housing by L+M Fund Management & Invesco Ltd. and Omni New York. It is a milestone moment after more than a year of collaboration in the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) Empire Building Challenge.

The Empire Building Challenge (EBC) convened a cohort of 10 major New York real estate partners and their top-tier engineering consultants to solve one of the toughest challenges in the transition off fossil fuels—decarbonizing tall buildings in cold climates. In New York specifically, about 70 percent of carbon emissions come from buildings. The EBC partners together represent 127 million square feet of New York State building stock, providing a massive opportunity to slash emissions directly and blaze a trail for others.

A Tall Order

New York’s Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (Climate Act) mandates 100 percent zero-emissions electricity by 2040 and economy-wide carbon neutrality by 2050. That means that billions of square feet of New York buildings have 28 years to wean off the fossil fuel combustion and fossil-fueled steam that heat the majority of the building stock today. For many buildings, that translates to roughly one asset replacement cycle, and buildings that simply replace today’s fossil fuel equipment with newer versions of the same will not be in compliance with Climate Act mandates before the equipment reaches the end of its lifetime. Already electric heat pumps can reduce emissions in New York buildings, and the climate benefits of clean heating equipment installed today will only grow as the grid decarbonizes, as shown in the graph below.

Tall buildings present unique challenges, however. Even if building owners wanted to simply rip out boilers or disconnect district steam pipes and replace them with the same capacity of air-source heat pumps, it is often not physically or economically feasible to do so. As anyone who has searched for a New York City apartment knows, space is a severely limited resource, and the same goes for spare roof space for additional heating equipment. And even if a building has ample roof space, the heating distribution systems inside the building—whether for steam, air, or high-temperature hot water—may need to be converted to something compatible with the output temperatures from today’s heat pumps. A simple swap to low-efficiency electric resistance heating, meanwhile, would be a step backward in terms of energy affordability and at scale would increase grid loads substantially.

Given the challenges of decarbonizing tall buildings in densely packed cities, traditional approaches—such as building performance audits that aim to tweak but not transform—will likely be insufficient. The solution must involve more than a reactionary mindset or a swap-out of a single component or system. Fortunately, we can do better.

Presenting a Solution

The solution is Resource Efficient Electrification (REE), an approach emerging from over a year of collaboration between EBC real estate partners, their industry-leading consultants, and a NYSERDA team that includes RMI. REE applies to the wide array of building types, vintages, and systems in New York. Crucially, it incorporates the dimension of time, both in the arc of a project—a deep retrofit over time in the age of decarbonization—and in system design, returning to 10XE first principles like “meet minimized peak demand; optimize over integrated demand” and “optimize over time and space.”

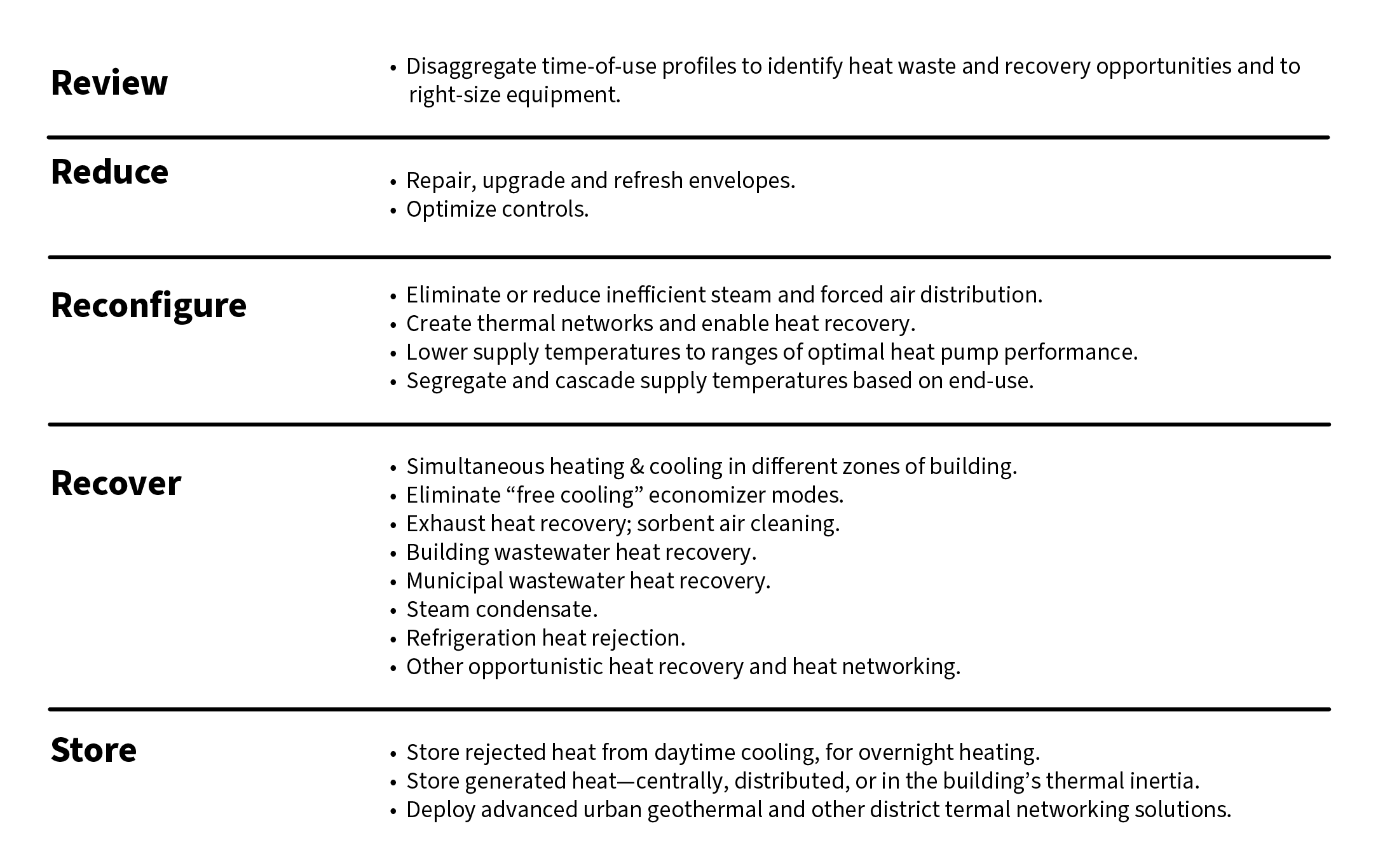

REE focuses on enabling steps that can be grouped into helpful categories:

With these enabling steps asset managers can replace fossil heat generation with rightsized heat pumps that can economically meet a majority of loads today. The toughest conditions in tall buildings may warrant separate consideration, solving for decarbonization of outlier conditions and resilience, or testing real-world operation that gives confidence to remove the last fossil sources.

Moving Heat

Often electrification discussions start with heat pumps, for understandable reasons. They are an important part of the solution. But it’s important to remember that heat pumps are a general category of equipment that move heat from one place to another. For tall, large, and complex buildings, a variety of heat pumps can serve different purposes. As described in a recent Canary Media article, “some move heat into the building—from the air, the ground, or other potential sources like wastewater or district systems. Other heat pumps can be used as part of the building’s distribution system, bumping up supply temperatures and moving or recovering heat from where it is not wanted to where and when it is.”

The benefits of load reductions are fairly well known in integrative design practice. Other integrative benefits of these steps are underappreciated but can unlock Resource Efficient Electrification. In many load-dense commercial buildings, substantial cooling occurs year-round. Today the default solution is to run economizer cycles, with so-called “free cooling” that releases unwanted heat to the outdoors (as pictured in the image accompanying this blog post of waste heat exhaust in winter). But if that heat is recovered and redistributed to where it is wanted, or stored for evenings or mornings warm-ups, commercial buildings can drastically reduce heating loads, downsize equipment, and even heat themselves for much of the year. Multifamily buildings, on the other hand, can tap and recover waste heat resources in exhaust air and wastewater, which are intrinsically well-matched loads to ventilation and domestic hot water. Thermal storage in fluids, ice, phase-change materials and the building’s thermal mass allow load-flatting and equipment modulation, minimizing the needed size of centralized equipment as well as flattening peaks in the building’s energy demand.

Thermal networks within and between buildings can redefine how we think about heat, mining and moving Btus in an urban thermal playground of sources, nodes, and sinks. Urban-scale thermal infrastructure, whether grown organically or master-planned, can extend decarbonization opportunities to space- and resource-constrained heat partners. Cities like Seattle and Denver have recently taken important steps to harvest existing thermal resources, tapping valuable heat flowing beneath the streets in municipal wastewater.

Making the Leap

So, what does this all mean for a building asset manager today? For starters, the steps toward REE don’t have to occur concurrently or even sequentially. Sequencing may be dictated by other factors like tenant turnover, investment cycles, repositioning, violations of building performance standards, facade maintenance or other safety considerations, or proactive strategic pilot programming. But the action item for portfolio managers everywhere, with urgency, is to map out an asset investment decision tree of decarbonization pathways to avoid. This the way to prevent reactionary scrambles and regressive investments. With planning and strategic execution, in 28 years we can find our building stock at its decarbonized destination.

Inaction is not an option. Even putting aside the global climate imperative, the building performance standard of New York’s Local Law 97 makes the status quo illegal for much of the building stock. And the rise of corporate carbon neutrality commitments changes “do nothing” into “risk everything” for commercial real estate, which hinges on keeping anchor tenants happy. In the housing sector, outdated and inadequate energy systems have severe repercussions for affordability, quality of life, and health and safety, an issue laid bare by the recent deadly fire in the Bronx.

Fortunately, building owners are not alone on this journey. EBC cohort winners have charted the course, and with this recently awarded funding, they will make exemplary leaps forward. They now embark on implementation that no doubt will reveal insights and opportunities relevant to a global, multidisciplinary audience. Scaling requires a solution ecosystem, which is now under construction, building on a foundation of case studies and industry education. Technologies to enable decarbonization are arriving in New York, some imported from Nordic countries that lead the United States in thermal networking, and some emerging from homegrown channels like the Clean Fight or Third Derivative.

Soon, NYSERDA will launch the Empire Technology Prize, a $9.5 million accelerator program to advance emerging technologies and business solutions that will transform tall building decarbonization in New York and around the world. Additionally, NYSERDA and the Building Energy Exchange just launched the Empire Building Challenge educational series High Rise / Low Carbon, promoting the market for low carbon retrofits of tall buildings across New York State. You can find more information about future events here.

Perhaps most exciting, the REE approach fundamentally shifts the dialogue around heating decarbonization. For building managers, designers, infrastructure planners, utility regulators, and policymakers, REE expands toolkits across the dimensions of time and space to find new solutions to a hard problem. We can decarbonize tall buildings by 2050, if we start now.