The Carbon Crediting Data Framework

A blueprint for a more interoperable carbon market

Executive Summary

The voluntary carbon market (VCM) struggles with how to most effectively catalyze finance towards high-integrity climate solutions for a simple reason: every carbon credit contains climate impact data that is locked away in static and dense PDFs and scattered across different stakeholders and disconnected processes. This disjointed data landscape drains time and resources. Project developers can spend up to 60% of their time managing duplicative data requests, while buyers can spend more than a year completing due diligence for just one project.[1] These inefficiencies drive up transaction costs, embed conflicts of interest among market actors, and undermine or delay investments to reduce or remove emissions. Overall, they raise questions about trust and quality in the market.

Recognizing these data challenges, RMI's Carbon Markets Initiative (CMI) developed the the Carbon Crediting Data Framework (CCDF)— a practical four-piece public toolkit to organize, standardize, and share carbon crediting data more effectively:

- Executive report (this document), which explains the context and contents of the CCDF to inform applicability to team needs

- Implementation spreadsheet, which details the core data fields in an Excel format[2]

- Technical documentation, which serves as a bridge between the Excel and JSON, and is a more human-readable version of the content in the JSON file

- JSON schema, which supports the integration with other platforms and software products

The CCDF synthesizes data requirements from more than 160 sources, including VCM methodologies, data-related best practices, and expert interviews to define a common language and structure for carbon crediting data and is aligned with industry-wide criteria for high-quality credits. The CCDF structure organizes specific data categories, sub-categories, and fields based on where they fit in the project lifecycle.[3] The published version provides standardized fields and metadata for 570 individual data fields, grouped in at least 22[4] categories and 48 sub-categories (depending on the methodology in use) to denote a project's emission and socio-environmental performance (See Exhibit ES-1).

Exhibit ES-1: Overview of the CCDF structure

|

TIER 0

Pre-Registration

|

TIER 1

Validation Status

|

TIER 2

Verification Status

|

TIER 3

Innovation & Ambition

|

|

Project Design

Project Details

Project Approach

Location Details

Disclosures

Organization Overview

Entities Involved

Location Compliance

Labor Rights

Carbon Rights

Socio-economic Due Diligence

Involuntary Displacement

Stakeholder Analysis

Benefits Sharing

Ecological Due Diligence

Air Quality

Biodiversity

Soil Health

Water Quality

and Availability

|

Validation

Results

Eligibility Requirements

Methodology-Specific Fields (customizable)

Project scale

Methodology-specific

Overview

Baseline Scenario

Description of Project Scale

Methodology Agnostic Overview

Methodology-Specific Fields

Additionality Analysis

Additionality Overview

Additionality Tests –

Evidence and Results

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)

LCA Overview

LCA Results

Greenhouse Gas Accounting

Boundary

System Boundaries

Spatial Boundaries

Projects' Credit Quantification*

Carbon Quantification

Buffer Estimates

Leakage Estimates

Forecast Estimation on

Emissions Reductions

and/or Removals

Uncertainty

Risk Management

Durability

Data and Monitoring

MRV Plan

Data Handling Plan

|

Verification

Results

MRV

Status/Update

Projects' Credit Quantification*

Actual Collected Data

(Values/Results)

Durability

Status of Reversal Events

Socio-Economic Impacts

Involuntary Displacement

Stakeholder Participation

Workforce and Capacity

Building Impacts

Economic, Fiscal, and

Benefits Sharing Impacts

Health and Sanitation

Ecological Impacts

Air Quality Impacts

Water Quality Impacts

Water Availability Impacts

Biodiversity Impacts

Soil Impacts

Marine and Coastal Health

Noise Pollution

Consequential Development

Impacts

|

Sustainable Development Goals

SDGs Supported by the

Project

Key Differentiators**

Specialized Core Benefits

Certifications (for e.g.,

gender credits, biodiversity

credits, water credits, etc.)

Citizen Science Initiatives

Innovations in MRV

Advanced Risk Mitigation and

Adaptation Strategies

Climate Finance Innovation

Novel Technologies

|

The data framework fosters data integrity, transparency, and efficiency across digital and manual systems. Early adopters, like RMI's technical partner Centigrade, are using the CCDF to improve market transparency and make data-driven climate impacts easier to verify. CMI is also applying lessons learned in our role as co-chair of the Carbon Data Open Protocol's (CDOP) Technical Working Group. CDOP is a coalition of over 50 VCM stakeholders striving to build a unified data schema to enable interoperability within the VCM.

In releasing the CCDF toolkit, we invite sustainability leaders, project developers, data providers, and platform builders to apply it in their work, contribute insights, and join a growing community of VCM stakeholders working to improve data standardization, transparency, and reliability in the market. Together, we can build a more reliable data foundation for the VCM and unlock the full potential of climate finance to deliver real, measurable, and trusted impact.

Chapter 1: A Cumbersome Market Without a Shared Data Blueprint

1.1 The costs of data fragmentation

The VCM has the potential to direct transformative volumes of global climate finance toward nature-based solutions, low-carbon technologies, and community-driven climate action, but this potential is undermined by data that is inconsistent, inaccessible, and difficult to collect, exchange, and analyze.

This market failure makes it difficult for participants to confidently assess quality. In nearly every transaction, stakeholders must navigate a disjointed maze of information in static documents, spreadsheets, proxy metrics, and instinctual judgment calls because developers and registries don't have a universal language or structured format for project data.

In interviews conducted by RMI's CMI, stakeholders repeatedly cited this data fragmentation and opacity as a barrier to scale. Project developers can spend up to 60% of their time managing and responding to requests from market actors for project data, while buyers can spend up to 18 months on due diligence for a single project. Both project developers and buyers pay between $15,000 and $50,000 per service provider (lawyers, ratings agencies, dMRV providers, etc.) to prove that the project will generate the promised emissions impact or to resolve data-related quality risks. Depending on the project, this can quickly drive data-related transactions costs above $100,000 per project. Until the VCM can reliably organize, surface, exchange, and analyze credit-level data — thus reducing these data-related costs — the VCM will struggle to deliver real and scalable climate impact.

Chapter 2: The Carbon Crediting Data Framework (CCDF)

2.1 The CCDF toolkit

The CCDF Toolkit includes four distinct tools, each tailored to different users and applications (see Exhibit 1). The first two formats are for non-technical users. For example, this report and the implementation spreadsheet will provide brokers or VCM project-level or product teams with detailed explanations of its substance and capabilities. These tools will help each team understand whether and how the CCDF is relevant to their data-related challenges. Software engineers can use technical documentation and JSON Schema to build integrations with other platforms or software related to project data.

Exhibit 1: Four tools in the carbon crediting data framework toolkit

| Resource | Description | Audience | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Executive Report | Narrative and structural overview | All VCM stakeholders: from senior leaders to individual contributors | Explains the context and contents of the CCDF to inform applicability to team needs |

| 2. Implementation Spreadsheet | Project-level data spreadsheet | Brokers, project developers or VCM-facing product teams | Details the core data fields in a tangible and functionable format |

| 3. Technical Documentation | Human-readable schema logic | Software engineers, implementation teams | Serves as a bridge between the Excel file and the JSON, providing a more human-readable version of the JSON content |

| 4. JSON Schema | Human- and machine-readable code | Software engineers | Supports integration with other platforms and software products. |

Upon implementation, the CCDF can support:

- Buyers and investors, who need clean and comparable data to make informed decisions, can use the CCDF to efficiently gather data and assess credit quality.

- Project developers, who rely on measurable impact, can use the CCDF to build a transparent and verifiable, data-driven story, while also streamlining data sharing with other actors.

- Verifiers and validators, who depend on structured data inputs, can use the CCDF to more efficiently access relevant project data, thus expediting their process.

- Ratings agencies, marketplaces, and independent service providers, which are looking for interoperability, can use the CCDF to build specialized tools (such as for socio-environmental indicators) that conform to a common language.

- Registries and platforms, which are building more dynamic and interconnected systems, can integrate the CCDF as a common layer to facilitate greater data sharing.

- Civil society and communities, which often hold the power to dictate long-term project success, can use the CCDF to provide transparency for how projects and benefit-sharing agreements are designed, evaluated, and financed.

Centigrade, a data utility, has implemented these tools and is using them to visualize the climate impacts of 6 million credits from 25 projects, spanning cookstoves to Direct Air Capture (DAC). Their case studies, in Chapter 5, demonstrate how these tools can unlock faster due diligence, real-time MRV integration, and more equitable access to innovative project developers.

2.2 The CCDF connects the dots between project-level data and market-wide credit quality initiatives

Quality is the most widely debated concept in the VCM. At a high level, all stakeholders agree that high-quality credits — and the carbon crediting projects that issue them — must be real, additional, durable, verifiable, deliver social and environmental benefits, and be supported by strong governance, transparency, and safeguard processes. These shared principles are vital components of integrity.

All quality expectations come from the guidance and influence of different stakeholders. Methodology developers, standards bodies, service providers, and regulators all shape VCM-wide expectations for quality through the lens of their own role, mandate, or area of expertise. While their frameworks vary in depth and breadth, they tend to cluster around four broad themes: legal and governance rigor, programmatic transparency, climate performance, and social and environmental impact. These recurring themes reflect a growing alignment around core quality concepts, but not necessarily around what project-level data is needed to support quality claims and how that data should be defined and structured.

In practice, all quality is ultimately determined at the project level. To connect the dots between high-level quality principles and granular project data, the VCM needs consensus on:

- What data points are needed across the full carbon project life cycle,

- What data points are needed to assess credit quality,

- How that project data should be formatted and organized, and

- How data suppliers and users can most effectively exchange that data.

The CCDF responds directly to this need. Building on existing quality initiatives, it identifies key project-level data requirements across all quality dimensions (see Box 1 and section 3.1). Ultimately, the CCDF provides a common language and toolkit the market can use to identify, describe, and organize project data as it flows through the VCM ecosystem.

Box 1: How the CCDF aligns with other efforts across the VCM

Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market (ICVCM): A VCM governance body that establishes high-level Core Carbon Principles (CCPs) and quality criteria at the methodology level. The CCDF supports these by surfacing the project-level data that upholds the CCPs.

InterWork Alliance (IWA): A standards-setting body under the Global Blockchain Business Council that defines token standards and data taxonomies. The CCDF extends this structure to include detailed project-level disclosures relevant to due diligence.

Carbon Credit Quality Initiative (CCQI): A multi-stakeholder platform led by the Environmental Defense Fund (EFD), World Wildlife Fund (WWF), and Oeko-Institut, CCQI gives stakeholders a credit scoring methodology to evaluate quality at the credit level. Its criteria have informed the CCDF's definitions, design, and depth at the project data level.

Climate Action Data Trust (CAD Trust): A World Bank-backed platform that aggregates registry-level metadata (e.g., project ID, country, and methodology) across standards. The CCDF complements this by tracking more granular data on how individual projects are implemented, verified, and monitored over time.

Carbon Data Open Protocol (CDOP): A coalition bringing together more than 50 VCM stakeholders to optimize the VCM through data harmonization. The CCDF serves as an input to the shared CDOP schema, which will ultimately support greater standardization, transparency, and interoperability across the market.

The CCDF doesn't aim to provide a new definition of quality. Instead, it aims to make the full universe of project-level data visible and provides the bridge that helps market participants link existing high-level market quality principles with project-level realities. Without the CCDF's structure, carbon crediting data risks being abstract, incomplete, and unverifiable. By clarifying project-level data needs, the CCDF strengthens existing quality efforts, giving users a practical starting point to assess credit quality more holistically and confidently.

Chapter 3: CCDF Methodology and Design Principles

3.1 Methodology overview

The CCDF aims to bring structure to the vast universe of carbon credit data. It is a synthesis of more than 160 sources that set the standards, best practices, and innovations regarding carbon crediting data in the VCM.[5] The CCDF's value lies in standardizing and translating the details and interconnections among these sources into a comprehensive, coherent, and interoperable format (see more detail in Chapter 4).

The emissions-related fields are an integration of the data requirements in the prevailing guidance from the institutions that define the current VCM. We start by integrating the IWA's Voluntary Ecological Markets Taskforce with specific requirements from the methodologies, institutional policies, and rulebooks of major standard bodies,[6] including Verra, Gold Standard, American Carbon Registry, Climate Action Reserve, and Puro.earth.[7] We also incorporated the project-specific criteria from quality initiatives such as the ICVCM's CCPs, CCQI, and from influential industry templates, such as Frontier's public Request for Offtake Proposals.[8]

On the socio-environmental (SE) side, we reference the safeguards used by a wide range of international finance institutions (IFIs), such as the World Bank Group (WBG) and regional multilateral development banks, multilateral climate finance institutions, such as the Green Climate Fund, and industry-shaping efforts, such as the Taskforce on Nature-Related Financial Disclosures and Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund.[9] We also incorporate the criteria from compliance frameworks like the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA).[10]

3.2 Translating socio-environmental data into a harmonized format

The CCDF treats emissions and SE impacts as integral components of credit quality. In contrast to most reporting templates, which treat SE impacts as optional add-ons or "co-benefits," the CCDF embeds SE data directly into the framework as "core benefits" central to a project's design, delivery, and long-term success.

To create the CCDF's emissions side, we had no shortage of VCM-specific frameworks, particularly from the registries, to reference, analyze, and synthesize based on points of convergence on how VCM projects can define, quantify, and measure climate impact. The framework incorporates each registry's institutional policies, which also spell out the respective standard's SE requirements. Typically, these requirements ensure that projects are not actively harming local communities, but they rarely set best-practice expectations for how projects can or should be tracking non-carbon impacts.

The SE guidance that does exist within the VCM registries and standards is highly generalized and lacks standardization. For example, all standards have basic requirements related to labor rights and the protection of workers, compliance with local laws, and avoiding involuntary displacement, but each registry uses different questions to assess compliance with these requirements and accepts answers in different formats. This broad guidance struggles to capture the complexity and granularity inherent in environmental and community impacts or to set data-driven expectations on how to quantify such impacts. To go beyond these do-no-harm disclosures, project developers must seek out complementary SE standards (such as W+ for measuring women's empowerment or WRI's Volumetric Water Benefit Accounting Framework) at their own discretion.[11]

The result is a complicated, confusing maze of potential guidance for how projects can or should incorporate SE activities into their activities or quantify their overall SE impact. This maze leaves SE considerations scattered in rigor across different standards, hard to quantify or verify, and thus hard to compare across project types.

The SE guidance and frameworks that do set best practices or establish standards for quantifying impact come from outside the VCM. They have roots in the biodiversity credit market, international development finance ecosystem, and multilateral climate finance institutions. Although the project activities financed through the VCM and through these other avenues can be similar, carbon crediting projects are subject to different governance and accountability mechanisms, which means these more rigorous SE frameworks had to be adapted to fit the VCM ecosystem.

CMI took on this adaptation challenge within the CCDF. We started by compiling existing VCM guidance from the registries and leading practices from development bank safeguards into the CCDF structure to set a baseline for the do-no-harm approach.[12] We then integrated the existing best practices on how to quantify impact for each SE category. This research came from civil society organizations, international humanitarian groups, the United Nations, environmental scientists, and industry leaders.[13] We also incorporated core benefits for specific project types, particularly for nature-based projects, to ensure that the CCDF fully captured the range of potential SE impacts. This approach ensures the CCDF accommodates both the minimum expectations and prevailing best practice on how carbon crediting projects could be measuring SE-related impacts for the duration of their operation.

Exhibit 2 presents four sample projects[14], each representing a different project type (Direct Air Capture, REDD+, mangroves, and cookstoves), to illustrate how project developers can use the CCDF to report their stakeholder participation activities. The CCDF’s consistent fields help developers share comparable details while still capturing each project’s actual activities. These examples are illustrative only. In practice, responses will vary from project to project — even within the same project type — depending on the project’s context, design, capacity, and approach to stakeholder engagement.

| CCDF Fields | DAC | REDD+ | Mangroves | Cookstoves |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Community Engagement (What groups are the subject of focused stakeholder outreach?) |

Residents near facility; city council representatives | Indigenous communities; tribal council; forestry department | Local cooperatives; national coastal management authority | Village leadership council; women's health NGO |

|

Engagement Frequency (Frequency of stakeholder engagement meetings and consultations?) |

Biannual in-person town halls open to the public | Twenty 1:1 landowner meetings during planning phase | Quarterly workshops via NGO partners | Monthly community assemblies open to the public |

|

Communication Channels (Does the project use tailored communication channels to keep in touch with and communicate relevant project news to stakeholders?) |

Yes – Project updates via email listserv | Yes – Community WhatsApp group; monthly check-ins with community liaison officers | Yes – Weekly check-ins with community liaison officers | Yes – Monthly household visits for each project household |

|

Grievance Mechanism (Is there a publicly available grievance reporting mechanism? How have reported grievances been resolved?) |

Yes – Re-routed transport routes in response to community noise concerns | Yes – Updated buffer zone maps based on traditional land use areas | Yes – Adjusted restoration schedule to avoid planting during peak harvesting season based on fisher feedback | Yes – Adoption of female-designed farming tools to address inclusion-related feedback |

|

Gender Consultation (Does the project measure gender performance indicators? Are gender-sensitive consultations conducted?) |

Not currently tracked; limited outreach to woman's groups | Yes – Literature review conducted; continuous monitoring of female-owned land plots | Yes – Pay equity and discrepancies monitored; input from women's fishing collectives on harvesting limits | Yes – Gender-sensitive focus groups in local dialects; findings anonymized and shared with domestic statistics service |

|

Data Privacy (What privacy protections for Indigenous peoples and local communities are implemented?) |

No Indigenous data collected | Data use governed by Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) protocols | Maps and community names anonymized unless explicit consent given | Household survey data stored locally with community oversight board |

In the hands of a project developer, the CCDF's consistent disclosure format allows them to share relevant information in ways that reflect their own operational and social realities. For reviewers or investors, this consistency allows for easier comparison across projects and clearer insight into how projects incorporated local knowledge and concerns. Since the CCDF incorporates fields that cover both current VCM standards and emerging best practices, it allows for SE quality judgements to be better grounded in detailed evidence and shifts the VCM towards better valuations of long-term sustainability.

3.3 CCDF's core design principles

- Consistency in data structure: The CCDF ensures that credit buyers, project developers, and auditors see the project information in uniform and predictable formats.

- Flexibility across project types: The CCDF can be adapted to include data requirements from different methodologies and stages of project maturity.

- Standardized metadata for interoperability: Each CCDF field is tagged with metadata, rendering consistent labeling and preparing the data for integration across digital platforms and workflows.

- Alignment with data rules: Every CCDF field follows three data rules that define its nature, format, and reporting requirements.[15]

3.4 Practical example: How these principles informed the durability fields

Exhibit 3 shows how these principles shaped the durability portion of the CCDF. Durability refers to how long the project plans to store carbon in natural or engineered systems, such as trees, soil, geological formations, or other carbon sinks and the risks the project activities or impacts will be reversed before the planned project duration.[16] Risks to durability can stem from natural events like wildfires, or from how a project is planned, monitored, and maintained over time. Yet, the data behind durability claims is often disorganized or incomplete, making it hard for stakeholders to either build a full picture of durability risks or to compare such risk across projects.

Exhibit 3: Applying the design principles to durability data

| Common challenge: Each standard treats durability and reversal risks differently | ||

|---|---|---|

| Design Principle | Explanation | CCDF Solution |

| Principle 1: Consistency |

All projects are prompted to answer a common set of questions:

|

The CCDF defines a common set of fields that appear for all projects. It ensures that standard project information is organized in a predictable layout that enables comparison. |

| Principle 2: Flexibility |

Response options vary based on project type:

|

The CCDF accommodates the VCM's project diversity – allowing each project to answer based on its unique data needs and contexts. |

| Principle 3: Standardized Metadata |

Each field is tagged with metadata to support integration and clarity:

|

The CCDF provides internal formatting for individual data fields to ensure clarity and legibility for integration, regardless of project type. |

| Principle 4: Data Rules |

Durability fields are structured using data rules:

|

The CCDF standardizes durability information through structured data rules to increase data reliability and usability across diverse project types. |

These design principles help the CCDF provide enough structure to support data interoperability and enough flexibility to reflect the uniqueness of carbon crediting projects. Centigrade is using the CCDF to bring data from a suite of projects — consolidating fragmented and static information into a dynamic source of truth that reflects projects’ depth and nuance — thereby demonstrating the real-world functionality of these principles (see Chapter 5 for specifics).

Chapter 4: Structure, Data Fields, and Interoperability in the CCDF

4.1 Tier structure and content

The CCDF uses four tiers (see Exhibit 4) to structure the data based on its most applicable stage in the lifecycle of a carbon credit project.

Exhibit 4: CCDF tiers by crediting stage and primary user

Each tier then contains categories, sub-categories, and data fields that align to a project's current stage and chosen methodology. This structure gives each tier a distinct purpose:

- Tier 0 – Pre-Registration Data: This tier focuses on initial project design and governance, with fields related to project location, project approach, and its projected socio-environmental impacts (see Exhibit 5). This data helps assess whether a project meets basic certification requirements as these fields are methodology-agnostic. This data tends to be most useful for registries, early-stage project developers, and validators.

- Tier 1 - Project Validation Stage (Forecasted Data): This tier focuses on the specifics of the project design that inform forecasts of credit quality at the validation stage. More of this data is methodology-dependent, as it covers carbon accounting, baseline, and project eligibility requirements.[17] This forecasted data can be beneficial for validators, buyers, and investors as they begin to explore pre-purchase agreements.

- Tier 2 – Project Implementation Stage (Verification Data): Tier 2 data provides actual quantifications of a project's measured, monitored, and verified impact on greenhouse gas emission, socio-economic, and ecological metrics. Groups like verifiers, MRV providers, and data or quality evaluators can use this information to assess projects' actual performance data against their forecasted plans.

- Tier 3 – Data-Driven Innovation and Ambition: Tier 3 is meant to capture data-related innovations that exceed current methodology or registry requirements. For example, project developers could use this tier to showcase their data-related innovations, such as stacking biodiversity or gender credits or incorporating real-time MRV (beyond methodology requirements). Buyers could use this to make customized RFP requests, should they desire any data beyond what is disclosed in Tiers 0 to 2.

4.2 Data categories, sub-categories, and fields

Within each tier, project data is organized into categories, sub-categories, and fields. Each field is a specific data point to capture the critical information for the sub-category. Thus, the granularity and metadata of the fields give the data framework its true depth and usefulness. Exhibit 5 shows this structure for Tier 0.

Exhibit 5: Overview of CCDF structure at tier 0

Every data field has four standardized metadata tags. These tags ensure that the data is consistently labeled, clearly described, and interoperable, regardless of whether the data is managed manually or digitally. Each field contains:

- A standardized name ("Label"): the specific information being requested.

- A clarifying note ("Description"): a concise explanation to reduce ambiguity or subjectivity of a data field, when needed.

- Data type ("Type"): the format for inputting data (e.g., array, string, object).

- Enumerated choices ("Options"): a list of predefined choices (when applicable) based on the data type and structure.

Exhibit 6 shows how the metadata tags operate for non-monetary benefit-sharing fields.

Exhibit 6: Metadata tags for non-monetary benefit sharing (tier 2 subcategory)

| Label | Description | Type | Options |

|---|---|---|---|

| The project engages in benefit sharing aside from financial payments | Examples of non-financial benefits can include the sharing of products or goods, technology transfer, and/or local infrastructure improvements | boolean | N/A |

| Non-monetary benefits implemented by the project activity | Non-monetary payment types adapted from definitions within the UN Nagoya Protocol | array |

|

| Description of non-monetary benefit sharing activities | High level summary of benefits shared that are not provided as an exchange of money | string | N/A |

| Non-monetary benefit sharing supporting documents | Evidence of agreement and distribution of non-monetary benefits | array | N/A |

Overall, the CCDF provides standardized fields and metadata for at least 570 individual data fields, grouped in upwards of 22 categories and 48 sub-categories, depending on the methodology in use (See Exhibit 7).

Exhibit 7: Overview of the CCDF structure

|

TIER 0

Pre-Registration

|

TIER 1

Validation Status

|

TIER 2

Verification Status

|

TIER 3

Innovation & Ambition

|

|

Project Design

Project Details

Project Approach

Location Details

Disclosures

Organization Overview

Entities Involved

Location Compliance

Labor Rights

Carbon Rights

Socio-economic Due Diligence

Involuntary Displacement

Stakeholder Analysis

Benefits Sharing

Ecological Due Diligence

Air Quality

Biodiversity

Soil Health

Water Quality

and Availability

|

Validation

Results

Eligibility Requirements

Methodology-Specific Fields (customizable)

Project scale

Methodology-specific

Overview

Baseline Scenario

Description of Project Scale

Methodology Agnostic Overview

Methodology-Specific Fields

Additionality Analysis

Additionality Overview

Additionality Tests –

Evidence and Results

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)

LCA Overview

LCA Results

Greenhouse Gas Accounting

Boundary

System Boundaries

Spatial Boundaries

Projects' Credit Quantification*

Carbon Quantification

Buffer Estimates

Leakage Estimates

Forecast Estimation on

Emissions Reductions

and/or Removals

Uncertainty

Risk Management

Durability

Data and Monitoring

MRV Plan

Data Handling Plan

|

Verification

Results

MRV

Status/Update

Projects' Credit Quantification*

Actual Collected Data

(Values/Results)

Durability

Status of Reversal Events

Socio-Economic Impacts

Involuntary Displacement

Stakeholder Participation

Workforce and Capacity

Building Impacts

Economic, Fiscal, and

Benefits Sharing Impacts

Health and Sanitation

Ecological Impacts

Air Quality Impacts

Water Quality Impacts

Water Availability Impacts

Biodiversity Impacts

Soil Impacts

Marine and Coastal Health

Noise Pollution

Consequential Development

Impacts

|

Sustainable Development Goals

SDGs Supported by the

Project

Key Differentiators**

Specialized Core Benefits

Certifications (for e.g.,

gender credits, biodiversity

credits, water credits, etc.)

Citizen Science Initiatives

Innovations in MRV

Advanced Risk Mitigation and

Adaptation Strategies

Climate Finance Innovation

Novel Technologies

|

Ultimately, the CCDF was designed to be digitized and implemented — a feat first accomplished by Centigrade. Centigrade's case studies demonstrate how a digitized data framework can drive efficiency, interoperability, and improved quality across the VCM (see Chapter 5). For more information about other ways to implement the CCDF, see Chapter 6.4 or contact us at carbonmarkets@rmi.org.

Chapter 5: Lessons from Centigrade’s Implementation of the CCDF

5.1 Technical implementation

Centigrade, a data utility for carbon crediting data, implemented our CCDF in a digital format, then built additional capabilities to digitize, organize, and visualize project data (see Exhibit 8). Centigrade offers three functionalities for different VCM users. Project developers enter project information into a web form, a structured template designed to standardize and organize key data fields. Buyers and other stakeholders access the view page, which presents the information entered in the "Form" in a user-friendly format optimized for evaluating project details and performance. Centigrade also has an API to enable direct sharing of project data between the Centigrade platform and other VCM stakeholders, such as dMRV providers, raters, insurers, buyers, and others.

Exhibit 8: What Centigrade's software does and the value it provides

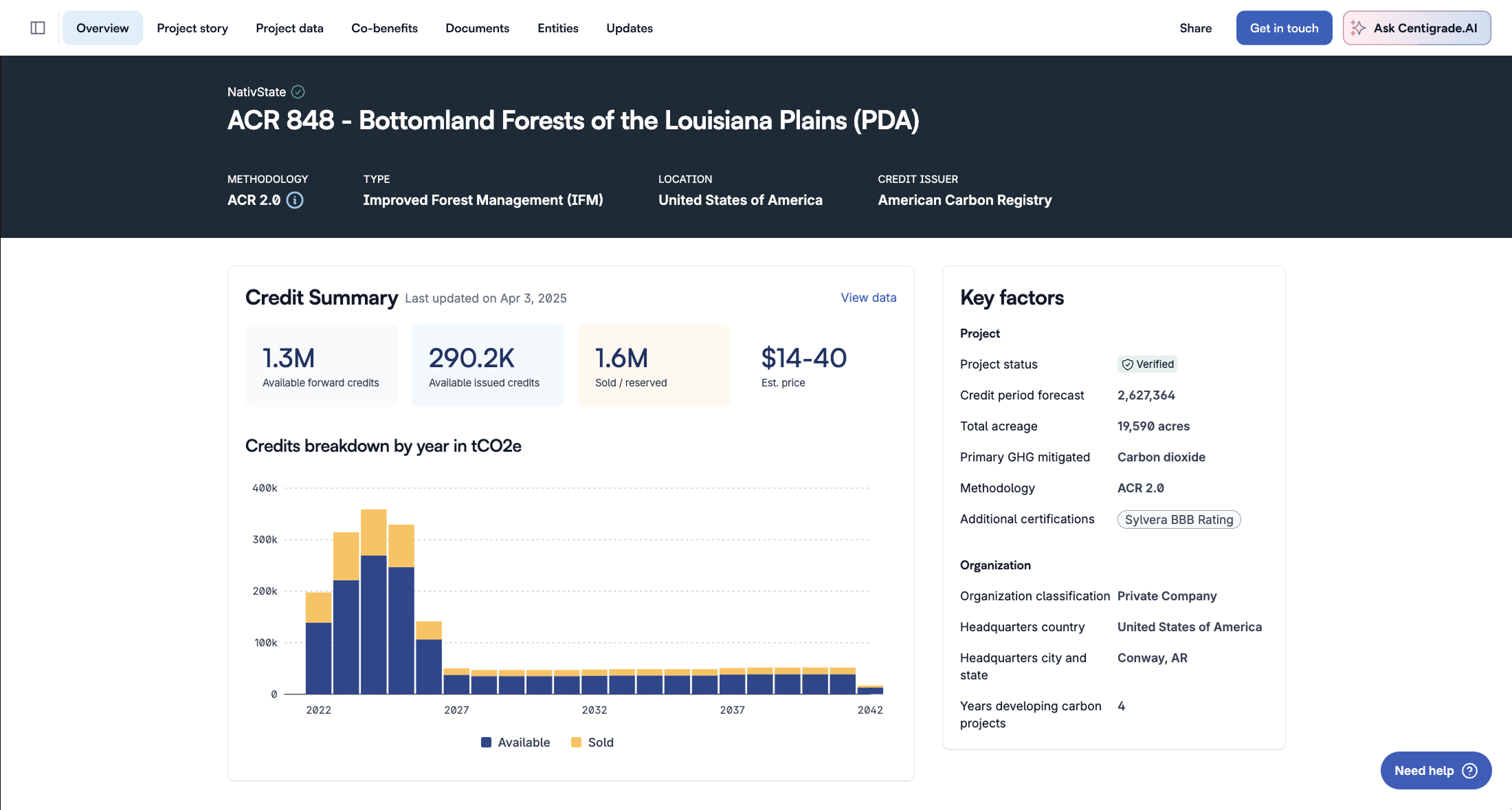

Exhibit 9 shows how the project developer NativState used Centigrade's Form (to input data) and View (to show said data) to highlight key details and features for its ACR848 project.

Exhibit 9: NativState's ACR848 project on Centigrade's view

Centigrade's platform uses the CCDF schema to support structured data uploads for at least 16 distinct VCM methodologies or project types[18], including for projects that have yet to select a methodology. For these projects, Centigrade uses the methodology-agnostic portion of the CCDF (i.e., the tools released here) to help projects organize and demonstrate the data they do have.

5.2 How Centigrade is using the CCDF to help projects compete on data quality

In its pilot phase, Centigrade worked with at least 25 project developers, covering nearly 6 million credits across numerous project types. Each developer used the platform to record their project data in CCDF-aligned fields.

The following case studies illustrate how different market actors are interacting with Centigrade to address longstanding, market-wide gaps in data efficiency, visibility, and traceability.

Expediting ratings of credit quality

When project data is scattered across dense, static, or unstructured documents, credit quality evaluators struggle to access project information, which slows down review processes (see Box 2). A project developer and ratings agency collaborated with Centigrade to share critical data — thus shortening and improving clarity for all stakeholders.

Box 2: More efficient data sharing between a project developer and ratings agency

| Challenge | Typically, data exchanges between developers and ratings agencies require repeated emailing of PDFs, spreadsheets, and other documents — often leading to duplicative requests, inconsistent terminology, multiple versions causing confusion, and delayed reviews. Project information is scattered, making it difficult for ratings providers to quickly verify project claims. |

| How Centigrade helped | The developer uploaded their project data into Centigrade's CCDF structured fields, including key Tier 0 disclosures (e.g., project proponent, location, project type), supporting documentation, and linked metadata. The ratings agency accessed a dedicated Centigrade page, where all data was labeled, traceable, and contextually organized. Each field included direct links to original source documents, which eliminated the need for manual follow-up or clarification requests. |

| Takeaway | Structured and interoperable data, delivered through a CCDF-aligned interface, can reduce friction between developers and ratings providers. Centigrade, a neutral intermediary, can enable smoother and more transparent data exchange across VCM actors. Centigrade is exploring similar partnerships with ratings agencies and other service providers, based on specific data needs. |

Using the methodology-agnostic CCDF to help early-stage project developers

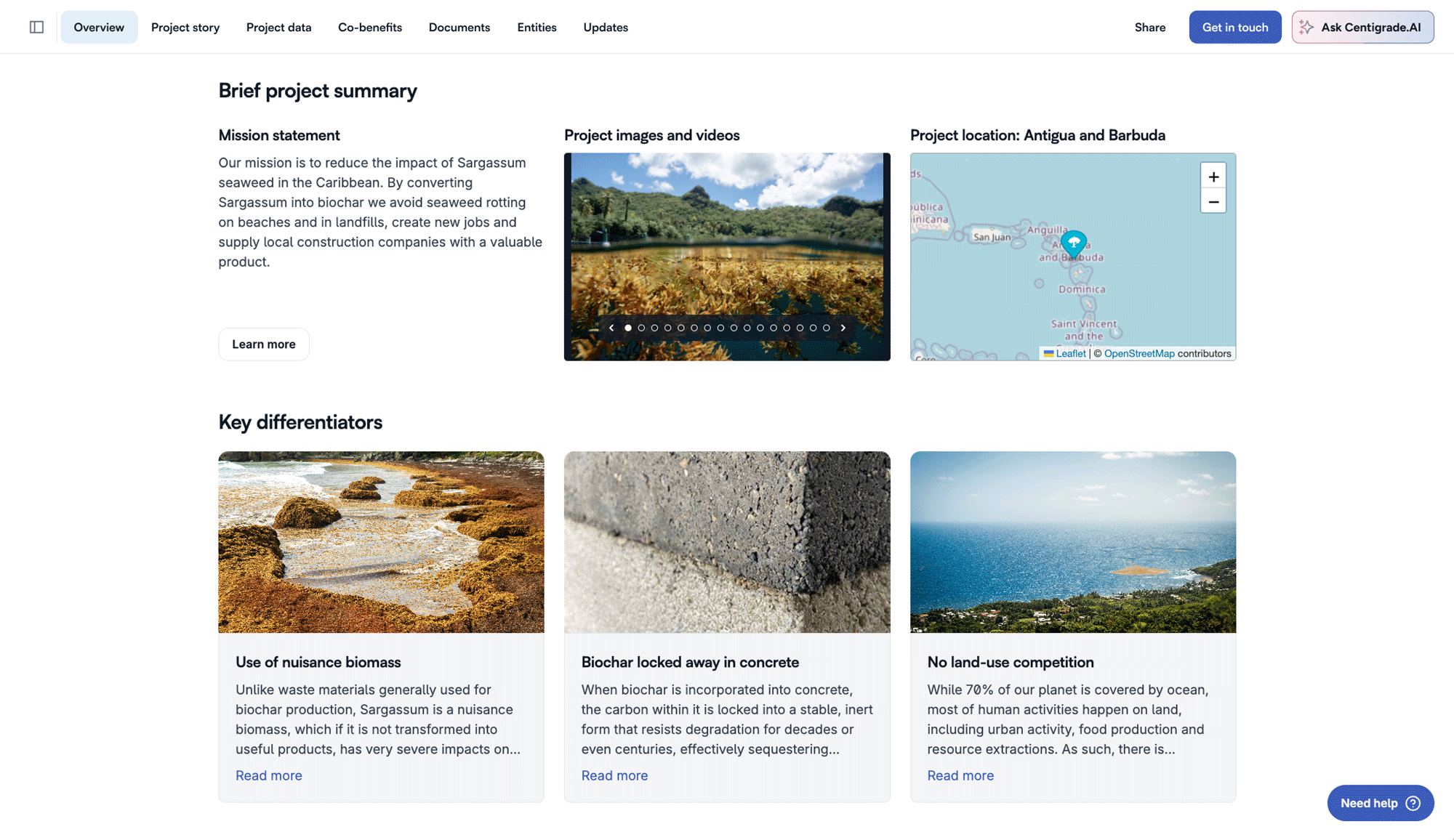

Many early-stage developers — especially those with newer methodologies or who have yet to select one — lack a standardized and transparent way to use data to show the impact of their projects, making it difficult to engage investors or gain traction in the market. Centigrade used the methodology-agnostic CCDF to help Deep Sky, Octavia Carbon, and Seafields demonstrate the data-driven potential of their project and expand their options for connecting with buyers and investors (see Box 3).

Box 3: Early visibility for breakthrough technologies

| Challenge | Enterprises, investors, governments, carbon advisors, and marketplaces all have differing carbon removal project evaluation processes and screening criteria to assess project quality and risk. Diligence involves finance, risk, audit, and procurement teams. When project data arrives as scattered PDFs, ad-hoc spreadsheets, or email attachments, internal reviews can't easily trace assumptions or reconcile terminology, causing weeks of back-and-forth and slowing momentum. This issue is especially acute for early-stage and innovative project developers, who may not yet have selected a methodology or completed validation. Many emerging approaches aren't yet covered by existing VCM methodologies, and project teams often face lean teams, limited resources, and tight timelines, making it hard to navigate the traditional certification pipeline. |

| How Centigrade helped | Centigrade used the CCDF to help project developers, including Deep Sky, Octavia Carbon, and Seafields, create structured project profiles and to highlight the project's top three differentiators (see Exhibit 10 for an example from Seafields). Each team populated key fields such as financial strategy, scale-up plans, MRV design, technical specifications, and investment analysis. They also uploaded supporting materials, including site photos and technical memos, and added project-specific context in the optional disclosure fields. Each team uses their Centigrade page as a single source of truth when sharing project data with external stakeholders. Centigrade helped Seafields streamline project documentation by providing CCDF fields aligned with verifier requirements, eliminating the need for their internal team to repeatedly cross-reference complex standards. Centigrade also offered insight into how similar project developers approached their MRV process — helping Seafields learn from more experienced practitioners. Octavia Carbon used Centigrade to speed up the due diligence process by labeling and contextualizing project data into a single, organized profile, thus reducing delays and duplicative requests during buyer engagement. Deep Sky used the platform to map their MRV, technical, and financial data into a centralized, traceable format, allowing buyers and government stakeholders to assess project quality more efficiently and to identify the details most pertinent to their internal processes. |

| Takeaway | Structured, interoperable data removes friction: Centigrade's organized fields and interactive platform make it easier and more transparent for project developers to understand which documentation is needed to advance through the process. Centigrade's neutral interface enables buyers, investors, and governments to interact with all available project data as they need for their internal due diligence process. The result is more streamlined project development, faster due diligence, clearer quality evaluation, and a shorter path to climate action. |

Exhibit 10: Seafield's project differentiators on Centigrade's platform

Visualizing real-time dMRV data on a project page

As digital monitoring, reporting, and verification (dMRV) becomes more prevalent, MRV data becomes further detached from static documentation, making it difficult for buyers or verifiers to trace how raw measurements connect to other components of project design and operation (Box 4). Centigrade has partnered with a project developer and dMRV provider to digitize all such data in a map on Centigrade's platform (see Exhibit 11) — offering a one-stop shop for how the projects are performing in real time.

Box 4: Visualizing dMRV and project design on Centigrade's platform

| Challenge | As market-wide expectations for transparency grow, many developers are adopting dMRV tools to collect site-specific or field-level data. However, most dMRV platforms offer raw data outputs without integrating that information with all other aspects of project activities. Buyers and verifiers thus struggle to trace how a specific data stream (e.g., from a cookstove sensor) relates to claimed emissions reductions or project-level co-benefit impacts. |

| How Centigrade helped | Centigrade partnered with the project's dMRV provider to stream digital data — i.e., sensor readings, usage logs, and geospatial metadata — onto the platform and then visualize it in near real-time (see Exhibit 11). The CCDF's structure helps Centigrade connect the technical measurements to the project's narrative context. Centigrade strengthened the project's data integrity by anchoring its claims to primary data sources and digital visualizations that exceeded what the dMRV platform alone could provide. |

| Takeaway | Centigrade strengthens the data integrity of projects by linking primary digital data sources directly to real-time, verified data streams. Such integration of Centigrade's CCDF-enabled capabilities, project needs, and dMRV functionalities can enable more credible and traceable claims of credit performance. |

Exhibit 11: Real-time monitoring for cookstoves using dMRV integration on Centigrade

Chapter 6: Building Off the CCDF to Drive Increased Interoperability, Transparency, and Trust in the VCM

In developing this CCDF toolkit — and learning from Centigrade's implementation — RMI's CMI has discovered four additional ways the CCDF structure and open-source collaboration can catalyze more interconnectivity, improved quality, and increased ambition across the VCM. We are releasing this toolkit as a product and an invitation so we can co-create, iterate, and apply these tools together. With your partnership, we believe the CCDF can:

- Build quality-focused collaborations to catalyze investment in high-integrity credits,

- Cultivate an open-source community to yield a unified VCM schema,

- Encourage data-related innovation and specialization by building out Tier 3, and

- Increase standardization and data integrity for socio-environmental metrics.

If these use cases resonate with you, if you have ideas for additional applications, or if you see ways to improve the CCDF toolkit, we would love to hear from you! Please share your feedback with us at carbonmarkets@rmi.org.

6.1 How quality-focused collaborations can catalyze investment in high-quality credits

Ultimately, all VCM actors are chasing the same outcome: verifiable data that demonstrates the project is generating high-quality credits. Ideally, to reach such a determination, market actors base their assessment on a comprehensive, exhaustive review of all available information about the project's design, planned activities, and actual impacts. Yet, in today's VCM, this feels like an elusive destination, with each gap or contradiction in the data landscape making it harder to collect or conduct a comprehensive assessment. This undermines the VCM's ability to identify and value high-integrity credits.

The CCDF offers a paved road through the complicated VCM jungle. Its depth allows users to understand the boundaries of what can or should be known about a specific project. Its structure enables the CCDF to be a granular map, helping users quickly locate that information and assessing the verifiable evidence that supports (or undermines) a project's quality claims. While the current version of the CCDF draws VCM-wide best practices and is aligned with existing quality initiatives, we know there is ample room for refinement, collaboration, and iteration.

6.2 How an open-source community could drive consensus and improved integrity in the VCM

We recognize that introducing another data framework into an already complex system risks further fragmentation. That's why the Carbon Credit Data Framework (CCDF) is designed as part of a broader movement toward convergence in the VCM. RMI is actively working to unify the ecosystem through open-source collaboration, coalition-building, and harmonization with other market initiatives.

One way we are doing this is by serving as co-chair of CDOP's technical working group. CDOP's diverse group of registries, ratings agencies, marketplaces, project developers, and data providers are collaborating on how best to harmonize sixteen distinct schemas into one unified schema. If successful, such a unified schema will serve as the connective tissue for greater transparency, interoperability, and trust across the VCM.

RMI's CCDF is one of these sixteen schemas. As co-chair, CMI is applying our expertise in data standardization, solutions-focused collaboration, and consensus-building to guide the harmonization process.

CDOP is on track to release an initial version of this schema at the 2025 New York Climate Week. This first release will focus on a subset of pre-registration data fields (i.e., a selection of the CCDF's Tier 0 data fields). Although this release represents a critical first step in a larger journey, it will validate CDOP's overall mission and collaborative approach. Beyond that launch, CDOP will continue expanding its membership, refining the technical schema, and establishing a long-term institutional home to sustain and scale the work.

As an organic, collaborative, and member-driven effort, CDOP's impact and overall success is intertwined with the expertise and commitment of its members. Every VCM actor has a critical perspective that can strengthen the CDOP effort. Whether you're ready to join the coalition or simply learn more, we'd love to hear from you!

6.3 How Tier 3's collaborative structure can encourage and harness data-driven ambition

Early on, we saw an inherent tension in our quest to standardize project-level data in a dynamic and innovative VCM: data standardization thrives on predictability, structure, and uniformity, but rapid innovation thrives on experimentation and creativity — and navigates ambiguity. The trends driving the VCM's dynamism - improved satellite and digital capabilities, advances in scientific capabilities and understanding, and evolving consensus on how "high-quality" is defined and measured — are redefining what the data landscape can provide.

Our Tier 3 accommodates this tension. It is an open and adaptable space where project developers, buyers, and other market participants can incorporate advances in data capabilities or project-related certifications that exceed tiers 0 to 2. For example, project developers could use Tier 3 to "stack" biodiversity, gender, and other beyond-carbon certifications on top of the carbon credits they have proven in Tiers 0 to 2. These specialized certifications have a data rigor and granularity for specific topics that exceed the CCDF's other tiers, so stacking them across the CCDF tiers would make it easier for market actors to use structured and comprehensive data to discern the legitimacy of such stacking, reduce concerns about double counting, and ensure the project's full impacts can be properly valued.

For now, Tier 3 remains open. We invite those who are exploring new data-driven innovations — including those related to biodiversity, social equity, digital MRV, or emerging benefit-sharing models — to get in touch.

6.4 How the CCDF can improve quality assessments of socio-environmental data

Most buyers desire projects that deliver measurable and verifiable benefits to nearby communities, particularly for nature-based projects in remote settings or those involving marginalized groups. Such benefits commonly include shared project revenues, expanded economic activities, healthier ecosystems (watersheds, soils, forests or other ecosystems), and a heightened attention to vulnerable demographics. However, due to the maze of SE guidance (see Chapter 3.2), many buyers find it simplest to select projects with "charismatic stories."

Throughout our research and consultations, we heard that the SE-specific portion of the CCDF could be a game-changer for projects with verified, data-backed SE impacts. In response, we will release the socio-environmental toolkit in the coming months. That toolkit will include an explanatory article,implementation spreadsheet, technical documentation, and JSON schema to help users assess SE data and integrate it into their decision-making processes.

We are shaping this SE toolkit with the community in mind. If you have ideas on use cases or how to make this framework most applicable to your region or project type, please reach out.

6.5 Call to action

Ultimately, for the VCM to reach its potential as a catalyst for financing transformative climate solutions, market actors need to be able to efficiently and clearly communicate the verified impacts of their projects using a digitized, standardized, and interoperable data framework. RMI is confident that the VCM can reach its potential — and is committed to building the open-source, technical ecosystem required to yield the necessary communications and market infrastructure. But an ecosystem cannot be built alone. We need collaborators to contribute to this effort. Your experience — whether navigating data gaps, piloting innovative projects, supporting co-benefits, or driving market transparency — is invaluable to an open-source ecosystem.

If you see opportunities to build on this work, spot areas for refinement, or simply want to explore how we can support your efforts, we'd love to hear from you at carbonmarkets@rmi.org.

Appendix

End Notes

[1] Based on interviews and research the CMI team conducted with project developers, service providers, and buyers between August 2023 and July 2025.[2]This Excel version contains the core methodology-agnostic CCDF. It does not include extensions tied to specific VCM methodologies. For the full version or a digital implementation, contact CMI or explore the Centigrade platform.

[3] A field includes a standardized name (Label) along with all the accompanying metadata. The metadata includes the Description (short explanation), Data Type (format for data input), and enumerated choices (pre-defined options, when relevant). See Chapter 4.2 to learn more.

[4] The CCDF includes 21 data categories in its methodology-agnostic version. This number may vary depending on the specific methodology, as some introduce additional data requirements.

[5] These sources included active VCM methodologies, GHG accounting guidance, registry policies and templates, environmental and social safeguards, public quality frameworks, and academic literature.

[6] We used the InterWork Alliance's Voluntary Ecological Markets Overview and Digital Measurement, Reporting & Verification (dMRV) Framework as foundational frameworks to guide how project- and credit-level data is structured in the CCDF. They informed our use of field definitions, claim workflows, and emerging approaches to automated MRV.

[7] We analyzed the flagship standards and rulebooks from Verra (VCS Standard, VCS Program Guide, VCS Validation Verification Manual, AFOLU Non-Permanence Risk Tool), Gold Standard (Principles and Requirements), the American Carbon Registry (ACR Standard, ACR Validation and Verification Standard, ACR Tool for Risk Analysis and Buffer Determination, ACR Buffer Pool Terms and Conditions), Climate Action Reserve (Reserve Offset Program Manual), and Puro.earth (Puro Standard General Rules) to extract required carbon data fields across the project lifecycle. These documents reflect current best practices and provide foundational guidance on how credits are designed, verified, and certified in the VCM today.

[8] We incorporated guidance from ICVCM's Core Carbon Principles Assessment Framework and Procedure and CCQI's Methodology for Assessing the Quality of Carbon Credits to align with industry-accepted quality criteria, and reviewed Frontier's Request for Offtake Proposals to identify emerging buyer and market expectations for carbon removal pathways. These documents represent evolving reference points for assessing the integrity and market readiness of carbon crediting projects.

[9] From the World Bank Group, we consulted the 10 Environmental and Social Standards (ESS) and their accompanying guidance notes and good practice notes, a publication titled Benefit Sharing in Practice: Insights for REDD+ Initiatives; and the IFC's Performance Standards on Environmental and Social Sustainability. From the MDBs, we consulted the Environmental and Social Safeguards/Requirements from the AfDB, ADB, EBRD, EIB, and IADB. We also analyzed AfDB's Policy Statement and Operational Safeguards, ADB's Gender Equality Results and Indicators, Gender Toolkits for energy and transportation, and the EBRD's performance requirements especially within land acquisition, involuntary resettlement, and economic displacement. From the Green Climate Fund, we referenced overarching environmental and social safeguards, as well as four operational project safeguard reports, country ownership, and indigenous people's policies. From the Taskforce on Nature Related Disclosures, we referenced guidance on the identification and assessment of nature related issues and best practices for disclosures. From the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, we consulted definitions of biodiversity hotspots.

[10] We referenced CORSIA emissions unit eligibility criteria, alongside guidance from the ICAO to help inform fields related to compliance regimes. Additionally, we also consulted other non-carbon specific compliance reporting regimes, such as those outlined by the Nagoya Protocol and Kimberly Process Certification scheme.

[11] Alongside the two mentioned frameworks, other complementary SE standards consulted include programs such as B Corporation accreditation, Forest Stewardship Council's FSC Principles and Criteria, Fairtrade's standards for pricing and hired labor, and Marine Stewardship Council's MSC fisheries standard.

[12] Environmental and social safeguards/requirements from Climate Action Reserve, Verra, American Carbon Registry, Gold Standard, Isometric, and Puro.earth were consulted. Safeguards within development banks were referenced across the World Bank Group, AfDB, ADB, EBRD, EIB, and IADB.

[13] On gender-based topics, we referenced Social Development Direct's gender-related guidance specific to the VCM, 2X Global's Gender and climate finance toolkit, W+ framework for measuring women's empowerment, various UN gender- responsive indicators tools, and the B Corporation's SDG Action Manger Tool. The International Institute for Environment and Development has published biodiversity credit schemes, which we used alongside biodiversity credit calculation indicators and metrics from Bloom Labs and guidance from SAVIMBO to inform biodiversity-related fields. We also reference erosion assessments from Global Forest Watch, wildlife connectivity guidance from WWF, soil indicators and taxonomies from the FAO, and additional peer-reviewed publications around environmental co-benefit accounting and monitoring. On the market side, B Corporation's impact assessments, Abatable's market research, Fairtrade's pricing and disclosure standards, and several UN resolutions surrounding nature-based accounting informed our work. Within the UN, we based our work on resolutions such as those governing free, prior and informed consent, general human rights, elimination of gender-based violence, and elimination of racial discrimination from agencies such as UN Women, UNHCR, UNEP, UNDP, and UNFCCC. For a full list of documents that informed this work, please see Works Consulted.

[14] The responses shown here are hypothetical examples provided for illustrative purposes only; actual reporting will differ based on the characteristics and practices of each individual project, even within the same project type.

[15] The three data rules are (1) Typological rules — define the classification of a data field, such as whether it is primary or secondary ; (2) Validation rules — define what a field must or must not contain, including whether it is required or optional; and (3) Logic rules — define how fields behave in relation to one another, such as showing or hiding fields based on earlier responses. These rules support adaptability, allowing each project to engage only with the fields relevant to its stage, design, or methodology.

[16] Durability is often used interchangeably with permanence, but the two focus on different aspects of how emissions are stored over time. Permanence refers to "the confidence in a project's carbon storage lasting 100+ years or more." See this explanation from Sylvera for more details.

[17] The published toolkit includes placeholders for these fields but does not include any methodology-specific fields. Please reach out to CMI or explore the Centigrade platform to see methodology-specific fields.

[18] Active methodologies in Centigrade's platform include: ACR Improved Forest Management (IFM) on Non-Federal U.S. Forestlands v1.3, ACR Improved Forest Management (IFM) on Non-Federal U.S. Forestlands v2.0, Leak detection and repair in gas production, processing, transmission, storage and distribution systems and in refinery facilities Version 4.0.0, Puro Standard Biochar Methodology Edition 2022 v3, Biochar methodology agnostic, Climate, Community & Biodiversity Standards, CLEAR Methodology for Cooking Energy Transitions, Gold standard Methodology for Metered and Measured Energy Cooking Devices v1.2, DAC methodology agnostic, Puro Standard Enhanced Rock Weathering v2, Puro Geologically Stored Carbon Edition 2024, Riverse Biochar Module, Gold standard Technologies and Practices to Displace Decentralized Thermal Energy Consumption (TPDDTEC), VM0033 Methodology for Tidal Wetland and Seagrass Restoration, v2.1, VM0042: Improved agricultural land management, VM0045 Methodology for Improved Forest Management v1.1, VM0047 Afforestation, Reforestation, and Revegetation, v1.0, VM0050 Energy Efficiency and Fuel-Switch Measures in Cookstoves, v1.0, and Other methodology agnostic. The Centigrade team routinely works with project developers to digitize additionality methodologies into the CCDF.

Works Consulted

2X Challenge. 2025. "2X Criteria Reference Guide — 2X Challenge." 2xchallenge.Org. 2025. https://www.2xchallenge.org/2x-criteria-reference-guide.2X Global. 2025. "Gender and Climate Finance Toolkit." 2X Global. 2025. https://www.2xglobal.org/climate-toolkit-home.

Abatable. 2024. "Which Methodologies Will Help Cookstoves Thrive? • Abatable." Abatable (blog). January 23, 2024. https://abatable.com/blog/which-methodologies-will-help-cookstoves-thrive/.

African Development Bank. 2025. "Environmental and Social Requirements." Text. African Development Bank. May 14, 2025. https://www.adb.org/who-we-are/environmental-social-requirements.

African Development Bank (ADB). 2013. "Policy Statement and Operational Safeguards." Volume 1. Issue 1. African Development Bank Group's Integrated Safeguards System. Tunisia: African Devlopment Bank (ADB). https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Policy-Documents/December_2013_-_AfDB%E2%80%99S_Integrated_Safeguards_System__-_Policy_Statement_and_Operational_Safeguards.pdf.

American Carbon Registry (ACR). 2018. "ACR Validation and Verification Standard v1.1" v1.1 (May). https://acrcarbon.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/2023.05.29-ACR-VV-Standard_V1.1_May-31-2018.pdf.

———. 2022. "Methodology for the Quantification, Monitoring, Reporting and Verification of Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reductions and Removals from IMPROVED FOREST MANAGEMENT (IFM) IN NON-FEDERAL U.S. FORESTLANDS v2.0." ACR 2.0 (July).

———. 2023a. "Improved Forest Management (IFM) Primer," March.

———. 2023b. "The ACR Standard v8.0" v8.0 (July). https://acrcarbon.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/ACR-Standard-v8.0.pdf.

———. 2024. "REVERSAL RISK ANALYSIS AND BUFFER POOL CONTRIBUTION DETERMINATION v2.0" v2.0 (November). https://acrcarbon.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/ACR-Risk-Tool-v2.0-2024-11-19.pdf.

———. 2025. "ACR Tool for Risk Analysis and Buffer Determination V1.0." https://acrcarbon.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/ACR-Risk-Tool-v1.0.pdf.

Arbeláez-Cortés, Enrique. 2013. "Knowledge of Colombian Biodiversity: Published and Indexed." Biodiversity and Conservation 22 (12): 2875–2906. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-013-0560-y.

Asia Society. 2022. "Economic Displacement." July 25, 2022. https://asiasociety.org/policy-institute/navigating-belt-road-initiative-toolkit/glossary/social/economic-displacement.

Asian Development Bank (ADB). 2012. Gender Tool Kit: Energy : Going beyond the Meter. Manila: Asian Development Bank.

———. 2013. Gender Toolkit: Transport : Maximizing the Benefits of Improved Mobility for All. Mandaluyong City, Metro Manila, Philippines: Asian Development Bank.

———. 2024. Environmental and Social Framework. Asian Development Bank. https://www.adb.org/documents/environmental-social-framework.

———.2013. Tool Kit on Gender Equality Results and Indicators. Asian Development Bank. https://www.adb.org/documents/tool-kit-gender-equality-results-and-indicators.

Avery, Thomas Eugene, Harold E. Burkhart, and Bronson P. Bullock. 2019. Forest Measurements. Sixth edition. Long Grove, Illinois: Waveland Press, Inc.

B Corporation. 2025a. "B Corp Company Directory." Bcorporation.Net. 2025. https://www.bcorporation.net//en-us/find-a-b-corp/.

———. 2025b. "SDG Action Manager Tool." 2025. https://www.bcorporation.net//en-us/programs-and-tools/sdg-action-manager/.

———. n.d.-a. "B Impact Assessment." Accessed June 4, 2025. https://www.bcorporation.net//en-us/programs-and-tools/b-impact-assessment/.

———. n.d.-b. "Collective Action Initiatives from B Lab and Partners." Accessed June 4, 2025. https://www.bcorporation.net//en-us/programs-and-tools/collective-action/.

BeZero. 2022. "Carbon Accounting Template." BeZero Carbon. March 11, 2022. https://bezerocarbon.com/campaign/carbon-accounting-template.

Bloom Labs. 2021. "Bloom Labs: Biodiversity Credit Calculation Indicators & Metrics." Airtable. https://airtable.com/app8lx6rkX70v13EJ/shrvQcql5iO3M31PY/tbl3FSxPbwFzwXHrn/viw89cDVjmEdsk2Ng.

———. 2025. "Biodiversity Credit Metrics." Airtable. https://airtable.com/appYGQNrpZp58kHIk/shrr0TtB9RIkLqG9Y/tblYk3kiEovv4DlVP/viwwsmvznmiooiu2E.

Boomsma, Christine, Emma ter Mors, Corin Jack, Kevin Broecks, Corina Buzoianu, Diana M. Cismaru, Ruben Peuchen, et al. 2020. "Community Compensation in the Context of Carbon Capture and Storage: Current Debates and Practices." International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control 101 (October):103128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2020.103128.

Brill, Gregg, Deborah Carlin, Shannon McNeeley, and Delilah Griswold. 2022. "Stakeholder Engagement Guide for Nature-Based Solutions." Oakland, CA: United Nations CEO Water Mandate and Pacific Institute. https://pacinst.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/CEOWater_SEG_Final.pdf.

British Standards Institution (BSI). 2019a. Greenhouse Gases Specification with Guidance at the Organization Level for Quantification and Reporting of Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Removals. Under Review. BS EN ISO14064-1.

———. 2019b. Greenhouse Gases Specification with Guidance at the Organization Level for Quantification and Reporting of Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Removals. Under Review. BS EN ISO14064-2.

———. 2019c. Greenhouse Gases Specification with Guidance at the Organization Level for Quantification and Reporting of Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Removals. Under Review. BS EN ISO14064-3.

Carbon Credit Quality Initiative. 2022. "CCQI Methodology for Assessing the Quality of Carbon Credits v 3.0." https://carboncreditquality.org/download/Methodology/CCQI%20Methodology%20-%20Version%203.0.pdf.

Chandrasekharan Behr, Diji, Mairena Cunningham, Eileen, Kajembe, George, Mbeyale, Gimbage, Nsita, Steve, and Rosenbaum, Kenneth L. 2012. "Benefit Sharing in Practice : Insights for REDD+ Initiatives." License: CC BY 3.0 IGO. © World Bank. https://hdl.handle.net/10986/12619.

Chomba, Susan, Juliet Kariuki, Jens Friis Lund, and Fergus Sinclair. 2016. "Roots of Inequity: How the Implementation of REDD+ Reinforces Past Injustices." Land Use Policy 50 (January):202–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.09.021.

Convention on Biological Diversity Biosafety Unit. 2011. "Text of the Nagoya Protocol." Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. January 28, 2011. https://www.cbd.int/abs/text/articles?sec=abs-37.

"CORSIA." n.d. Climate Action Reserve (blog). Accessed June 2, 2025. https://climateactionreserve.org/corsia/.

Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund. 2025. "Biodiversity Hotspots Defined | CEPF." Cepf.Net. 2025. https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/hotspots-defined.

David Shoch and Erin Swails. 2024. "VM0042 Improved Agricultural Land Management v2.1." Verra Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) v2.1 (September).

David Shoch, Erin Swails, Edie Sonne Hall, Ethan Belair, Ben Rifkin, Bronson Griscom, and Greg Latta. 2022. "VM0045 IMPROVED FOREST MANAGEMENT METHODOLOGY USING DYNAMIC MATCHED BASELINES FROM NATIONAL FOREST INVENTORIES v1.0." Verra Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) v1.0 (October).

Dr. Igino Emmer, Dr. Brian Needelman, Stephen Emmett-Mattox, Dr. Stephen Crooks, Dr. Lisa Beers, Dr. Pat Megonigal, Doug Myers, Matthew Oreska, Dr. Karen McGlathery, and David Shoch. 2023. "VM0033 Methodology for Tidal Wetland and Seagrass Restoration v2.1." Verra Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) v2.1 (September).

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. 2024. "Environmental and Social Policy 2024." 2024. https://www.ebrd.com/home/news-and-events/publications/institutional-documents/environmental-and-social-policy-2024.html.

———.2019. "EBRD Performance Requirement 5 : Land Acquisition, Involuntary Resettlement and Economic Displacement." European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. https://bankwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/for-kvesheti-kobi-web.pdf.

European Commission. n.d. "Soil Erosion." World Atlas of Desertification. Accessed June 4, 2025. https://wad.jrc.ec.europa.eu/soilerosion.

European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE). 2016. "GENDER IMPACT ASSESSMENT: Gender Mainstreaming Toolkit." European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE). https://eige.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/eige_gender_impact_assessment_gender_mainstreaming_toolkit.pdf.

European Investment Bank (EIB). 2022a. "Environmental and Social Standards." European Investment Bank. https://www.eib.org/files/publications/eib_environmental_and_social_standards_en.pdf.

———. 2022b. European Investment Bank Environmental and Social Standards. European Investment Bank. https://www.eib.org/en/publications/eib-environmental-and-social-standards.

Fairtrade. 2019. "Standards for Small-Scale Producer Organisations v2.9." 09 2019. https://www.fairtrade.net/en/why-fairtrade/how-we-do-it/standards/who-we-have-standards-for/standards-for-small-scale-producer-organisations.html.

———. 2025a. "Fairtrade Standard for Hired Labour." Fairtrade.Net. 2025. https://www.fairtrade.net/en/why-fairtrade/how-we-do-it/standards/who-we-have-standards-for/hired-labour-standard.html.

———. 2025b. "Fairtrade Standard for Traders." 2025. https://www.fairtrade.net/en/why-fairtrade/how-we-do-it/standards/who-we-have-standards-for/trader-standard.html.

———. n.d. "Climate Standard." Accessed June 2, 2025. https://www.fairtrade.net/en/why-fairtrade/how-we-do-it/standards/who-we-have-standards-for/climate-standard.html.

FAO. 2017. "B7 Sustainable Soil and Land Management for CSA | Climate Smart Agriculture Sourcebook." Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. https://www.fao.org/climate-smart-agriculture-sourcebook/production-resources/module-b7-soil/b7-overview/en/.

Forest Stewardship Council. 2023. "FSC® PRINCIPLES AND CRITERIA FOR FOREST STEWARDSHIP." FSC-STD-01-001 V5-3 EN. FSC. https://open.fsc.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/0e2f50a2-bb15-4697-aa39-42d878506bbd/content.

Frontier. 2024. "Request for Offtake Proposals." https://frontierclimate.com/assets/offtake-rfp.pdf.

General Assembly resolution 2200A. 1966. "International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights." OHCHR. December 16, 1966. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-economic-social-and-cultural-rights.

———. 1996. "International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights." OHCHR. December 16, 1996. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-civil-and-political-rights.

Global Forest Watch. 2019a. "Erosion | Global Forest Watch Open Data Portal." April 2, 2019. https://data.globalforestwatch.org/documents/1542ee555fab419da25cd89b71d044b9/about.

———. 2019b. "Erosion - Overview." April 2, 2019. https://www.arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=1542ee555fab419da25cd89b71d044b9.

Gold Standard. 2016. "Gold Standard Methodology for Accreditation of Water Benefit Certificates V1.0." https://globalgoals.goldstandard.org/standards/PRE-GS4GG-Water/gs_wash_water_acess_methodology_v1_0.pdf.

———. 2022. "SIMPLIFIED METHODOLOGY FOR CLEAN AND EFFICIENT COOKSTOVES v3.0." Gold Standard for the Global Goals v3.0 (August).

———. 2023. "Gold Standard Safeguarding Principles and Requirements V 2.0." https://globalgoals.goldstandard.org/standards/103_V2.0_PAR_Safeguarding-Principles-Requirements.pdf.

———. 2024. "Programme of Activity Requirements and Procedures." Gold Standard for the Global Goals (blog). December 11, 2024. https://globalgoals.goldstandard.org/107-par-programme-of-activity-requirements/.

Green Climate Fund. 2019. "Operational Guidelines: Indigenous Peoples Policy." Text. Green Climate Fund. Green Climate Fund. August 31, 2019. https://www.greenclimate.fund/document/operational-guidelines-indigenous-peoples-policy.

———. 2023. "Environmental and Social Safeguards." Text. Green Climate Fund. Green Climate Fund. June 27, 2023. https://www.greenclimate.fund/projects/sustainability-inclusion/ess.

———. 2024. "Environmental and Social Safeguards (ESS) Report for FP164: Green Growth Equity Fund - 240 TPD Paddy Straw- 20 TPD CBG Plant of Sangrur RNG Pvt. Ltd., Unit at – Dhuri | Green Climate Fund." December 23, 2024. https://www.greenclimate.fund/document/environmental-and-social-safeguards-ess-report-fp164-green-growth-equity-fund-240-tpd-paddy.

———. 2025a. "Environmental and Social Safeguards (ESS) Report for FP106: Embedded Generation Investment Programme (EGIP) - Western Cape Wind Energy Facility (WEF)." April 23, 2025. https://www.greenclimate.fund/document/environmental-and-social-safeguards-ess-report-fp106-1.

———. 2025b. "Environmental and Social Safeguards (ESS) Report for FP198: CATALI.5°T Initiative: Concerted Action To Accelerate Local I.5° Technologies – Latin America and West Africa - CEGEDI – New Plastic Recycling Unit." Text. Green Climate Fund. Green Climate Fund. May 12, 2025. https://www.greenclimate.fund/document/environmental-and-social-safeguards-ess-report-fp198-4.

———. 2025c. "Environmental and Social Safeguards (ESS) Report for FP206/1: Resilient Homestead and Livelihood Support to the Vulnerable Coastal People of Bangladesh (RHL)." Greenclimate.Fund. March 1, 2025. https://www.greenclimate.fund/document/environmental-and-social-safeguards-ess-report-fp206-1.

———. 2025d. "Policies: Country Ownership." Text. Green Climate Fund. Green Climate Fund. March 18, 2025. https://www.greenclimate.fund/about/policies/country-ownership.

Group on Earth Observations Biodiversity Observation Network (GEO BON). n.d. "What Are EBVs?" GEO BON (blog). Accessed June 6, 2025. https://geobon.org/ebvs/what-are-ebvs/.

Haya, Barbara K., Samuel Evans, Letty Brown, Jacob Bukoski, Van Butsic, Bodie Cabiyo, Rory Jacobson, Amber Kerr, Matthew Potts, and Daniel L. Sanchez. 2023. "Comprehensive Review of Carbon Quantification by Improved Forest Management Offset Protocols." Frontiers in Forests and Global Change 6 (March). https://doi.org/10.3389/ffgc.2023.958879.

iNaturalist. n.d. "Observations · iNaturalist." Accessed June 4, 2025. https://www.inaturalist.org/observations?place_id=any&user_id=savimbo&verifiable=any.

Inter American Development Bank (IADB). 2021. "Marco de Política Ambiental y Social." IADB. https://www.iadb.org/es/quienes-somos/topicos/soluciones-ambientales-y-sociales/marco-de-politica-ambiental-y-social.

Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. 2018. "The Ripple Effect: Economic Impacts of Internal Displacement." https://doi.org/10.1163/2210-7975_HRD-9806-20180010.

International Center for Appropriate and Sustainable Technology (ICAST). 2025. "Carbon Credit Project - ICAST." Icastusa.Org. 2025. https://www.icastusa.org/services/carboncreditproject/.

International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). 2019. "CORSIA Emissions Unit Eligibility Criteria." https://www.icao.int/environmental-protection/CORSIA/Documents/ICAO_Document_09.pdf.

———. 2025. "Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA)." 2025. https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiZTZhNjIxZTAtMTk0NC00MjM4LWI4ZTAtYTcyYjA2ZWVhNWY5IiwidCI6ImU2MDkzNjQyLWZiNjMtNDhiYi04NjgzLWQxZDVkYTJhMTJlYSIsImMiOjN9.

International Finance Corporation (IFC). 2012. "IFC's Performance Standards on Environmental and Social Sustainability." Text/HTML. IFC. 2012. https://www.ifc.org/en/insights-reports/2012/ifc-performance-standards.

International Labour Organization (ILO). 1930. "Convention C029 - Forced Labour Convention, 1930 (No. 29)." 1930. https://normlex.ilo.org/dyn/nrmlx_en/f?p=1000:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C029.

———. 1989. "Convention 169 - Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989 (No. 169)." International Labour Organization (ILO). https://normlex.ilo.org/dyn/nrmlx_en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:55:0::NO::P55_TYPE%2CP55_LANG%2CP55_DOCUMENT%2CP55_NODE:REV%2Cen%2CC169%2C%2FDocument.

———. 1999a. "Convention C182 - Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, 1999 (No. 182)." 1999. https://normlex.ilo.org/dyn/nrmlx_en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C182.

———. 1999b. "Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention."

———. 2006. "Convention C187 - Promotional Framework for Occupational Safety and Health Convention, 2006 (No. 187)." 2006. https://normlex.ilo.org/dyn/nrmlx_en/f?p=normlexpub:12100:0::no:12100:p12100_instrument_id:312332:no.

———. 2016. "What Are Part-Time and on-Call Work?" November 11, 2016. https://www.ilo.org/resource/other/what-are-part-time-and-call-work.

———. 2024a. "ILO Conventions on Child Labour | International Labour Organization." January 28, 2024. https://www.ilo.org/international-programme-elimination-child-labour-ipec/what-child-labour/ilo-conventions-child-labour.

———. 2024b. "ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work." Ilo.Org. January 28, 2024. https://www.ilo.org/about-ilo/mission-and-impact-ilo/ilo-declaration-fundamental-principles-and-rights-work.

———. 2025. "The Occupational Safety and Health Convention (No. 155): A Fundamental Convention." March 3, 2025. https://www.ilo.org/resource/other/occupational-safety-and-health-convention-no-155-fundamental-convention.

International Social and Environmental Accreditation and Labelling Alliance (ISEAL). 2021. "ISEAL Credibility Principles." 2021. https://isealalliance.org/what-we-do/credible-practice/iseal-credibility-principles.

———. 2023. "ISEAL Codes of Good Practice." 2023. https://isealalliance.org/what-we-do/credible-practice/iseal-code-good-practice-sustainability-systems.