It’s Time to Put Urban Form on the Climate Agenda

How we build — and rebuild — our cities will make or break our ability to meet global climate targets.

This article summarizes a presentation made by Gehl and RMI at New York Climate Week in October 2024. The full presentation is available here. A shortened version of this article was originally published on World Economic Forum.

Globally, urban sprawl is likely to be directly or indirectly responsible for 30 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions. That might seem like an astonishingly big number, but sprawl means more roads and parking spaces, more cars, bigger cars, more infrastructure, bigger houses, and more land. And when you add up the emissions related to car dependency, the embodied carbon of materials, energy use, food waste, and the loss of carbon sinks, the figure starts to make sense.

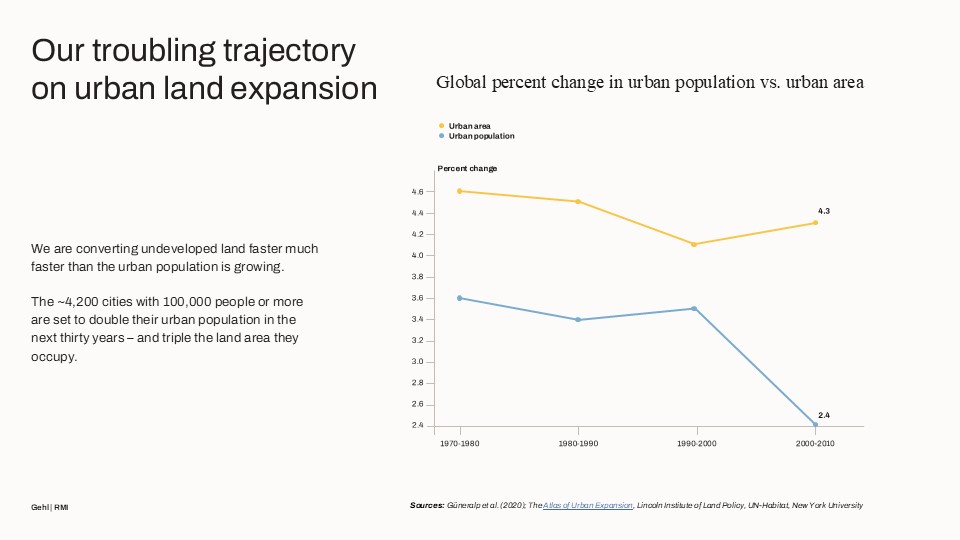

There is a lot of city-building to come; the global urban population is swelling by the equivalent of a New York City every 45 days. And it is not trending well; urban land consumption is increasing 67 percent faster than urban population growth.

Despite what’s at stake, urban land use, urban form, and urban design are largely missing from the global climate discourse. These topics were not, for example, featured among the 93 sessions hosted by the COP29 Presidency (while “space leaders” and “football clubs” got their own events).

This is not just an urban planning problem. It is also a challenge of imagination. Across the globe, the popular perception is that to increase opportunity for urbanizing populations we need an urban planning paradigm that favors car travel, separates land uses, and provides more built space per person. In fact, the opposite is true: compact, walkable cities are better at promoting well-being and opportunity and produce far less emissions. These climate-friendly cities are not places of scarcity; they are places of abundance.

By designing our cities with people’s needs and the climate in mind, we ensure that population growth does not derail our climate targets. Per capita emissions in compact, mixed-use, multi-modal cities are typically two to three times lower than the average emissions in the countries in which those cities are located. There are also vast differences in the emissions profiles of countries with similar levels of development (U.S. per capita emissions are more than double those of most European countries, for example). There are several factors driving these differences, but the most significant and consistent one is the divergence in urban form; low emissions countries generally have more compact, mixed, multi-modal cities and neighborhoods.

This kind of development is what we call “climate-aligned urbanism.” It enhances the way we move, consume, and live, and reduces our impact on the planet in five main ways:

Car Dependency

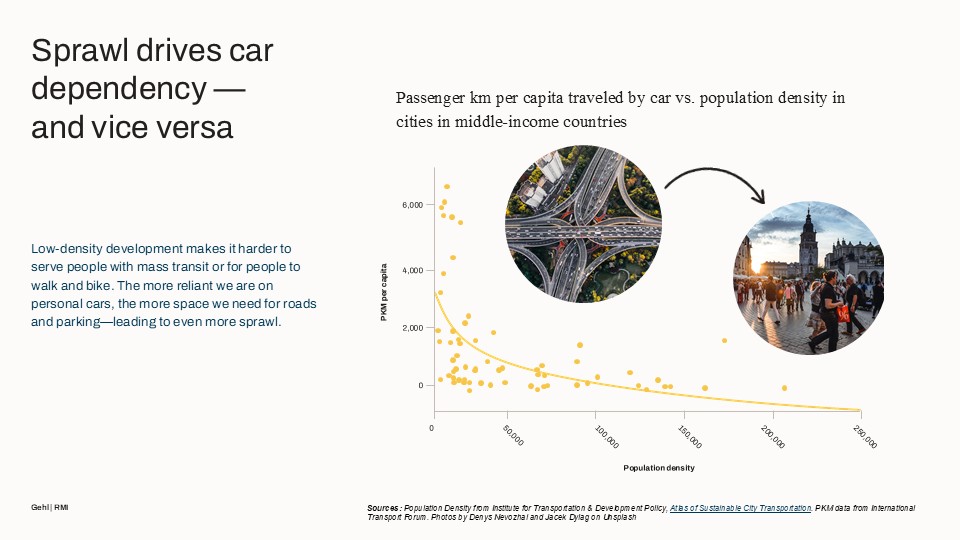

Low-density development makes it harder to serve people with mass transit or for people to walk and bike. The more reliant we are on personal cars, the more space we need for roads and parking — leading to even more sprawl. In climate-aligned urbanism, everyday amenities and services are closer to where people live and are better integrated with the transportation system. This allows people to move around more efficiently and in more social and active ways.

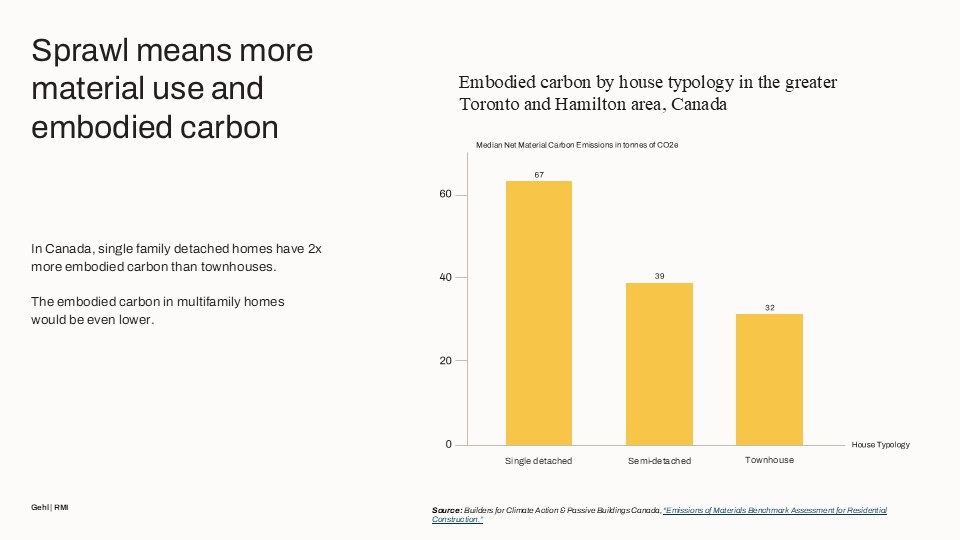

Embodied Carbon

When we build single-family houses in suburbia, we use more materials and thus more embodied carbon. There is 40 percent less embodied carbon in the average mid-rise multifamily housing unit than there is in a single-family one, and a lot less embodied carbon in the associated infrastructure, such as roads and sewer lines. For example, London, Istanbul, and Buenos Aires all have similar metropolitan populations but London has three to four times more road material stock on account of sprawl.

Energy Use

Even though energy efficiency has increased, we are building bigger houses, negating the efficiency benefits. The average home in the United States is at least 50–75 percent larger than in Europe. And a single-family detached home in the United States uses almost three times more energy than apartments in buildings with five or more units. And with sprawl, more energy is required to actually transmit and distribute the required electricity and water to those homes.

Forest Loss

Globally, 60 percent of urban expansion between 1970 and 2010 was on agricultural land. And the land near cities tends to be the richest and most productive farmland, with a long history of cultivation. When we exchange that land for sprawl, agriculture gets displaced to other, less productive land. Meaning we need more land, more water, more fertilizer, more run-off, to produce the same amount of food. These direct and indirect effects threaten 5-8 percent of remaining forestland through 2050.

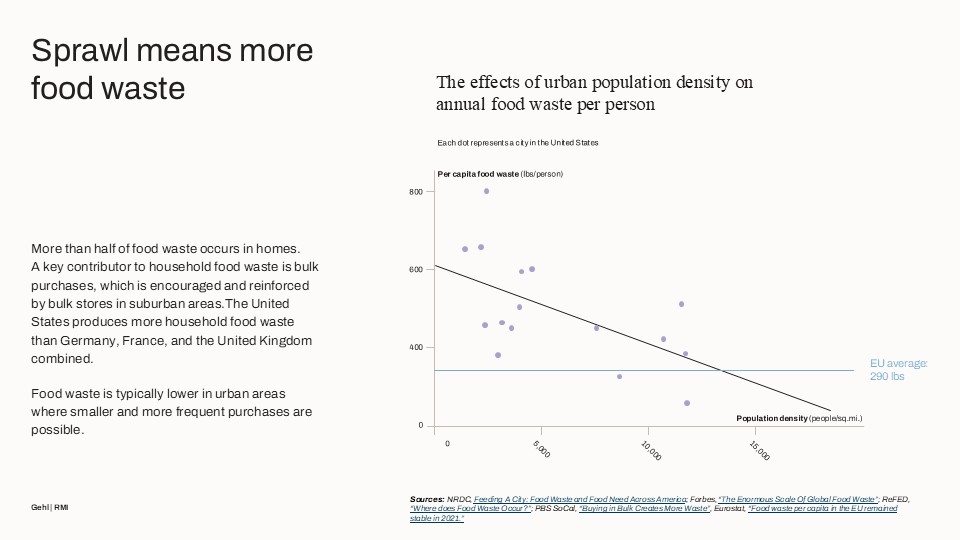

Food Waste

In richer countries, more than half of all food waste occurs in homes. A key driver of food waste is large, infrequent purchases (humans are bad at math and evolutionarily predisposed to hoarding). This type of purchasing happens when you have to drive to a bulk stores in suburbia versus pick up what you need for dinner from your local grocer. The higher the population density of a city, the less food waste per person.

So, what are the solutions?

Wherever possible, we need to prioritize retrofitting the cities we’ve already built, preserving both their embodied carbon and the concentration of human energy and human capital in existing urban fabric. “Greenfield” development should be rare, but excellent.

Promoting infill development, removing restrictions on multifamily housing and lifting parking requirements, developing cycling and pedestrian infrastructure, and building more homes and commercial clusters close to high-quality transit are all things any city can do to move toward climate-aligned urbanism. In the United States, addressing America’s chronic housing shortage intelligently — by building more housing where most people need it — can deliver similar climate impacts as the country’s most aspirational transportation decarbonization policy.

The guiding principle that makes climate-aligned urbanism work is attention to the human scale, and it is already happening around the world:

- Shanghai’s 50 km of new routes have connected 4.8 million residents to the new public spaces along the Huangpu River within 15 minutes’ bike ride.

- Sydney redesigned George Street, once the most congested in the city, as a people-centered public space that also moves 8,000 transit riders per hour.

- Buenos Aires introduced 27 upgraded public spaces into its largest informal settlement to create a walkable neighborhood and introduced infill housing.

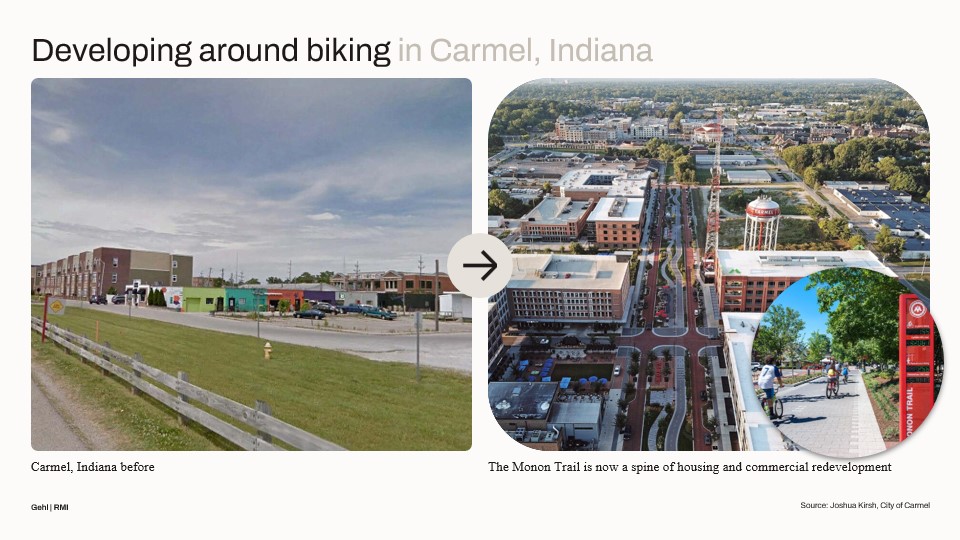

- Indianapolis invested $27 million in biking infrastructure downtown, catalyzing $170 million in private housing and commercial redevelopment; now 70 percent of residents say they get more exercise, and downtown revenue has increased by two-thirds.

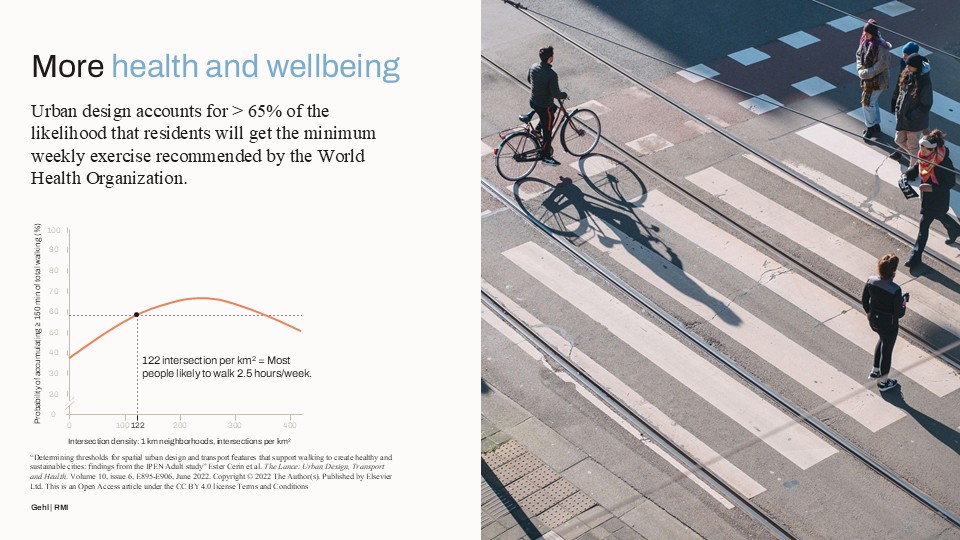

The co-benefits of climate-aligned urbanism are many, ranging from better health to more equitable economic opportunity. Walkable urban design alone can account for more than half of the likelihood that residents get the minimum weekly exercise recommended by the World Health Organization. Because walking and cycling require little to no investment from users, walkable neighborhoods provide the equivalent of a $5,000–$10,000 living expense subsidy, freeing up personal income for other purposes.

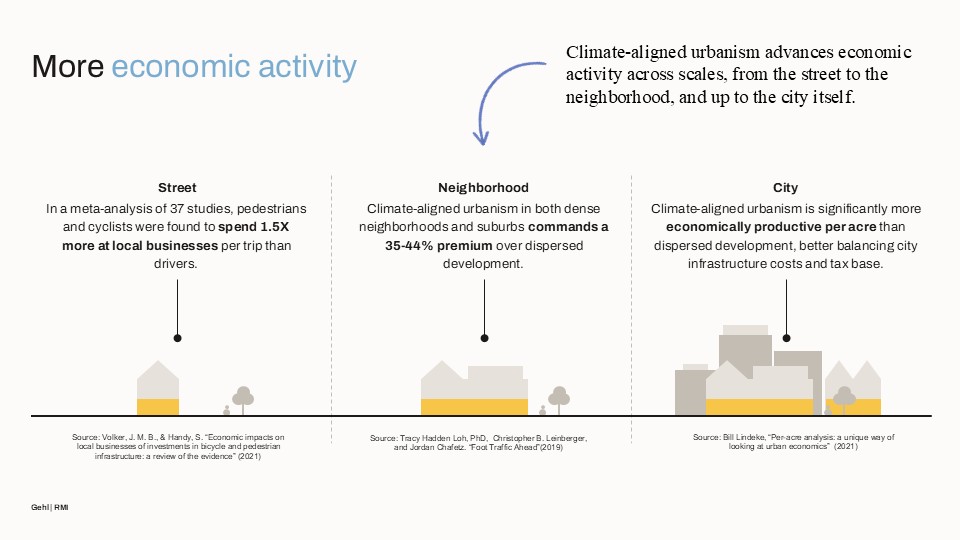

Dense, walkable neighborhoods are also more economically productive per acre, see 1.5 times more spending per visit, and have a 35–44 percent premium on real estate value over auto-oriented alternatives. Given the lower cost of infrastructure per resident in denser neighborhoods, this higher productivity provides a more sustainable long-term tax base to maintain that infrastructure.

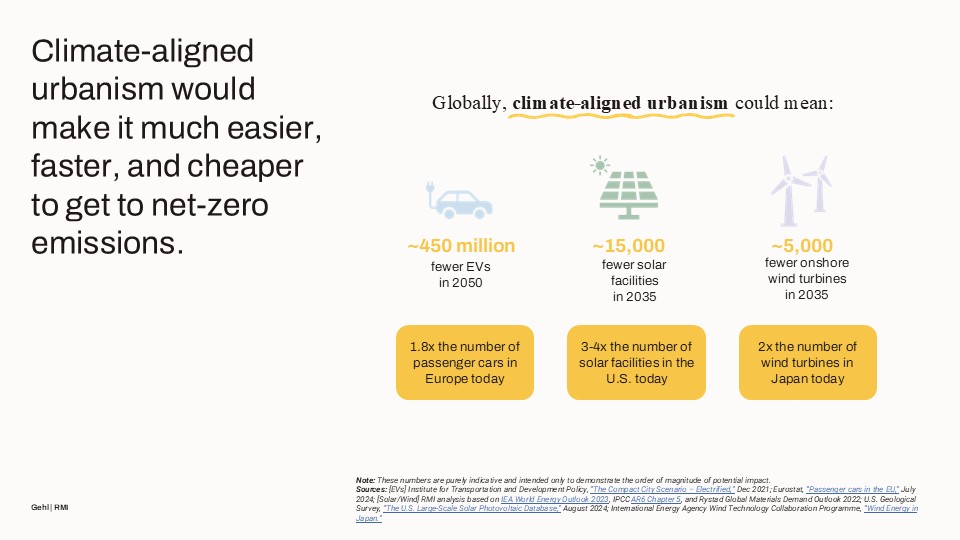

Achieving better urban form is one of the most powerful things we can do for the climate. And furthermore, if we build cities right, we will have to build a lot less of the other things we need to get to net zero. We will need fewer EVs, solar farms, wind turbines, batteries, and land (and need to fight fewer siting and permitting battles) — making the energy transition faster, easier, and cheaper. And it means greater health, improved equity, and stronger economic development.

Climate-aligned urbanism offers an abundant, positive life — not scarcity — and a blueprint for a just, prosperous, and irresistible urban future.