A.B. Lovins, D. Ürge-Vorsatz, L. Mundaca, D.M. Kammen, & J.W. Glassman, “Recalibrating Climate Prospects,” Envir. Res. Lett. 14 120201, doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ab55ab. Reposted under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 license.

A bracing antidote to the “doomism” lately fashionable among both climate activists and skeptics was released Monday 02 December 2019 at https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab55ab, which points to the publisher’s (Institute of Physics) website: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/ab55ab.

This major peer-reviewed scientific paper concurs that the global climate emergency requires strong, broad, and rapid action. (An important summary of “tipping points,” confirming that a 2C˚ target is too high, was published four days ago in Nature 575, 592-595 (27 Nov 2019), https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-03595-0.) Yet powerful tools to mitigate climate change offer far more effective solutions, sooner, at lower cost, than are included in nearly all models that now guide climate policy. Policymakers can’t make choices they don’t know they have, so this modeling gap diverts policy attention and investment to slower, harder, costlier options that buy less and later mitigation, increasing risks. The climate challenge is tough enough without policymakers being hobbled, private firms diverted, and citizens discouraged by limiting their horizons. This new paper therefore seeks to expand those horizons and soberly rebalance the climate conversation, paying as much attention to opportunity as to urgency, so resources can be better focused on closing the dangerous gap between potential mitigation and actual adoption before it is too late.

The paper’s core message is this: With few and recent exceptions, the “Integrated Assessment Models” that convert climate science into consequences and choices have understated what we can do to reverse climate change by at least as much as the conservative scientific models have understated its speed and runaway potential. Offsetting these two biases, what Jeremy Grantham calls “the race of our lives”—and many see as the race for our lives—is very much on. Despair and complacency are equally unwarranted; it is time to keep calm and carry on. The outcome depends on our spirit and mood (people cannot be depressed into action), our ability to see the full menu of choices, and our effectiveness in choosing and executing those most fit for purpose.

Nearly all the models that currently shape policy choices underscope modern energy solutions. They:

- severely understate what efficient energy use can do: it delivered three-fourths of the global economy’s decarbonization in 2010–16, but can do far more—especially now that new design methods can make buildings, vehicles, equipment, and factories severalfold more efficient than had been thought, and at lower cost (https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/aad965);

- systematically understate how quickly, fully, reliably, and profitably modern renewable energy supplies can replace fossil fuels;

- overlook the potential for efficiency and renewables to exploit increasing returns caused by positive feedbacks analogous to those that are a threat in climate change;

- focus only on technologies and devices rather than on whole systems, and on microeconomics rather than complex social processes; and, combining these opportunities,

- downplay how efficiency and renewables together can not just augment but displace fossil fuels—often at a profit—and free up enormous amounts of investment to fund other needs.

The best model avoiding these flaws found in mid-2018 (https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-018-0172-6) that efficiency-centric strategies could robustly achieve the Paris Agreement’s aspirational 1.5˚C goal and the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, cut 2050 supply costs by more than a trillion dollars per year, and require no carbon removal except by natural systems. Detailed and rigorous assessments of the world’s top carbon-emitting economies—China and the United States—reached similar conclusions, reported in the peer-reviewed energy literature but overlooked in the climate modeling literature.

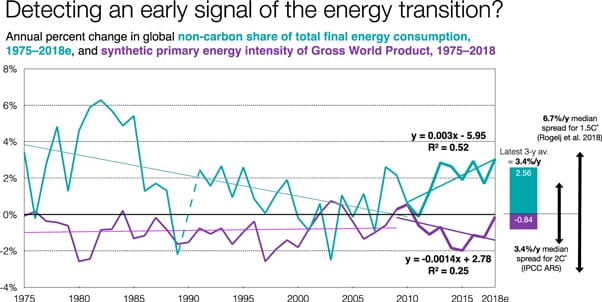

To be sure, the world’s CO2 emissions, having stabilized during 2014–16, then resumed rising as energy savings distressingly slowed in each of the past three years, to a torpid rate that in 2018 was nearly as slow as the 1981–2010 average. But many outdated models assume the dismal pre-2010 performance must constrain the future. In fact, since about 2010 energy savings have sped up by nearly a percentage point per year on average, carbon-free energy supply growth greatly accelerated, and both together have sustained the strongest decarbonization in three decades. (Please see the graph below; being expressed as share, not absolute value, it doesn’t reflect the 2.4-fold growth in world energy use during 1975–2018.)

During and despite the past three years’ savings slowdown, carbon-free supply growth averaged three times as important, slightly more than offsetting the lost savings in 2016 and 2018 while moderating their harm in 2017. With early signals for 2019 pointing to improvement in both savings and renewables, understanding their full potential can help double their average 2015–18 combined pace (3.4%/y) to a level that, if sustained to 2050, could achieve 1.5C˚. Better models can support that speedup, but we needn’t wait to get started on this high-ambition agenda.

The paper’s wide-ranging evidence will surprise many climate policy experts. It also contains two technical surprises:

- Current models and many statistical datasets omit a category of renewable energy supply (“modern renewable heat” from biomass, solar, and geothermal) roughly as big as wind and solar power combined. In 2018 this source delivered more than 4% of the world’s final energy consumption and raised its 2018 carbon-free share from 24.3% to ~28.5%, so the world’s carbon-free total energy share is larger than models assume, by the equivalent of ~3.5 years of recent carbon-free growth.

- Any one or more hydrocarbon firms could attempt a competitive rollup of the global business opportunity to abate deliberate methane releases from flares and engineered vents in upstream oil and gas operations. This novel notion—looking at all firms’ assets, not just one’s own, and shifting from compliance to entrepreneurial mentality—holds promise of rapidly and profitably turning down the global thermostat, buying time to abate CO2 emissions. It’s like discovering a hidden handbrake on the runaway carbon train: it can’t stop the train, but could usefully slow it down.

The paper’s balanced critique of most current Integrated Assessment Models, and its suggestions for improving them, may stimulate much discussion among modelers. For the broader audience of practitioners in many disciplines and pursuits, its insights into the richness of the new toolkit for abating climate change—through design, technology, policy, finance, marketing and delivery methods, new business models, behavioral science, urban form, societal values and engagement—will surprise, gratify, and empower many to do more and better. Add ambition and stir vigorously.

* * *

“Recalibrating Climate Prospects” (17 pages plus online Supplemental Materials in Word and Excel), Environmental Research Letters 14 (2019) 120201, 02 December 2019, open access, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab55ab. The five coauthors are:

- Dr. h.c. mult. Amory B. Lovins, Cofounder and Chairman Emeritus, Rocky Mountain Institute, Basalt, Colorado, USA (corresponding author)

- Dr. Diana Ürge-Vorsatz, Professor of Environmental Sciences and Policy, Central European University, Budapest, Hungary; Vice Chair, IPCC Working Group III

- Dr. Luis Mundaca, Professor, International Institute for Industrial Environmental Economics, Lund University, Sweden; Lead Author, IPCC AR5 WG3 and 2018 1.5˚C Special Report

- Dr. Daniel M. Kammen, Professor and Chair of Energy and Resources Group, Director of Center for Environmental Public Policy, Goldman School of Public Policy, and Professor of Nuclear Engineering, University of California at Berkeley; Contributing or Coordinating Lead Author on various IPCC publications, 1999–

- Mr. Jacob W. Goldman, Schneider Fellow, Rocky Mountain Institute, Basalt, Colorado, USA