Powering a Brighter Future for Nigeria

Interconnected solar minigrids are powering homes and businesses with reliable, affordable, clean energy in Africa’s largest country.

Alheji Gembo runs a small shop with cold drinks out of his home in Zawaciki, a housing settlement in Northern Nigeria. In the past, the unreliable power from the national grid made his business challenging. Now, Gembo, along with the 1,000 other homeowners and businesses in Zawaciki, gets his power from an interconnected solar minigrid. “Before we had this minigrid, we suffered in our work given the quality of the light,” he says.

Most Nigerians refer to electricity as “light,” and Gembo says on average he had about four hours of light each day. “Sometimes we even spent two days without light. But now that we have this minigrid... they give us at least 16 to 20 hours of light a day, every day.” With more reliable power, Gembo has grown his small business from one fridge to four, serving cold drinks to this hot arid community.

Zawaciki — sited on the verge of northern Nigeria’s sunny savannah region — is one of soon to be five interconnected solar minigrids in Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country with over 200 million people. An interconnected minigrid supplies an underserved rural, semi-urban, or even urban community that is already connected to the conventional electricity grid but that has unreliable power. Interconnected minigrids consist of a renewable energy source such as solar panels, and sometimes battery energy storage and a backup generator. They are connected to the main electrical grid and can buy energy from the main grid when needed, especially at night to reduce the cost of battery backup.

Like much of sub-Saharan Africa, this oil and gas-rich country struggles to provide its growing population with sufficient electricity. Electricity demand far outstrips the supply, meaning constant power outages. Yet, located just north of the equator, Nigeria’s potential to generate solar power rivals or exceeds the best conditions in Europe and the United States.

So RMI, along with the Global Energy Alliance for People and Planet (GEAPP) as well as Nigerian partners, have implemented five pilot interconnected minigrids, three of which are operational and two of which are still in development.

Ibrahim Sali runs a distribution company in Zawaciki, delivering about 10,000 liters of bottled water throughout the housing settlement each day. Prior to the minigrid, Sali had to run his diesel generators to power his facilities daily. “Before now we were not having light very well, but with this [minigrid] now there is light and it is helping our business,” he explains. “We make more profit now because with the light, I don’t use diesel like before.”

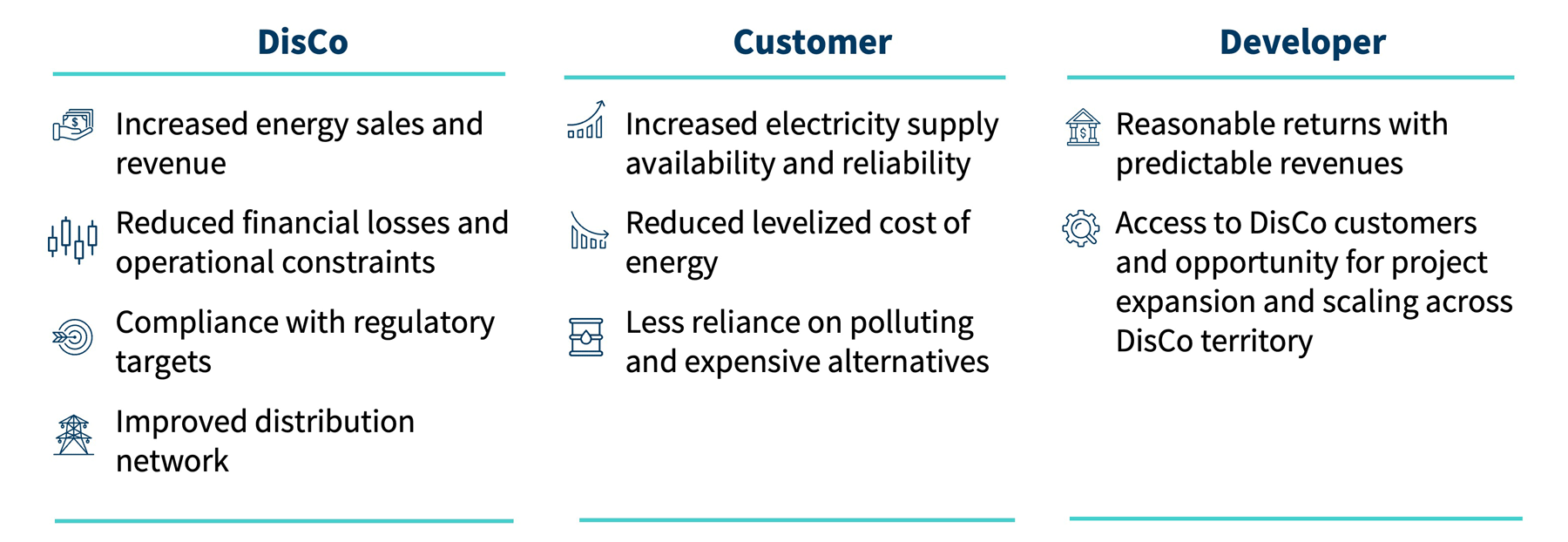

A win-win-win solution

The Zawaciki interconnected minigrid is the first in Northern Nigeria and the second in the country. It is currently the largest minigrid, with 1 megawatt (MW) of solar power and diesel generator backup provided by solar developer Bagaja Renewables. Plans are advancing to add 1 megawatt-hour (MWh) of battery storage to the minigrid in the next few months. The project is connected to the utility, Kano Electricity Distribution Co. (KEDCO) and KEDCO and Bagaja both supply the community with electricity at different times of the day, depending on the available resources.

“We are towards the end of the national grid, so whenever there is a lull in generation or frequency issues it definitely affects us the most,” says Hussaini M. Sadiq, KEDCO’s chief strategy and performance officer. “Because of that we are seriously challenged in terms of energy availability, and in some areas we have reliability issues and voltage issues.” The minigrid helps solve those problems by providing another source of electricity from the abundant sunshine in Nigeria. This also reduces reliance on electricity from the national grid, 75 percent of which comes from gas-fired generation plants.

By April 2025, KEDCO’s goal is to have at least 10 percent of its energy come from embedded generation and 50 percent of that to be from renewables. The Zawaciki minigrid is a pilot project for KEDCO to demonstrate the effectiveness of an interconnected minigrid, and so far it has been a huge success.

KEDCO is one of the 11 electricity distribution companies (DisCos) in Nigeria. DisCos not only struggle with providing sufficient power to their customers, they also lose a lot of revenue due to both technical losses and a low collection ratefrom end-users. In 2023, KEDCO only collected 62 percent of what it billed its customers. But with the minigrid, the customers have prepaid meters, and the money goes directly to Bagaja. Then KEDCO bills Bagaja for the electricity it supplied for the month as well as the service charges for the use of its existing distribution network, bringing both Bagaja and KEDCO’s collection rates to 100 percent.

The Zawaciki minigrid even powers two large commercial customers, China Civil Engineering Construction Corp. (CCECC) and Dala Dry Port. The technician who runs the diesel generators at CCECC says he went from purchasing 400 liters of diesel to power the generators a day to only 150–200 liters every couple of days. The company, which builds major railways throughout Nigeria, is saving a lot of money by running generators much less often.

“There’s a compelling opportunity for these kinds of models because it provides a win-win-win for utilities, developers, and customers,” says Fauzia Okediji, manager of utility innovation at GEAPP. “There’s a strong, attractive investment opportunity for developers. DisCos are able to provide better supply to their customers, improve reliability, and improve their revenues. And the customers are able to enjoy a better supply of power and displace diesel generators.”

Across Nigera, and much of Africa, people use diesel and gas generators to supplement the unreliable power from the grid, leading to an estimated 33 million tons of climate pollution emissions each year. This is also extremely costly, especially after the removal of the fuel subsidy in 2023, which nearly tripled gas prices. Wide-spread use of generators is also costly for utilities because, as people produce their own electricity, utilities lose revenue. This loss makes utilities unable to cover operational costs and prevents them from funding the upgrade of the distribution infrastructure. It’s a vicious cycle, as the poor distribution infrastructure is partly to blame for the unreliable power.

However, when an interconnected minigrid is built, the solar developer can also improve the distribution infrastructure that they will use for the solar power, meaning the utility’s grid power can run across upgraded infrastructure. The developer will pay off that investment through the customer payments for the electricity. Another win for everyone involved.

A bustling market gets light

These minigrids aren’t just for rural areas at the end of the transmission lines. About 260 miles south of Kano, in the middle of Nigeria, lies Abuja, the capital city. Its nearly 4 million people suffer from poor electricity service as well. And nowhere is this more evident than at Wuse Market, the largest market in Abuja with 2,000 stalls. When the power goes out, thousands of shop owners fire up diesel generators, choking the air with noxious emissions and a deafening clamor.

But soon a 1 MW solar minigrid with battery storage will power the entire market, providing reliable and silent power to the stall owners who before received only 6–8 hours of power each day. The minigrid is run by GVE, a solar developer, in a three-way agreement with Abuja Electric Company and the Wuse Market Association. Mary Alaele Baelanki, a fashion designer who makes women’s and men’s clothing, runs her sewing machines and iron in her stall at the market. “It’s good working with the GVE solar panel because even though rain is falling the light is OK. And there is no need to buy [fuel] for our generator,” she explains.

Ali M. Paul is also a tailor at the market, and explains that before the minigrid there was a lot of challenges due to the lack of power. “At times we had a couple of days or a couple of hours without light. And that affected our business. The customers that patronize us could hear and see the noise and air pollution from the generators. When GVE came in we were happy because they have come with another alternative.” Paul describes how before the minigrid, to power his six industrial sewing machines, he might have to buy 10 liters of petrol for his generator each day, which cost him 5,000 or 6,000 naira (US$3.50–US$4.00). But now he pays just 3,000 naira for electricity every two weeks.

Baelanki and Paul were both part of the 40 kilowatt (kW) pilot project implemented in 2019 that covered 24 stalls. In the next two weeks GVE will commission the full minigrid project powering all 2,000 plus stalls with 1 MW of solar, 1.2 MWh of battery storage, and 1 a MVA diesel generator. John Baiyekusi, who runs one of the ten cold storage stalls at the market, was not part of the initial pilot. He runs his generator about 8 hours every day to preserve the fish, chicken, and seafood stored in his four freezers and a large cold room. And with high diesel prices he says, “It's not easy but there was no other option, surely the solar will benefit us. It will give us an advantage and opportunity.”

“The market received about 6 to 8 hours supply on the average per day, and we saw the need to augment the energy supply in the market,” says Chris Nwachukwu, head of field operations at GVE. After piloting the smaller system for four years, he says they learned a lot of lessons to be able to deploy the full project. “Going forward, the interconnected minigrid technology is the perfect solution for underserved areas and commercial hubs like this market and this is something that we intend to scale,” Nwachukwu explains. Currently GVE is planning interconnected minigrids in three other markets in Abuja.

Other Nigerian interconnected minigrids

In addition to those detailed here, more interconnected minigrids are currently providing power or coming online across Nigeria soon:

- A 352 kW interconnected minigrid is providing electricity to more than 2,000 households and 141 commercial users in Toto, a rural community in Nasarawa state.

- Soon a 500 kW interconnected minigrid will power 1,400 homes in the semi-urban community of Robiyan.

- A 185 kW isolated minigrid in Mokoloki will soon be connected to the national grid making it the country’s fifth interconnected minigrid.

A brighter future

“We need to be innovative and creative around how we look at energy access and take a more regional approach to addressing the more than half a billion people that don’t have access to electricity,” says RMI’s Africa Program Director Suleiman Babumanu. “Minigrids have a huge potential to close down the energy access gap, not only in Nigeria but across the world.”

RMI’s Africa Program Director Suleiman Babumanu

RMI’s Africa Program Director Suleiman Babumanu

“Minigrids have a huge potential to close down the energy access gap, not only in Nigeria but across the world.”

- Suleiman Babamanu, RMI Africa Program Director

These minigrid pilot projects have proved that interconnected solar minigrids improve people’s lives, increase revenues for the utility, and provide solar developers opportunities to scale and expand projects.

KEDCO’s Sadiq explains that “Kano is a strategic state in terms of commercial activities, there are a lot of industries and we have over 3,000 industrial customers. For most of these customers, availability, reliability, and steady voltage is a major challenge. So we see this as an opportunity for us to solve these issues.” With the success of the Zawaciki minigrid, the largest minigrid in the country, KEDCO is looking at how to scale up, and plans to have hundreds of minigrids in the near future. “The official outlook is very good,” he says. “The future is bright.”

Top image: A technician cleaning the solar panels at the Zawaciki minigrid.