Funding Our Future: Creating a One-Stop Shop for Whole-Home Retrofits

This article is part of RMI’s “Funding Our Future: Investing for Climate Impact” series, in which we discuss how we are informing the federal government about how federal infrastructure funds should be spent to help tackle climate change.

Decarbonizing the US building stock must start by ensuring that low-income residents have easy access to affordable, healthy, safe, and climate-aligned housing. With over $5 billion in new weatherization and energy efficiency funding passed in the bipartisan 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), now is the time to begin restructuring energy programs to deliver comprehensive retrofits to as many low-income households as possible. On March 30, the US Department of Energy released the Weatherization Assistance Program’s IIJA funding availability notice, providing a momentous opportunity for communities across the United States to deliver whole-home retrofits for low-income housing.

Across the United States, 26 million low-income households are currently dependent on fossil fuels for heating and powering their homes — a problem for the climate and public health. Many of these households are unable to afford necessary home upgrades or access retrofit programs as renters. Lack of investment in affordable housing contributes to increased health and safety risks, unaffordable utility bills, and climate pollution.

A comprehensive whole-home retrofit approach to move homes off fossil fuels — delivered through a “one-stop shop” implementation model — can maximize benefits to residents and more efficiently use available funding to prioritize low-income households.

Whole-Home Retrofits for Affordability, Resilience, and Health

To support affordable, safe, and healthy homes, retrofit programs must provide a full range of home retrofit services. RMI and its partners have identified four categories of retrofit services that encompass a whole-home retrofit and align with common funding parameters:

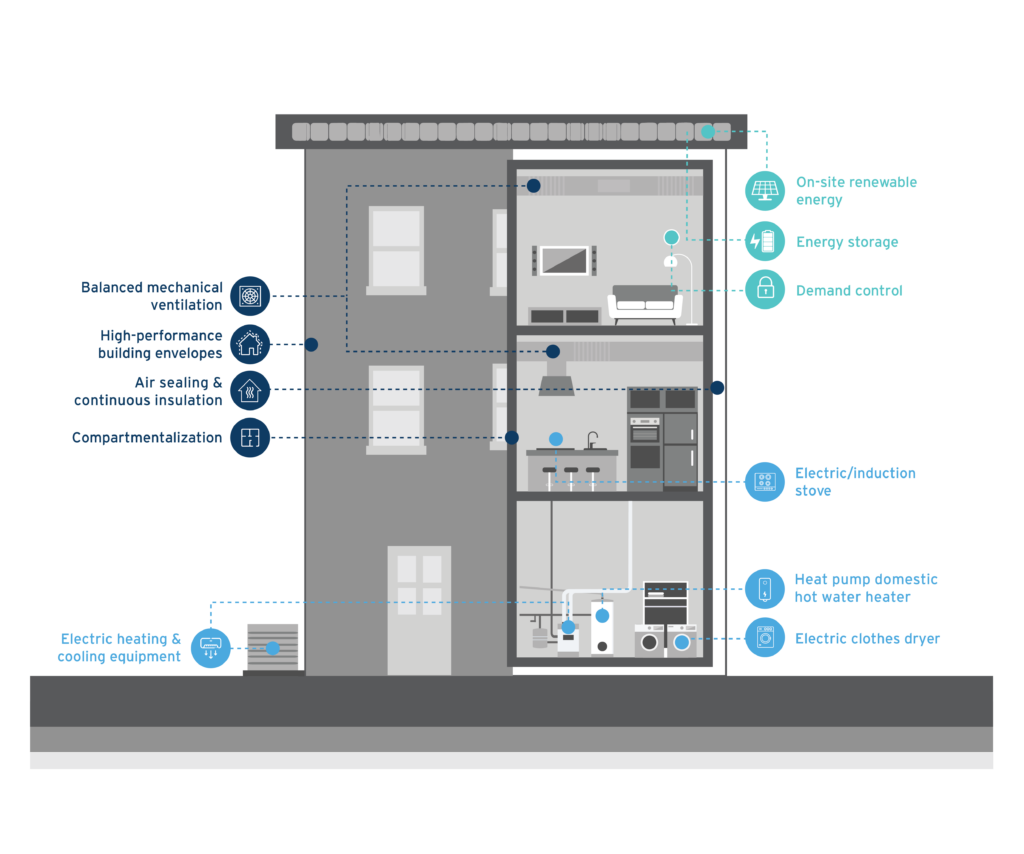

- Health and safety services include toxic chemical removal, roof repair, wiring repair, and indoor ventilation improvements. These are the common interventions required for habitable, safe households.

- Weatherization and energy efficiency services include building envelope upgrades such as improved insulation, better windows, and tighter air sealing to reduce energy use.

- Appliance electrification replaces fossil fuel appliances, like gas stoves and furnaces, with efficient electric alternatives, like induction stoves and air source heat pumps. Electrification eliminates indoor air pollution and on-site climate emissions and reduces overall energy use.

- Energy assistance is necessary to ensure households have access to affordable, renewable electricity. Energy assistance can include limits on energy burdens (the portion of household income that goes to energy expenses), utility bill assistance, rooftop solar programs, and access to community solar.

RMI’s research shows that a whole-building approach directly improves resident and community well-being. Whole-home retrofits reduce harmful exposure to air pollution and mitigate climate impacts, which disproportionately harm disadvantaged communities where homes have historically been poorly ventilated and located closer to power plants and other major polluters. Whole-home retrofits can also deliver more resilient homes, ensuring residents are protected from extreme weather events. Finally, whole-home retrofits future-proof households against rising, volatile gas prices.

The Need for a “One-Stop Shop”

The current retrofit programs available to low- and middle-income communities don’t provide comprehensive retrofit services, lack sufficient funding, and pose barriers to access. For example, homes with issues like faulty wiring and lead paint can’t access retrofit programs because many programs bar customer participation until health and safety concerns are addressed — but they don’t provide funding to do so.

That is why federal, state, and local agencies must coordinate to consolidate funding and program services so homeowners and building owners have a single point of entry to access low-cost, whole-home retrofits. This program model has been administered at the state and local level, for instance in California’s Low-Income Weatherization Program and Philadelphia’s Built to Last program. A “one-stop shop” retrofit program for deep energy retrofits is akin to walking into a car dealership and picking your make and model, features and aesthetic specifications, and financing and maintenance plan all at once. Applied to whole-home retrofits, this model allows residents and building owners to determine their retrofit needs, access contractors, and receive support from multiple funding sources.

New Federal Funding Can Be the Catalyst

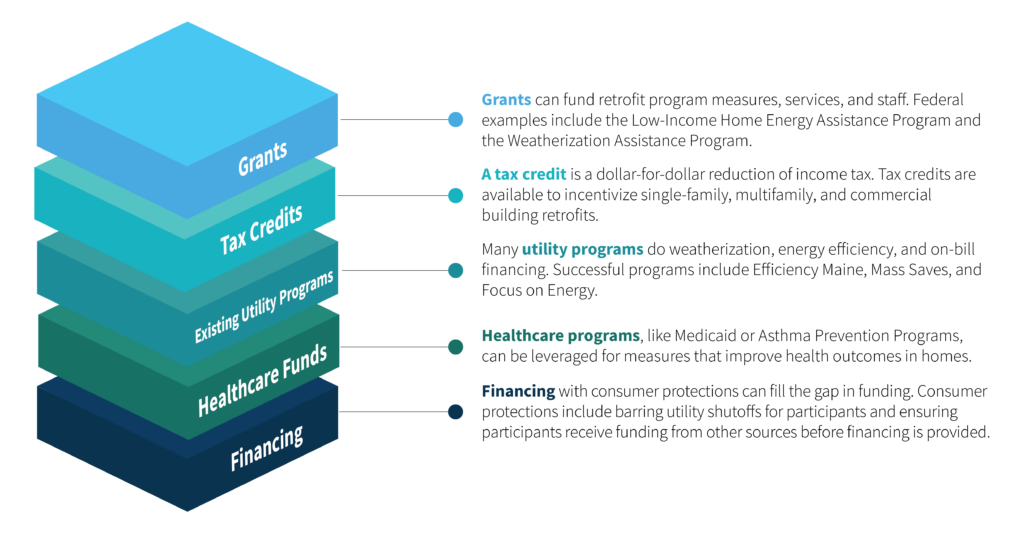

A one-stop shop program requires funding for the four services of a whole-home retrofit alongside money for the administrator, program management staff, technical advisors, and contractors. The more than $5 billion for weatherization and energy efficiency from the IIJA must be paired with other federal funds, such as the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program and existing utility programs, to provide whole-home retrofits. IIJA expanded key grants such as the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Block Grant Program, Weatherization Assistance Program, State Energy Program, and INSULATE — all of which can be stacked in a retrofit program. Other possible funding sources include state and federal grants, tax credits, existing utility programs, healthcare funds, and consumer-protected financing.

Programs will need to leverage multiple streams of funding from various sources to ensure all measures for a whole-home retrofit are available at low or no cost to eligible participants. For example, Philadelphia’s Built to Last program stacks over 15 sources, including utility money and healthcare funds, to support a comprehensive retrofit program. Scaling these programs from one-off programs to programs available in every community across the country will require national information sharing, restructuring of funding sources, and a commitment to accessible whole-home retrofits.

The bipartisan infrastructure funds provide a multibillion-dollar opportunity to revitalize our housing sector. If we put the money to strategic use — centering community input and needs — the federal funds will help us secure healthier home environments for millions of households.