Reality Check: The United States Has the Only Major Power Grid without a Plan

Inter-regional planning and transmission could help keep the lights on during extreme weather.

The Myth

The US electric grid is often referred to as the greatest machine in the world. It is indeed an engineering marvel: a network of several hundred thousand miles of power lines connect thousands of electric generators to power households and businesses across the contiguous United States. But in the aftermath of winter storm Elliott and the rolling power outages its frigid cold inflicted on many Americans, we need to ask ourselves: is this machine a match for these types of extreme weather events blanketing the country with ever increasing frequency and ferocity?

The Reality

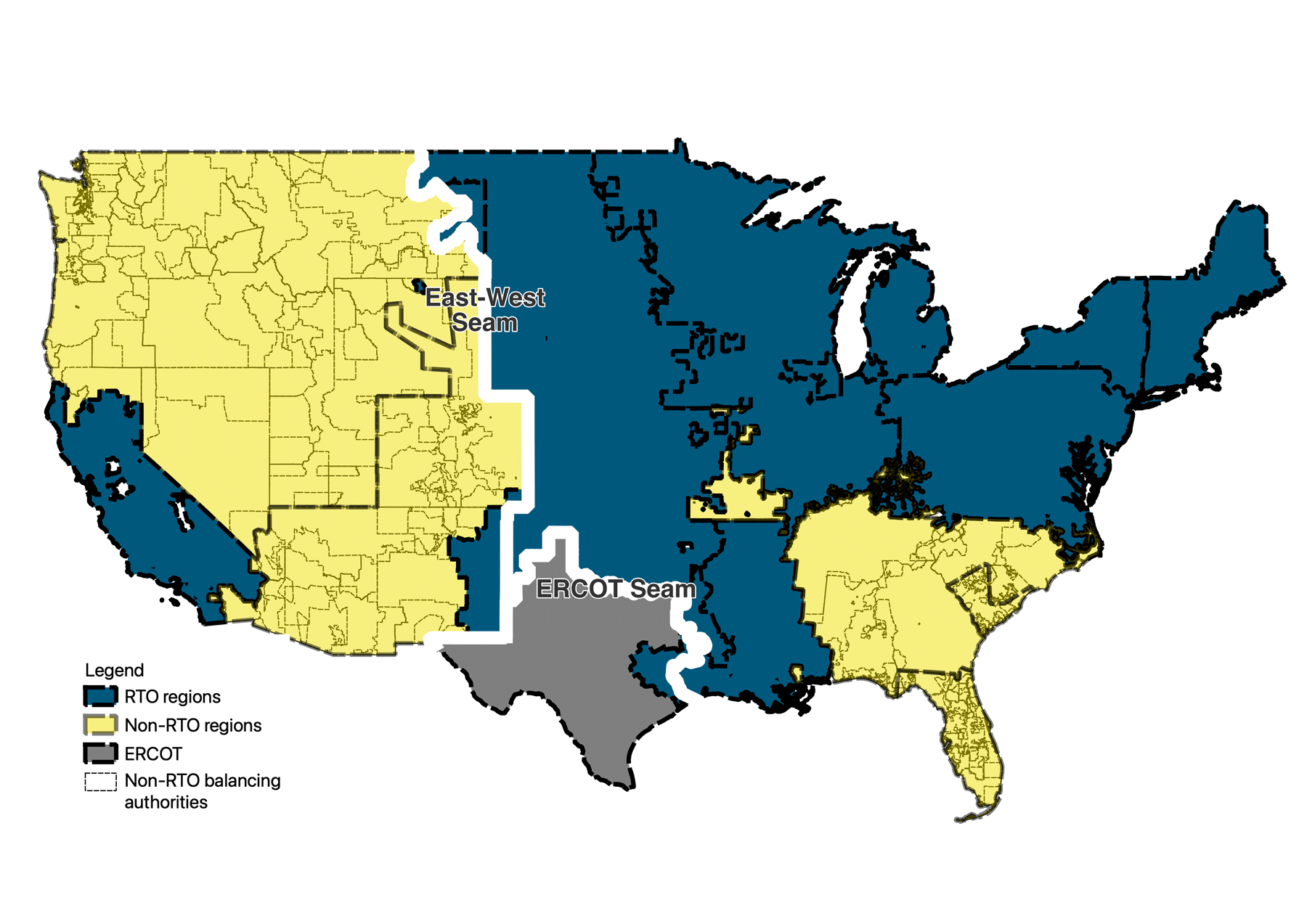

The US power grid is, in fact, highly fragmented and consists of not one, but three different sections. These are called the Eastern, Western, and ERCOT interconnections — three separate power grids that are almost completely isolated from one another, electrically speaking. To make matters worse, the high-voltage, long-distance electric transmission lines that form the backbone of each of these grids are largely planned in even greater local isolation.

Today, there are 12 different transmission planning regions, all of which except for the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) are under the jurisdiction of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). Yet, only six of them are full Regional Transmission Organizations (RTOs) — sometimes referred to as Independent System Operators, a nuanced distinction and yet another acronym that we shall spare the readers from — with the mandate and authority to conduct transmission planning for their region. The remaining five planning regions in the West and Southeast are much more loose associations of dozens of vertically integrated utilities, which tend to plan transmission mostly with just their own local territories (or balancing authorities) in mind.

Illustration of major planning boundaries within the US power grid

As Aaron Bloom, Executive Director of NextEra Energy Transmission, LLC put it at a recent FERC workshop on the matter, “The United States is the only macro grid in the world that doesn’t have a plan of any type.” Indeed, both the European Union and China have continental-/national-scale grid development plans. The United States does not.

The Problem with Fragmented Planning

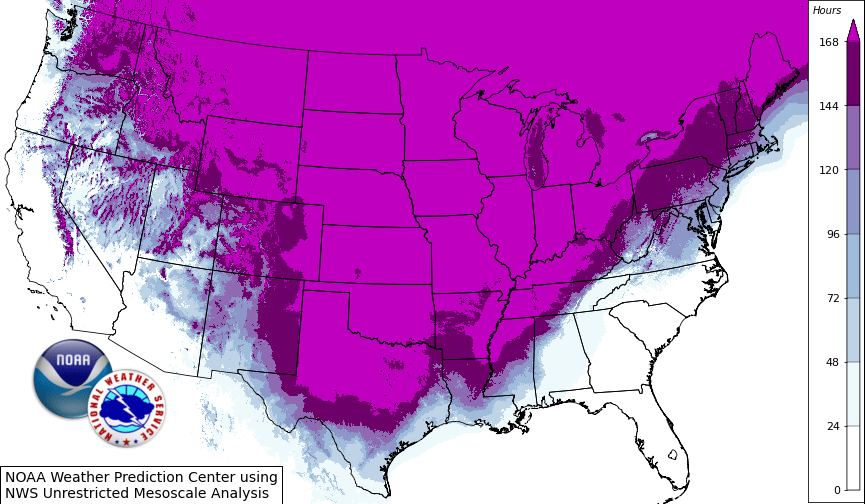

This type of fragmented planning framework is highly problematic, because the power grid is under growing stress from climate change-related extreme weather. High-stress events like winter Storm Elliot — the extreme cold snap that blitzed much of the nation at the end of last year — or Winter storm Uri in 2021, which led to over 210 deaths, caused almost 70 percent of Texans to lose power and 50 percent to lose water, and cost at least $80 billion, are becoming increasingly frequent. The associated weather patterns are much larger than our current fragmented grids and grid planning regions, which therefore struggle with the coordinated response needed to future-proof our vital power supply system.

Number of hours below freezing during Winter Storm Uri (Feb 12-19, 2021)

Luckily, FERC is Working on Solutions

Last year, FERC issued a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NOPR) that, if adopted, will go a long way in fixing many of the hurdles that plague planners within the 11 FERC transmission planning regions. However, the Commission has yet to take similarly strong action to fix planning between those regions. As a first important step, FERC convened a host of experts on December 5 and 6, 2022 to discuss how it can help improve this type of inter-regional planning.

In that workshop, researchers, industry leaders, regulators, advocates, and other experts discussed key regulatory and technical questions related to how FERC can best spur additional beneficial “inter-regional transfer capability” — the ability to move power between regions. Importantly, there was near-unanimous consensus among the diverse group of experts that increasing today’s limited capabilities to transfer power between regions would bring multiple massive benefits for the US power grid and its customers. From more efficient power plant operation on normal days to ensuring the lights will stay on even during the most challenging periods, inter-regional transfer capability means that neighbors can efficiently share resources and help each other out in a pinch. However, several key questions remain, three of which are summarized below.

Three Questions on Inter-Regional Transmission

First, FERC was asking whether it should mandate a minimum amount of power transfer capability between regions, or if it should require a planning process for neighboring regions to figure out the right transfer capability between them for themselves. Rob Gramlich, founder and president of Grid Strategies, advocated for a hybrid approach. This would include both a minimum floor set by FERC and provide for a robust inter-regional planning process, through which neighboring regions would jointly identify additional beneficial inter-regional transmission solutions. Others added that harmonized regional planning standards set by FERC are also desperately needed to facilitate joint planning between willing regions on an equal footing.

Second, the panelists debated whether FERC should set a minimum requirement based on a simple metric. The EU for instance simply asks its member states to enable at least 15 percent of installed electricity production capacity to be deliverable to their neighbors by 2030. However, some panelists argued that complex modeling, potentially involving supercomputers, was needed to robustly quantify all the diverse benefits of improved inter-regional connectivity. Others pointed out that the reliance on simplified metrics, such as the common 1 day in 10 years loss of load expectation standard used for resource adequacy modeling, has long been an established practice in power system planning.

Last, and certainly not least, there was of course debate of the old question “who pays” for the new power lines. It is an established FERC principle, affirmed by the courts, that costs should be allocated at least roughly commensurate with the benefits received. Exactly how rough that cost/benefit calculation may be is however often subject to fierce debate. Furthermore, the cost allocation question here is closely connected to the modeling debate: how precise can and should the expected benefits of new inter-regional links be calculated to allow for a fair and at least roughly commensurate cost allocation?

A Path Forward

During the FERC workshop, Dr. Dev Millstein from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, highlighted both the difficulty and importance of forecasting rare but extreme events such as Winter Storm Uri. This is because the ability to transfer power between distant regions yields not only economic benefits on normal days, but also comes with a potentially enormous insurance value for emergency situations. According to a report from Grid Strategies and ACORE, one additional gigawatt (about one large transmission line) between ERCOT and the Southeastern US could have saved nearly $1 billion during winter storm Uri, while keeping the heat on for hundreds of thousands of Texans. Another report from the Energy Systems Integration Group shows inter-regional transmission yields multiple diverse benefits — from production and capital cost as well as emission savings, to resource adequacy and resilience benefits.

Therefore, FERC should require both a minimum amount of inter-regional transfer capability and a robust inter-regional planning process. Recognizing the potentially life-saving insurance value of additional inter-regional transfer capability, the minimum requirement should be based on a robust yet simple and readily actionable metric. The increasingly urgent need to protect consumers from future disasters means that the cost allocation question needs to be resolved quickly. This would likely be best achieved by applying the same simple and broad cost socialization as with any other public good.

However, FERC should not stop there. It should also mandate a robust inter-regional transmission planning process. This process should rely on forward-looking, multi-value, and scenario-based modeling to ensure regional planners identify and seize the multiple additional benefits of inter-regional transmission beyond a minimum requirement — and fairly allocate the associated costs commensurately. Because if the lights stay on when the storm hits, everyone wins.