The Key to Market Transformation

How a simple framework can help spur decarbonization

You’ve Heard It Before

Remember how Blockbuster gave way to Netflix, and taxis fell behind Uber? Each revolutionized an industry by offering a better value — or better outcomes — to the customer. These were not just disruptions — they were full-scale market transformations.

The term “market transformation” is used frequently, though rarely with a clear definition. What exactly is it? What can we do to bring it about? And what factors could induce market transformation in building decarbonization so that, for example, renovations of aging, unhealthy buildings universally include better efficiency and electrification?

This article leverages existing research to define, as well as offer a framework for, market transformation.

But What Is It, Really?

“Market transformation” refers to a marked shift from incumbent offerings to products and services that deliver better outcomes to consumers. W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne call this “step change in value for buyers” the critical determinant of success for new markets. Better outcomes for consumers, or comparable outcomes at an appreciably lower price, stem from the development of new capabilities in the supply chain.

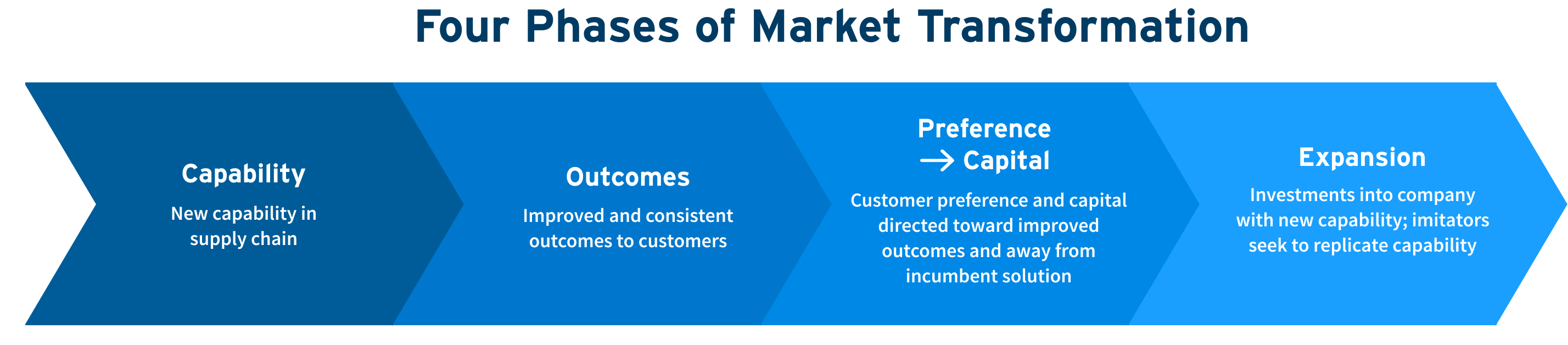

The supply chain delivering the new (improved) product or service starts receiving more resources because of the shift in customer preference toward these better outcomes. At the same time, the “new entrants” delivering the better outcome make it difficult for companies behind the incumbent product to hold market share and raise capital to maintain operations — which further hastens the change in the market. Finally, imitators seek to replicate the new capability so they, too, can deliver the improved outcomes, effectively making the improved outcomes “the new normal” — i.e., transforming the market (Exhibit 1).

Those looking to leverage this understanding of market transformation to develop a plan can start by:

1) pinpointing the capabilities in the supply chain necessary to deliver outcomes capable of driving preference away from the incumbent solutions, such as roof imaging technology that identifies optimal rooftops for solar panel installation, thus helping drive the widespread adoption of solar energy;

2) finding ways to invite and support the development of those capabilities, like funding research, exploring intellectual-property-sharing and/or industry partnerships, seeking well-matched investment, or offering consumers incentives to try new technologies;

3) identifying external events that would change how customers perceive and value outcomes of existing and new capabilities, like raising awareness of the co-benefits of electrification and energy efficiency (such as air quality or improved insurability) is doing for decarbonization.

Such efforts can trigger the sequence of events behind market transformation.

The Market Transformation Sequence in Motion

By showing the direct relationships among capabilities, outcomes, customer preference, capital, and expansion, the four phases depicted in Exhibit 1 make it easier to see what types of activities contribute to market transformation (for a deeper dive into the topics of value delivery, how markets function, how to find what outcomes customers look for, and how companies seek advantage over one another, see the works of Michael Porter, Hamilton Helmer, Clayton Christensen, Anthony Ulwick, Renée Mauborgne, and W. Chan Kim). This simple framework allows for a common understanding among key players in an industry and can focus them on those levers most able to drive change. It can help those committed to, say, building decarbonization recognize how to think about building a supply chain able to deliver appropriate solutions that building owners and other end users prefer over the business-as-usual alternative.

Of course, while the development of new capabilities often sets off the causal sequence shown in Exhibit 1, external conditions can also play an important role in accelerating or hindering market transformation. Changes in commodity prices, the regulatory environment, information availability, and societal expectations can influence customer preference for the outcomes delivered by an existing capability. For example, a sharp rise in propane costs may change how customers value all-electric cooking and heating appliances.

Numerous examples of this chain of events occurring exist across industries. The new capability of the smartphone replaced not only legacy cell phones and landlines, but also cameras, music devices like Walkmans, and more — even unlocking outcomes that consumers did not anticipate nor initially think to ask for. The paired capabilities of automatic car dispatch and payments via a mobile phone app delivered preferred outcomes to customers that shifted their preference from taxis to the platforms of Uber and Lyft. In buildings, low-emissivity window coating is now near-ubiquitous, due in part to cost reductions, high quality, scalability, and rising consumer demand. In each of these cases, and in many others, a new capability in the supply chain delivered improved outcomes to a segment of customers, starting a chain of events that irrevocably changed — i.e., transformed — the market.

Seeking Market Transformation

A range of historical examples show us what is possible. New capabilities that deliver improved outcomes can upend the old way of doing things and drive extraordinary change. The term “market transformation” must not be used as a repository of hope or a vague claim, but as a guide toward specific, meaningful, sustained shifts in the market and the availability of improved solutions that building owners and end users prefer.