How Virtual Power Plants Can Help the United States Win the AI Race

Unlocking the capacity of virtual power plants can help big tech power data centers, fast.

Introduction

This moment offers a generational opportunity to invest in America’s electricity future. Power demand is projected to grow faster than it has in decades, driven in large part by data centers and other large new loads. Meanwhile, much of the nation’s existing grid infrastructure is aging and will need to be replaced. Because many traditional solutions now face high costs and supply chain constraints, finding new ways to quickly, cost-effectively upgrade the electricity system will be essential to power the next stage of American economic growth.

Fortunately, proven solutions are ready to be deployed. RMI research shows that nearly all of the next decade’s forecast grid needs could be met by fast, affordable, flexible solutions such as energy efficiency, virtual power plants (VPPs), advanced transmission technologies, and new generation sited at existing points of interconnection through solutions like clean repowering and power couples.

VPPs — grid-integrated, dispatchable aggregations of distributed energy resources such as batteries, electric vehicles, smart thermostats, and other connected devices — alone could scale to meet over 20% of US peak demand in 2030 and even reach a market size on par with projected data center growth. This brief outlines why VPPs are particularly well-suited to meet the needs of emerging large loads and explores how novel commercial structures could accelerate their deployment.

Grid Operators Aren’t Ready for Surging Large Loads

Utilities and grid operators must ensure sufficient generation and delivery capacity before allowing large loads to interconnect. Yet bottlenecks across planning, permitting, procurement, and construction are slowing progress:

- Utility-scale generation is delayed. Gas turbines are backlogged through at least 2028, while geothermal and advanced nuclear remain years to decades away. Meanwhile, over two terawatts of wind, solar, and storage projects sit in interconnection queues, and the total timeline to interconnection now averages more than five years.

- Delivery infrastructure is constrained. Transformer wait times have doubled to as much as five years. Even modest distribution system upgrades take years, and large transmission projects can take decades.

The result is that new data centers and other large loads are being forced to wait while utilities and grid operators prepare their power systems for increased demand. Case studies illustrate the severity of these constraints:

- In Northern Virginia, the world’s largest data center market, Dominion Energy has warned that new connections could face wait times of up to seven years.

- In Ohio, AEP paused new data center service agreements in 2023 due to grid constraints.

- In the Dallas-Fort Worth area, equipment procurement and grid connection challenges are delaying some data center delivery dates until 2027 or later.

To speed interconnection, new solutions will be necessary. One of the most promising is expanded deployment of VPPs.

Why VPPs Are a Great Match for Large Loads

Three characteristics make VPPs uniquely well-suited to support rapidly growing large loads:

1.VPPs are fast and flexible

VPPs are unique in their flexibility and speed to deployment. Unlike conventional resources, VPPs can be sited at all levels of the power system, which means they can help manage a range of constraints that may be slowing data center interconnection. For example, National Grid’s Connected Solutions VPP utilizes multiple distributed energy resources to both alleviate local network constraints and provide bulk system services by participating in wholesale markets. Green Mountain Power utilizes customer batteries to reduce its resource adequacy obligations and has proposed a major expansion of the program to increase customer resilience in the face of local outages.

VPPs can also be deployed much quicker than traditional upgrades, and serve as enduring grid resources or as a bridge to long-term conventional infrastructure investments. California’s Demand-Side Grid Support Program has enrolled over 750 megawatts (MW) of customer-sited storage — a 500 MW increase from January to October 2025. In Ontario, a 90 MW residential VPP enrolled 100,000 homes in just six months. Arizona Public Service’s Cool Rewards thermostat program has added up to 40 MW of capacity each year.

2. Procuring VPPs alongside large loads mitigates planning risks

VPPs are highly modular: they can be procured in almost any size, with contracts adjusted up or down on short notice. This modularity makes VPPs especially effective for mitigating the risks associated with uncertain demand forecasts.

Expanding generation and grid capacity takes years, while large loads are requesting interconnection now. The mismatch between the time it takes to build supply and the urgency of demand creates risks: underbuilding our power systems could lead to lost economic development opportunities or reliability risks, while overbuilding burdens customers with unnecessary costs. These risks are compounded by the uncertainty of large load forecasts and the siloed nature of generation, transmission, and distribution planning. Rather than making large, lumpy investments based on uncertain forecasts, modular investments like VPPs can mitigate risks by adding flexible capacity that can be scaled to match real-world needs.

3. VPPs offer some of the lowest-cost capacity available today

VPPs often provide the lowest cost capacity for incremental demand. For example, Brattle’s Real Reliability report found that 400 MW of VPP resource adequacy costs just $2 million annually — compared with $43 million for equivalent new gas plants and grid upgrades. RMI’s Power Shift shows VPPs could cut system generation costs 20% by 2035 by offering a cost-effective complement to new gas, large-scale battery storage, and network improvements.

VPPs can serve demand so cost-effectively because they allow utilities to more efficiently use existing, underutilized grid infrastructure. Exhibit 1 illustrates this point. In this example, 14 gigawatts of 24×7 demand (equivalent to 20% of current ERCOT system peak), could be met with only about 300 hours per year of VPP-enabled demand flexibility, alongside increased utilization of the existing system.

Exhibit 1

VPPs can either complement or provide the same function as on-site flexibility — shifting loads of the data center itself. Research and commercial activity have started to demonstrate that it’s technically feasible and valuable to build data centers with on-site flexibility in mind. However, it may still benefit data center owners to complement on-site flexibility with VPPs, especially in cases with technical challenges or high opportunity costs associated with curtailing or flexing data center demand.

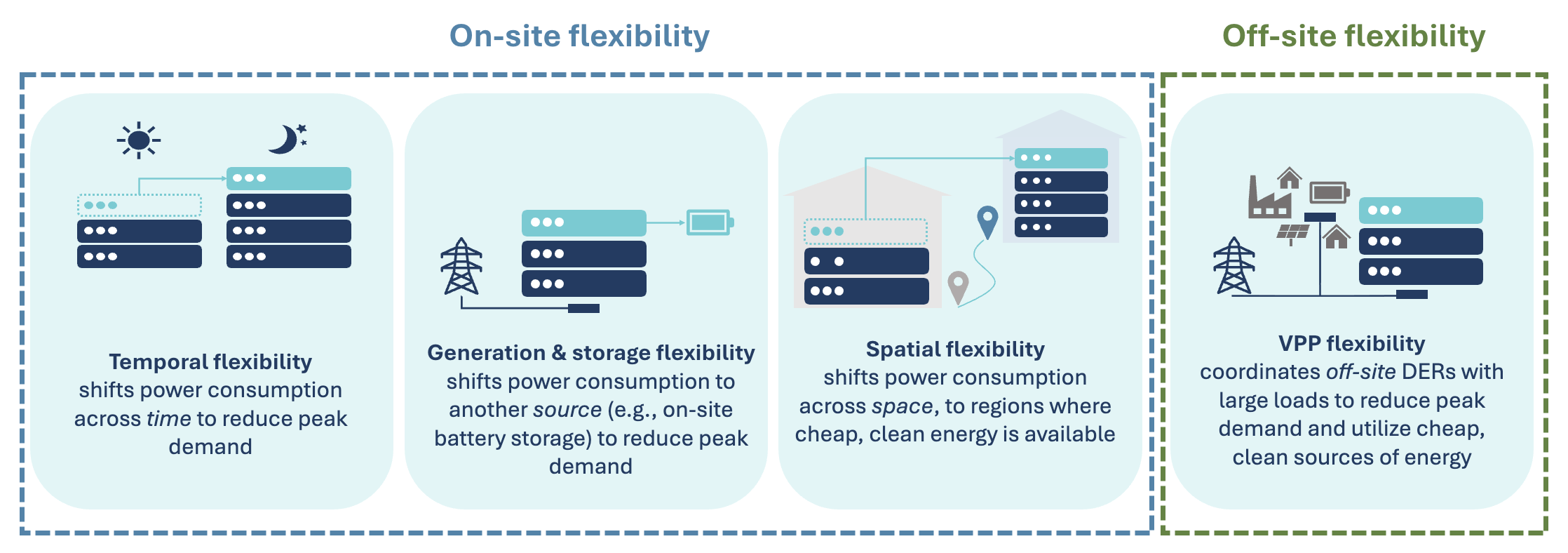

Exhibit 2 shows the range of on- and off-site flexibility solutions available to large loads such as data centers.

Exhibit 2: Options for data center flexiblity

New Commercial Models to Accelerate VPP Deployment and Large Load Interconnection

Scaling VPPs to support large loads will require new commercial and regulatory structures. Today, there are no clear, scalable ways for data center companies to invest in VPPs, for utilities to validate that VPPs can provide the grid services needed to enable interconnection, or for any parties to leverage VPPs to provide expedited interconnection of new loads.

The three illustrative commercial models below offer a non-exhaustive set of options for large loads, VPP aggregators, and utilities or market operators to contract with one another to ensure quick, cost-effective grid capacity. Each model shifts different risks and responsibilities across large loads, VPP companies, and utilities/market operators. But each one includes three fundamental transactions:

- Large load customers “sponsor” and provide capital to invest in VPPs at scale.

- Utilities or market operators set an “exchange rate” so that aggregators or large loads can offer expanded VPP capacity and receive expedited interconnection.

- VPP aggregators (with varying degrees of utility involvement) develop and deliver needed capacity to utilities or market operators.

Model 1: Pass-Through Funding for Utility-Managed VPP

This model is similar to a sleeved power purchase agreement (PPA) commonly used in green tariffs, but applied to VPPs. In a sleeved PPA, the utility procures an asset on behalf of a customer and agrees to be the offtaker of that asset’s energy. Renewable energy credits (RECs) and energy at a specified price are passed through (or “sleeved” through) the utility back to the customer.

Pass-through funding for utility-operated VPPs implies the following arrangements between parties, broken out into two different options:

Option 1A: Direct investment in a specific VPP project

This version looks like the sleeved PPA agreement described above, with procurement of a specific VPP project by the utility, sleeved through to the large load customer:

- Large load-utility/market operator contract: the utility and large load enter a contract in which the large load pays to purchase a VPP that will be owned or contracted and operated by the utility. In exchange, the large load is granted an expedited interconnection timeline from the utility.

- VPP–utility contract: the VPP guarantees capacity across a certain number of needed hours per year. The utility is responsible for purchasing the required capacity from VPPs that it deems necessary to justify expedited interconnection. The VPP (not the large load) is liable for delivering in accordance with this contract. This is similar to how many VPP aggregator contracts are structured with utilities today.

This model shares features with the Clean Transition Tariff proposed by Google and approved in Nevada, which allows corporate offtakers to support emerging clean-firm technologies at cost. When applied to data centers and VPPs, the model would function similarly, but the sleeve could include an additional attribute: speed to power.

Option 1B: Indirect investment in utility demand-side management programs

This version is a broader arrangement between the utility and large load customer — not enabling investment in a specific asset but rather allowing for the expansion of customer VPP programs through contributing to the utility program budget.

- Utility–large load contract: The utility and large load enter into a contract where the large load pays to increase the utilities’ demand-side management program budget in exchange for an expedited interconnection timeline. It is at the utility’s discretion to expand or invest in any additional demand-side management programs needed to justify expedited interconnection.

Key design considerations:

- The utility faces financial risk if the large load customer departs or fails to enter service. This risk can be mitigated by structuring contracts with the large load to assure full cost recovery of the VPP (e.g., by requiring sufficient up-front payments or long-term contracts).

Model 2: VPP Capacity Transfer

In this model, large loads directly fund the development of a third-party VPP. The VPP developer is responsible for securing offtake, with the utility or market operator acting as a clearing house for certifying new capacity and granting interconnection rights. One recently announced concept for a large-load funded, third-party VPP is Voltus’s Bring Your Own Capacity product.

This model is most likely feasible in a region where VPPs can participate in wholesale markets, where there are existing processes for accrediting and transacting capacity. It may also be possible in a vertically integrated geography, with a utility agreement to expand or procure a VPP program — but lining up that agreement could present a chicken and egg problem in that an offtake agreement would be desired for a large load to invest, but a utility may require proof of ability to deliver prior to signing an offtake agreement.

Contractual agreements like liquidated damages and hedges may help derisk the offtake agreement for large loads. Measurement and verification standards, along with aggregator qualification programs, may help assure utilities that the VPP is able to deliver.

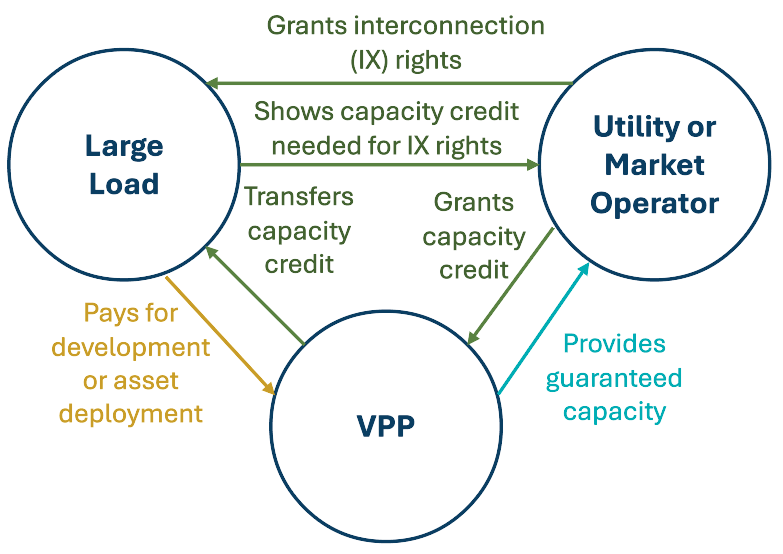

The following arrangements could be in place across parties:

- Large load–VPP contract: The large load directly contracts to procure a VPP from an aggregator or to invest in DER assets that can be aggregated into a VPP in a specific market. The aggregator is responsible for developing the VPP in a way that mitigates system-level constraints on large load interconnection. Note that the VPP aggregator could also be a retailer in this model.

- VPP–utility/market operator contract: The VPP enters into an offtake agreement with the utility or participates in the wholesale market, independent of the large load. In a wholesale market, instead of entering into a contract, the VPP could register and clear the capacity market. In this transaction, the VPP would need to receive proof of the services it is providing in the form of something like a transferable “capacity credit.”

- Large load–utility contract: The large load and the utility or market operator enter into an agreement by which capacity credits can be exchanged for expedited interconnection.

Key design considerations:

- This model requires a transferable capacity credit that can be transferred from the VPP to the large load customer in exchange for expedited interconnection with a transparent exchange rate. Generating such a credit may be more feasible in a wholesale market that already has approaches for capacity accreditation. Otherwise, accreditation mechanisms would need to be established.

- The large load needs to be relatively certain that the VPP will be able to contract with the utility or clear the market. Transparent standards for performance and certification may help increase confidence in the VPP’s ability to deliver. It may be difficult to align the timeline for capacity accreditation with the timeline for large load construction.

Model 3: VPP as Reliability Reinforcement

In this model, the large load invests in a VPP as its first line of defense to provide flexibility as required by a utility or grid operator. The load further hedges against delivery risk by installing on-site backup generation and/or on-site demand flexibility capabilities. The following contracts exist between parties:

- VPP–large load contract: The large load invests in the development of a VPP, which is designed to specifically reduce load during the times required to enable a flexible interconnection agreement or interruptible tariff contract. The VPP aggregator dispatches based on information from both the utility and the large load, so that it can control and verify that it is providing flexibility for the large load in accordance with its utility/market contract.

- Large load-utility/market operator contract: The large load and utility/market operator enter into a flexible interconnection agreement or interruptible tariff wherein the data center agrees to be flexible — with off-site flexibility included as an option in a broader package with clear rules for measurement and verification — in exchange for an expedited interconnection timeline. The large load is largely responsible for reducing load during times as specified in the contract and may also contract with on-site backup generators or use on-site demand flexibility as a backup to meet the requirement.

Key design considerations:

- This model requires a strong measurement and verification approach for ensuring off-site flexibility is providing assured reductions on peak in accordance with the large load–utility contract.

Exhibit 3 summarizes the differences between the three commercial models.

Exhibit 3

Creating the Conditions for Takeoff

For large load-powered VPPs to scale, stakeholders across the electricity ecosystem must create an enabling environment. Three areas of engagement are especially important: interconnection policy, integrated planning and data access, and customer protection.

Interconnection policy

Both generator and load interconnection policies are slowing data center deployment. Most regions still allocate scarce generator interconnection capacity on a first-come, first-served basis. When generator interconnection capacity is constrained, this type of approach can delay the connection of the projects offering the greatest system benefits, whether affordability, reliability, speed-to-power, or decarbonization. Meanwhile, even when generation and transmission infrastructure is available, the tools and processes utilities have for assessing load interconnection are insufficient to quickly interconnect large loads.

Several states and regional transmission organizations are updating their policies to expedite load and/or generator interconnection when large loads and generation are bundled together:

- Oregon is exploring a large load tariff that could let data centers choose between conventional planning or an expedited option in which they directly fund all required generation and interconnection infrastructure.

- Nevada approved a “Clean Transition Tariff” enabling Google to buy geothermal power at a premium, creating a scalable model for bilateral procurements. This type of tariff opens a window for large loads to pursue their own policy goals, at cost — including decarbonization or possibly speed-to-power.

- The California Independent System Operator (CAISO) uses an auction system in which load-serving entities bid points to prioritize generators in the interconnection queue. This may allow large loads to expedite bundled generators.

- The Southwest Power Pool (SPP) has proposed new tariffs for bundled large load and generation. Its High-Impact Large Load Generation Interconnection Assessment (HILLGA) would allow loads and generation to apply jointly for an expedited 90-day study. A potential future filing could establish Conditional-High Impact Large Load Service (CHILLS), enabling large loads to connect before necessary transmission upgrades are completed if they agree to curtail power during reliability events.

Accelerated interconnection will be critical for large loads to fully leverage VPPs’ speed and flexibility. State regulators and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission both have central roles to play in advancing reforms that reduce wait times for new generation and load. One priority is making sure that interconnection tariffs and processes clearly and explicitly recognize eligible VPPs and clarify what constitutes a qualified VPP program.

Integrated planning and data access

VPPs can provide value across the grid — from meeting peak demand to relieving local network constraints — but capturing that value requires coordinated planning and more transparent planning outputs. Integrated planning can ensure, for example, that the capacity delivered by VPPs is additional to existing reliability services such as resource adequacy, supporting data center interconnection while maintaining equivalent levels of reliability for customers.

In market regions, distribution owners, transmission owners, and wholesale market operators will need to coordinate to identify the relevant constraints and solutions necessary to integrate large loads. For example, market operators may identify the hours in which generation capacity is necessary to ensure resource adequacy, while transmission and distribution utilities identify requirements for safe interconnection.

In vertically integrated territories, a single utility manages generation, transmission, and distribution planning, which in theory should make coordination easier. In practice, siloed processes and mismatched timelines often prevent effective co-optimization. Stronger integration across planning functions would allow VPPs to maximize value to the grid and reduce interconnection delays for large loads.

Utilities and market operators can also improve data transparency and access, enabling VPPs to deliver the values identified in planning. One priority is making sure that planning outputs such as capacity accreditation are available to VPP developers. Furthermore, planning for and settling load across systems operated by multiple organizations will require enhanced electronic data sharing. In order to facilitate VPP enrollment of customers at the speed and locational specificity required to serve large loads, regulators can require utilities to implement secure data-sharing standards like Green Button Connect.

Customer protection

Regulators can ensure that introducing large loads does not place undue financial burden on the rest of the utility’s customers when implementing solutions that leverage VPPs. Key approaches include:

- Designing large load payments via transparent tariffs that fully recover VPP costs (including program administration and customer incentives), plus a reasonable profit for the VPP aggregator.

- Requiring up-front payments and long-term contracts in tariffs to increase liquidity of VPP companies and mitigate the risk of stranded assets in the case that large loads exit service.

- Evaluating retail rate design to ensure that large loads and the VPPs they sponsor do not shift costs to other customers.

Several states are already structuring large load tariffs with customer protection in mind, including developing structures that allow large loads to reduce risk for other customers by bringing their own generation such as VPPs. In Kansas, for example, a recent settlement includes an optional rider where the utility can credit customers for bringing their own generation to serve their load at market-accredited capacity that the utility would otherwise have to procure. These approaches aim to reduce risks of cost shifts and rate increases from stranded costs.

Conclusion

Data centers and other large loads cannot wait years for traditional generation and infrastructure upgrades. Virtual power plants offer a faster, cheaper, and more flexible alternative. The commercial models proposed in this paper can unlock large load-driven VPPs at scale by more efficiently allocating risk among utilities, VPP developers, and large customers — aligning incentives and unlocking new pathways for rapid deployment. In turn, this could benefit us all — strengthening reliability, lowering costs, and powering the next wave of US economic growth.

Acknowledgment: The authors thank the following individuals for their contribution to the thinking that inspired this work: Ben Pickard, CPower; Josh Keeling, UtilityAPI; Ron Nelson, Current Energy Group. The authors thank the following individuals for their review: Kelly Crandall, UtilityAPI; Dana Guernsey, Voltus; Emily Orvis, Voltus; Natalie Mims Frick.