Green Fertilizer Markets and Innovation

The evolution of the modern fertilizer industry and the current fertilizer market in the United States.

Introduction

Fertilizer is one of the pillars of modern agriculture. Although synthetic fertilizers unlocked exceptional yields, they have a significant climate impact. 84% of production emissions come from ammonia synthesis, which typically runs on natural gas.

This report describes how the modern fertilizer industry evolved and presents the current fertilizer market in the United States. Today, the United States consumes 11% of the world’s synthetic nitrogen. Conventional Haber-Bosch production technology, powered by natural gas, remains the main pathway to synthesize ammonia — a widely used fertilizer and the starting material for all synthetic nitrogen fertilizers. However, several alternative solutions offering lower carbon footprint and higher energy efficiency are emerging. This report provides an overview of these opportunities.

Moreover, this work also provides an overview of the most popular ammonia-derived nitrogen fertilizers, highlighting their key benefits and potential drawbacks. Being suitable for different application cases, these fertilizers allow for higher application efficiency and lower emissions. In this way, green ammonia opens up a wide range of low-carbon nitrogen fertilizers.

Discussions with original equipment manufacturers (OEMs), financial institutions, and project developers allowed us to formulate key barriers to the development of green ammonia projects and the adoption of new technologies. The report concludes with an overview of state incentives that support fertilizer market advancement.

The Role of Fertilizers in Agriculture

Fertilizers are a core element of modern agriculture, helping support the nutritional needs of half of the world’s population. Nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K) are the major nutrients required by plants for optimal growth, and thus these three elements are manufactured into fertilizers. Sufficient fertilization of crops not only allows for higher yields but also lowers water and land consumption of farming.

Fertilizer application and emissions

While the importance of fertilizers is undisputed, the fertilizer industry is one of the highest emitting sectors of the global economy. Fertilizers are responsible for 1.31 Gt of annual CO2e emissions, which is greater than the combined carbon footprint of aviation and shipping industries.[1] Of this estimated total, 483 megatons (Mt) are generated during production and 829 Mt during application of fertilizers, of which 627 Mt come from direct and indirect N2O emissions, and 202 Mt come from CO2 emissions. This is consistent with the analysis conducted by the International Fertilizer Association (IFA), according to which around 20%–50% of emissions originate from production, while 50%–80% are generated during the application phase.[2]

Emissions generated during fertilizer application are both hard to measure and contingent on several external factors which cannot be controlled by farmers, like weather conditions and soil properties. Nevertheless, this doesn’t mean that these emissions cannot be mitigated. According to IFA’s analysis, significant reductions in emissions from fertilizer use can be achieved through improved nitrogen use management, optimization of agricultural inputs, expanded application of nitrification and urease inhibitors, changes in crop rotation, and land sparing practices. The measures considered are highly dependent on local conditions and will have different efficiencies in different environments. In addition, because farmers operate as part of a large food industry, they have limited leverage to incorporate changes in their established practices, so deep interventions require a complex approach and broader engagement across the value chain.

The development of NPK fertilizer

While nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium are collectively referred to as NPK, each macronutrient has a distinct role in agriculture. And although the industrial production of potash, a trade name for potassium bearing minerals used for fertilizer, and phosphate, a salt form of phosphorus, started in the middle of the 19th century, the role of nitrogen was not yet evident and thus the first nitrogen fertilizers emerged much later.

Industrial production of phosphate fertilizers started in 1840. Novel chemical methods of phosphate rock treatment allowed for industrial superphosphate production and led to construction of tens of fertilizer factories around the globe by the end of the century. Potash production was limited by the feedstock availability, and salt deposits discovered in Germany in 1860 became the first large-scale source of potash in the world. Germany emerged as a global leader of potash production and held this position until the 20th century when significant potash deposits were found in other regions of the world.

Elements of the nitrogen cycle were discovered in stages during the 19th century. As nitrogen availability in soil and its uptake mechanisms were recognized, demand for nitrogen fertilizers started surging. Three industrial-scale nitrogen fertilizer production methods were developed by the early 1900s – calcium nitrate production through an electric arc process, calcium cyanamide production using an electric furnace, and ammonia synthesis using a Haber-Bosch process, the last of which ultimately became the main production pathway. Today, more nitrogen is consumed in the United States than potassium and phosphorus combined, dominating the fertilizer market.

Exhibit 1. US fertilizer consumption (1961-2021) [3]

The US fertilizer market — beginnings

The fertilizer industry developed together with agriculture. In the beginning of the 20th century, extensive agriculture was still a feasible approach for US farmers, where limited resources (e.g., labor, machinery, fertilizers) were compensated by extending the cultivated land. However, as land fertility gradually dropped, farmers moved to new lands, making arable land a scarce resource. Intensive agriculture then became the only viable option, where higher yields were reached through increased inputs and fertilizers started to play a significant role.

As the fertilizer industry scaled up, the market landscape started changing for small players. Centralization of the market had begun, and small-scale local fertilizer mixers could not compete with large-scale bulk producers. Fertilizer production technologies continued to evolve and production facilities began scaling up and becoming more energy efficient, contributing to a decrease in fertilizer prices. Over time, compound fertilizers incorporating all three macronutrients (NPK) became common.

A series of mechanical and infrastructural innovations was also introduced, facilitating efficient farming. At the same time, novel varieties of cereal crops were developed starting in the 1930s, offering a better response to fertilizers, higher resistance to drought, and shorter maturing time. As a result of these factors and significant funding allocated to agricultural research and development, an agricultural productivity surge in the United States started in the 1930s. By 2007 land productivity increased by 300%.

Exhibit 2. US agricultural productivity (1910-2007)

The US fertilizer market — today

Ammonia contains 82% nitrogen by weight, and because it is so nitrogen-rich, it has been used as the primary building block for nearly all synthetic nitrogen fertilizers used in agriculture. For economic reasons, ammonia plants are often built near other fertilizer facilities, producing urea, urea ammonium nitrate (UAN), or ammonium nitrate.[5] As ammonia production requires natural gas as the main feedstock, fertilizer facilities also require connection to gas infrastructure. As a result of these constraints, 60% of ammonia production in the United States is concentrated in Texas, Oklahoma, and Louisiana. Moreover, the US ammonia market is characterized by a high level of centralization, as the four largest producers cover 71% of national production capacity.[6]

Around 90% of nitrogen consumed from fertilizers are sourced from anhydrous ammonia, urea, and urea ammonium nitrate, which have almost equal market shares. It is important to note that the United States remains the leading market for direct ammonia application, while in other regions ammonia is mainly used for production of other fertilizers. At the same time, consumption of urea and UAN in the United States demonstrates an upward trend, while the application of ammonia is slightly decreasing.[7]

Exhibit 3. US consumption of ammonia-based (Nitrogen) fertilizers in kt/a (1973-2022)

Ammonia Technology Pathways

Given its crucial role in agriculture, the large-scale production of ammonia is essential to meeting global food demands, and so, ammonia is synthetically manufactured through industrial processes that convert atmospheric nitrogen into a usable form.

The Haber-Bosch (HB) process is the method by which hydrogen and nitrogen are converted into ammonia (NH₃) through the use of a high-pressure, high-temperature reactor and a chemical catalyst. Utilized in industry since the early 1900s, HB is already a mature technology. However, while nitrogen is sourced from the air, hydrogen is conventionally sourced from natural gas (methane, CH4) through a process called Steam-Methane Reforming (SMR), which releases significant amounts of carbon dioxide (CO₂) and accounts for over 1% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

The compounding challenges of carbon-intensive ammonia production process and the price volatility of natural gas have given rise to the need for alternative low-carbon pathways to produce ammonia. Fortunately, promising technological solutions to decarbonize ammonia production have emerged over the last several decades.

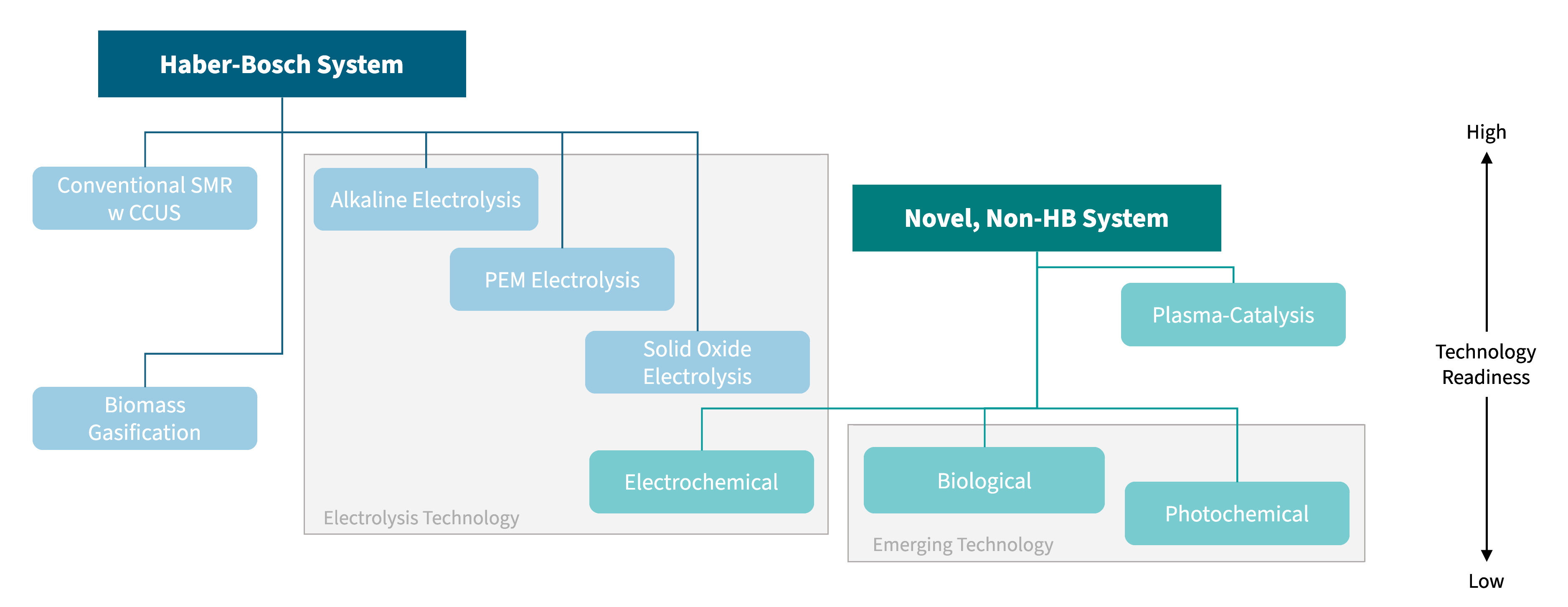

Ammonia production technologies generally fall under two categories: those that utilize the HB process, and those that are more novel. By capturing the carbon emitted or by sourcing hydrogen from other feedstocks like water (H2O), the ammonia production process can become much less carbon intensive.

Exhibit 4. Technology tree for low-carbon ammonia fertilizer production methods

Source: RMI

Promising low-carbon ammonia production pathways

1. Conventional Haber-Bosch with CCS, aka Blue Ammonia

Blue ammonia production captures and stores (or utilizes) the CO₂ emissions generated from natural gas-based hydrogen production. This approach combines the conventional SMR process with carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology and then utilizes the Haber-Bosch process to combine the “blue hydrogen” and nitrogen to create ammonia. Blue ammonia can significantly reduce emissions depending on the capture efficiency.

- Hydrogen Feedstock: Natural gas/methane (CH4)

- Key Technologies: Steam methane reforming (SMR) or autothermal reforming (ATR) to produce hydrogen from natural gas, coupled with CCS

- Advantages: Utilizes established infrastructure; CCS reduces CO₂ emissions

- Challenges: High cost and energy requirements for CCS; concerns about CO₂ leakage over time; requires access to geologic sites for CO2 sequestration

- Commercial Readiness: Commercial-scale SMR+CCS plants have been demonstrated around the world; over 20 ammonia facilities with CCS integration are under development

2. Biomass Gasification with CCS

Low-carbon hydrogen can be produced from biomass through the thermochemical process of gasification, where heat, pressure, and steam are used to convert materials directly into a gas without combustion. Then, adsorbers or special membranes can separate the hydrogen from this gas stream. Accompanied by carbon capture technology, biomass-based ammonia is considered to be one of the most sustainable methods of fertilizer production because it can utilize both agricultural and municipal waste. However, although this production pathway is technologically feasible, strong barriers prevent biomass ammonia development.

- Hydrogen Feedstock: Biomass

- Key Technologies: Gasification

- Advantages: Biomass is an abundant resource; CCS reduces CO₂ emissions

- Challenges: High capital costs; large variation in biomass feedstocks; limited sources of sustainable biomass; high biomass transportation costs; CCS concerns about leakage; requires access to geologic sites for CO2 sequestration

- Commercial Readiness: Biomass gasification is a mature technology, however, its viability for cost-competitive hydrogen and ammonia production will depend on the lowering of feedstock costs and the insights gained from commercial demonstrations. No biomass-to-ammonia projects are currently under development.

3. Electrolysis-Based Ammonia Production, aka Green Ammonia

Green ammonia is produced using renewable electricity (e.g., from wind or solar) to electrolyze water, producing hydrogen from water in a zero-carbon process. then combined with nitrogen to synthesize ammonia. Green ammonia is viewed as the most sustainable option, achieving near-zero emissions in production.

- Hydrogen Feedstock: Water (H2O)

- Key Technologies: Electrolysis (alkaline, PEM, or solid-oxide electrolysis), Haber-Bosch synthesis powered by renewable energy

- Advantages: No CO₂ emissions; uses abundant renewable resources; decoupling from natural gas pricing and supply chain risks; suitable for small-scale/localized ammonia fertilizer production

- Challenges: High cost of renewable hydrogen; flexible system design required for intermittent renewable energy supply may impact scalability and costs

- Commercial Readiness: Electrolysis technology is well developed and demonstrated in commercial environments; one fully renewable electrolysis-based ammonia facility deployed in the US

4. Electrochemical Ammonia

Electrochemical ammonia is a promising alternative to the Haber-Bosch process that can operate in a low-pressure environment. By running an electric current through an electrochemical cell containing a source of hydrogen and nitrogen, a single-step nitrogen reduction reaction (NRR) can occur.

- Hydrogen Feedstock: Water (H2O)

- Key Technologies: Electrochemical cell

- Advantages: No CO₂ emissions; low-pressure ammonia synthesis; single-step process simplicity; suitable for small-scale/localized ammonia fertilizer production

- Challenges: low ammonia synthesis performance results at the research level; high energy requirements; reactor catalyst optimization

- Commercial Readiness: Lab-scale prototyping phase

5. Plasma-Catalysis Ammonia

Plasma-based methods for nitrogen fertilizer production were developed in the early 20th century before the invention of the Haber-Bosch process, with thermal plasma technology first introduced in 1903. However, the high-temperature process was soon replaced by the more efficient and cost-effective Haber-Bosch process. More recently, non-thermal plasma (NTP) ammonia has emerged as a likely competitor to small-scale electrolysis systems, as it can be used for on-farm ammonia fertilizer production. The low-temperature and low-pressure plasma reactors can produce nitrogen-based fertilizers such as nitric acid and ammonia, and this method does not require the Haber-Bosch process.

- Hydrogen Feedstock: Water (H2O)

- Key Technologies: NTP reactor

- Advantages: No CO₂ emissions; low-pressure, low-temperature ammonia synthesis; suitable for small-scale/localized ammonia fertilizer production

- Challenges: low energy efficiency; reactor catalyst optimization

- Commercial Readiness: Emerging from lab-scale to pilot-scale project phase

6. Photochemical Ammonia

Photochemical ammonia production uses sunlight to convert nitrogen (N₂) from the air into ammonia (NH₃), without relying on high temperatures or pressures like the traditional Haber-Bosch process. The process uses special materials called photocatalysts to capture solar light and uses its energy to trigger chemical reactions, splitting water (H₂O) molecules into hydrogen (H) and oxygen (O) and then combining the hydrogen atoms with nitrogen from the air, forming ammonia (NH₃).

- Ammonia Feedstock: Nitrogen (N2), Water (H2O), and light

- Key Technologies: Photocatalysis

- Advantages: No CO₂ emissions; utilizes renewable energy

- Challenges: More research required to improve efficiency and stability of photocatalytic materials

- Commercial Readiness: Research studies have shown results with very low efficiencies, more research and testing are needed to validate this technology and while promising in lab settings, scaling up photochemical ammonia production for industrial use remains a major challenge.

7. Biological Ammonia

Biological ammonia fertilizers offer a natural alternative to synthetic nitrogen. Certain microbes are capable of using the nitrogenase enzyme to fix atmospheric nitrogen, which is inert, into reactive, biologically-available nitrogen in the form of ammonia. These bacteria, already present in nature, can be manufactured into a fertilizer product that can deliver nitrogen directly to the roots of crops.

- Feedstock: None

- Key Technologies: Gene editing

- Advantages: A non-synthetic fertilizer and thus can be used in organic agriculture; microbial fertilizers require much less energy to produce than synthetic fertilizers

- Challenges: More research required to validate efficacy; highly dependent on soil conditions

- Commercial Readiness: Several companies are undergoing lab tests and field trails to ensure their microbial products are safe and sustainable for various crops, some commercial products are available

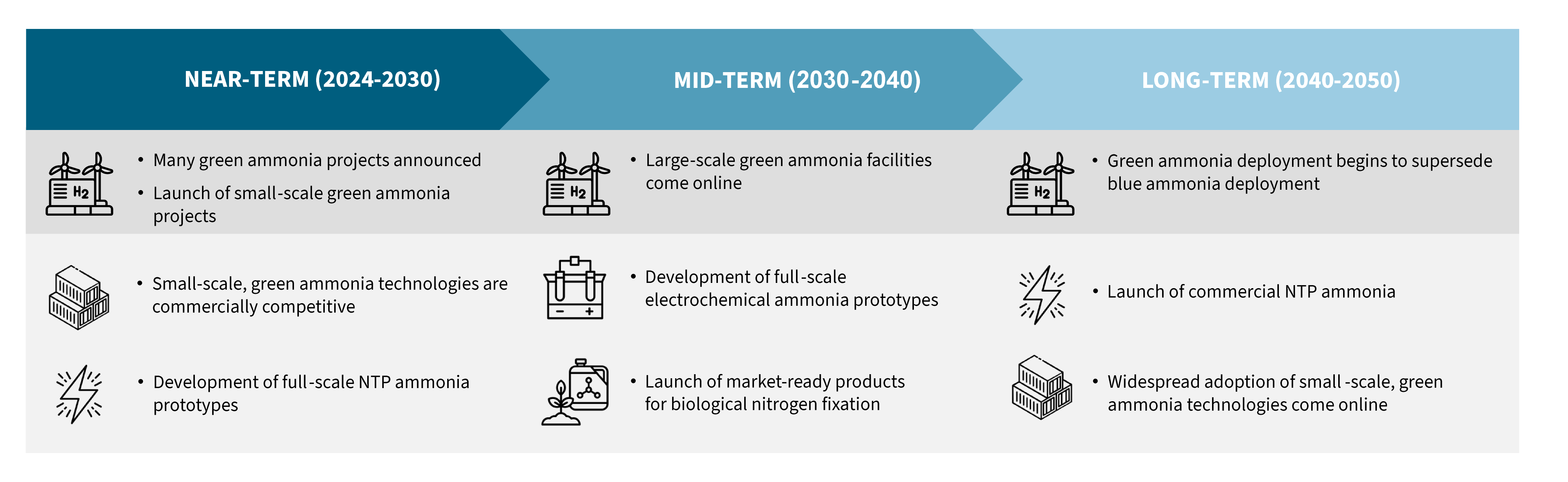

Within the next few decades, the convergence of renewable energy advancements, carbon capture improvements, and innovative reactor designs will create a portfolio of ammonia production technologies that not only meet the world’s fertilizer needs but also contribute to a low-carbon, sustainable future.

Exhibit 5. Projected deployment milestones for various low-carbon ammonia fertilizer technologies

Source: RMI

Ammonia Derived, Nitrogen Fertilizers

While nitrogen makes up 78 percent of the air, most crops can only utilize nitrogen through their roots after it has been converted into the nitrate form. In fact, this nitrogen conversion, called “nitrification”, is a multi-step chemical process that is highly sensitive to soil properties, moisture, and temperature. Various fertilizers offer different ways of delivering nitrogen to plants. Nitrate fertilizers offer a quick way, allowing to skip the nitrification process altogether. Nitrogen fertilizers differ not only in the amount of nitrogen they contain, but also in the rate of nitrogen release, potential losses and effects on soil quality, application methods, and transportation and storage infrastructure required.

After fertilizers are applied, they are subject to volatilization losses, which means that some of the ammonia they contain is lost to the atmosphere in a gaseous form. The amount of these losses depends on the fertilizer type, but also on application conditions, like soil acidity, moisture, and temperature. Then the nitrification process itself also develops with losses that occur at different stages. Because nitrate fertilizers do not require nitrification, they are not exposed to the losses that occur during that process and therefore the amount of nitrate available in the soil can be better estimated. As a result, the nitrogen fertilization process can be managed more efficiently and have a smaller impact on the environment. However, added nitrates or those formed during the nitrification process can also be lost. Nitrates are characterized by high mobility in the soil. Excessive soil moisture, such as from heavy rainfall, can lead to leaching nitrates deep into the soil. There, nitrates can deteriorate the quality of ground waters, and in large amounts can even make water toxic to humans.

Besides environmental damage, all nitrogen loss means less nitrogen for crops and lower yields. As a result, several countries have either already implemented or are in the process of developing regulations for more efficient fertilization. Often, these regulations are designed to facilitate adoption of inhibitors, chemical additives that can slow the conversion of fertilizer to the nitrate form. This way total nitrogen uptake by plants is increased, while nitrogen losses are minimized. As urea is the most popular fertilizer in the world and is also subject to the highest volatilization losses, many policy instruments are specifically targeting urea and application of urease inhibitors. Although these inhibitors have already demonstrated high efficiency in improving yields, their application means additional expenditures for farmers. Incentive programs can be an efficient instrument to facilitate their adoption. In 2015 Indian government mandated that all subsidized urea be coated with neem oil, which is an organic inhibitor.[8] Germany introduced mandatory application of urease inhibitors in 2020.[9] England introduced similar rules in 2024, while UK’s Sustainable Farming Incentive (SFI) is supporting adoption of inhibitors and novel fertilizers.[10] The European Environment Agency (EEA) requires all its members to reduce ammonia emissions by 2030, so more European countries may introduce policies regulating urea application in the coming years.[11] USDA is also offering incentives for farmers applying inhibitors as a part of the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP).[12]

Exhibit 6. How nitrogen fertilizers are converted into plant nutrients

Source: RMI

Different properties of nitrogen fertilizers

Although all nitrogen fertilizers have the same purpose of providing nitrogen to plants, they are very different in many ways. To maximize nitrogen use efficiency and increase yields, applied fertilizer should match the cultivated crop and application conditions. Given the significant variations in cultivated crops, climate, soil profiles, agricultural practices and available infrastructure around the world, various nitrogen fertilizers play different roles in global markets (Exhibit 8).

Due to different chemical properties, nitrogen fertilizers have different effects on soil acidity. Fertilizers containing ammonium are the most acidifying, while nitrate-based options have a smaller effect on soil pH. This is an important aspect, as soil acidity affects availability of other nutrients in the soil, meaning that excessive fertilization can harm yield. Soils need a careful balance: while micronutrients (like iron, manganese and zinc) are more available in acidic soils, macronutrients (NPK) generally require neutral or slightly acidic soils. Unsurprisingly, crops are also sensitive so soil acidity, so farmers often necessitate application of additional materials to adjust soil pH through liming or acidification.

Technology tree (Exhibit 7) shows the variety of nitrogen fertilizers. Ammonia takes the central part in this scheme, being a building block for many fertilizers. This way green ammonia production enables a variety of low-carbon solutions with different features. Besides simple options, like anhydrous ammonia or urea, there are complex fertilizers, like UAN or CAN. These advanced solutions effectively combine beneficial properties of all components. For example, nitrate in CAN in readily available for plants, while ammonium provides a delayed release due to the required nitrification process. Calcium, besides being a plant nutrient, also adjusts soil acidity, balancing out acidification caused by ammonium.

Exhibit 7. Low-carbon nitrogen fertilizer production processes derived from green ammonia

Source: RMI

Exhibit 8. Market shares of nitrogen fertilizers around the world

Most popular nitrogen fertilizers

Anhydrous ammonia (AA, 82% N) is widely used in the United States. As anhydrous ammonia is a pressurized gas fertilizer, its storage, application, and transportation require complex infrastructure and machinery. Demand for AA in the United States is driven by large-scale farming of nitrogen-intensive crops such as corn in the Midwest. High nitrogen content and abundant domestic natural gas resources also make AA the most economical nitrogen fertilizer in the United States.

In contrast to the United States, EU farms are smaller and more fragmented, making the machinery and infrastructure required for AA application economically impractical. Although both the United Stated and EU regulations recognize AA as a hazardous material that poses environmental and health risks, EU safety and environmental regulations are more stringent, making urea and nitrate fertilizers the typical choice. As ammonia is acknowledges as a major air pollutant in the EU, emission reduction targets also indirectly discourage the use of ammonia as a fertilizer.

Ammonium nitrate (AN, 34% N) is a popular solid fertilizer in Europe, with a smaller market share in the US. It is well suited for mild weather applications, as part of nitrogen it contains is already in the nitrate form and is immediately available to plants, while the ammonium portion releases nitrogen more slowly due to nitrification. AN is sensitive to temperature, and when temperature raises over 32°C AN substantially increases in volume. If the fertilizer goes through several such transitions during storage, it can break down into fines. To prevent this, stabilizers can be added to the product. AN is also hygroscopic, requiring moisture control during storage.

In contrast to AA, the regulation of AN in the United States is more stringent than in the EU, as safety concerns outweigh environmental considerations. Because AN can be used as an explosive, the handling of AN is highly regulated in the United States. As a result, AN is frequently used in fertilizer mixtures, e.g., calcium ammonium nitrate (CAN, 26%–28% N), which is a stable material. Alternatively, AN can be dissolved in water and be applied through irrigation systems.

Today, urea (46% N) is the most consumed type of nitrogen fertilizer. First commercial production started in 1920s. Initially, urea was not widely adopted, being a slow release fertilizer. Production of urea is integrated in fossil-based ammonia synthesis process, utilizing high pressure and carbon dioxide from the ammonia cycle. Several methods exist to produce solid urea, either for compound fertilizers or straight application.

Solid urea storage is straightforward, contributing to its use in international markets. Urea is hygroscopic, requiring humidity control during storage to prevent caking or dust formation. Moreover, urea also requires certain application procedures. Urea and urea-containing fertilizers have the highest volatility losses among other nitrogen fertilizers. Immediate incorporation of urea into the soil is an effective way to reduce these losses. Moreover, application of urease inhibitors can be an effective way to mitigate nitrogen loss. In ideal case, urea is also applied before rainfall, as adequate moisture can further improve its efficiency. Inefficient urea application can result in increased application rates. As urea acidifies soil, limiting availability of nitrogen, inefficient fertilization creates a self-reinforcing cycle.

Another mitigation option is the use of slow-release coated urea. There are several types of slow-release NPK fertilizers besides urea with different coating types, and those using polymer coating pose significant environmental risks. Studies show that both conventional and biodegradable plastics from these products can negatively affect soil fertility, soil microbial composition, and can create microplastic pollution.[13]

Urea production is well combined with ammonium nitrate production. Both materials are synthesized in a liquid form, so urea ammonium nitrate (UAN, 28/30/32%) solution can be produced in a rather simple way and allows several nitrogen content levels. Being a non-pressure nitrogen solution, UAN offers several solid benefits to farmers. Field application of UAN is easier and more uniform, compared to anhydrous ammonia. UAN can be mixed with other NPK solutions and pesticides, also allowing injection into irrigation systems. UAN requires certain storage arrangements, as it tends to crystallize in the bottom of storage tanks. As a liquid solution with moderate nitrogen content, UAN has a higher transportation cost compared to urea.

Ammonium phosphate is a phosphate fertilizer and due to its wide adoption, it is also a major source of nitrogen. Ammonium phosphate is produced either as monoammonium phosphate (MAP, 62% P2O5 and 12% N) or a diammonium phosphate (DAP, 54% P2O5 and 21% N). The process entails ammoniation of phosphoric acid. MAP and DAP are stable compounds and are easy to store and transport, showing low hygroscopicity.[14] They can be applied either in solid form or be dissolved in water and distributed through irrigation systems.

Table 1. Property comparison of common US nitrogen fertilizers

Identifying Challenges

The recent innovations in ammonia technology have shown the potential for sustainable methods of ammonia production as well as alternatives to the Haber Bosh process altogether. As ammonia’s role in the energy transition continues to grow, reducing fossil fuel dependence and supporting technology innovation will become even more important in the near future. The path to a low-carbon ammonia industry will require multi-pronged investments in technology, infrastructure, and policy support. Collaborations across industries, governments, and academia are essential to advance these technologies, drive down costs, and scale production to meet global demand.

To better understand the current barriers preventing fast deployment of low-carbon fertilizer technologies and the green transition of the fertilizer market, RMI established an Ammonia Stakeholder Working Group (ASWG). Divided into two subgroups, the ASWG consisted of 14 industry stakeholders and 10 policy groups. The industry group included ammonia OEMs, project developers, farming and energy cooperatives, and a bank. This coalition focused on identifying both supply- and demand-side barriers and formulating solutions, for which the insights were used to generate educational materials about modern fertilizer technologies and market opportunities, as well as providing feedback to the ASWG policy coalition.

On the demand side, the pricing of carbon-free and low-carbon fertilizers is considered the most significant barrier to their adoption. Unless these products are cost-competitive with grey fertilizers or offer additional benefits such as price stability, they will not find significant demand. ASWG members also highlight that the lack of low-carbon fertilizer standards also contributes to a limited demand. As fertilizer production pathway doesn’t affect fertilizer properties and application procedures, switching to a low-carbon product can be seamless. Switching to a different nitrogen fertilizer type, on the other hand, is complex. While such a transition could improve nitrogen use efficiency and reduce fertilizer emissions, it would require changes in machinery and infrastructure, as well as application practices.

On the supply side, our ASWG members identified several barriers for low-carbon fertilizer project development. Novel technology projects have higher financing risk than conventional technology projects, forcing project developers to raise funds at higher interest rates. Long-term offtake agreements could potentially lower the financing risk, demonstrating a forecastable revenue stream for the planned project. Unfortunately, long-term offtake agreements are not used by farmers, who typically engage in short-term contracts. New fertilizer projects often necessitate long and costly pre-feasibility studies, which creates a certain market barrier for small-scale players. Besides that, project developers point to a complicated and lengthy permitting process and a long interconnection queue. Since it may not be feasible for small projects to build own renewable energy generation capacity, fertilizer facilities are forced to compete for green electricity in the market. Another identified challenge is the lack of ammonia storage infrastructure.

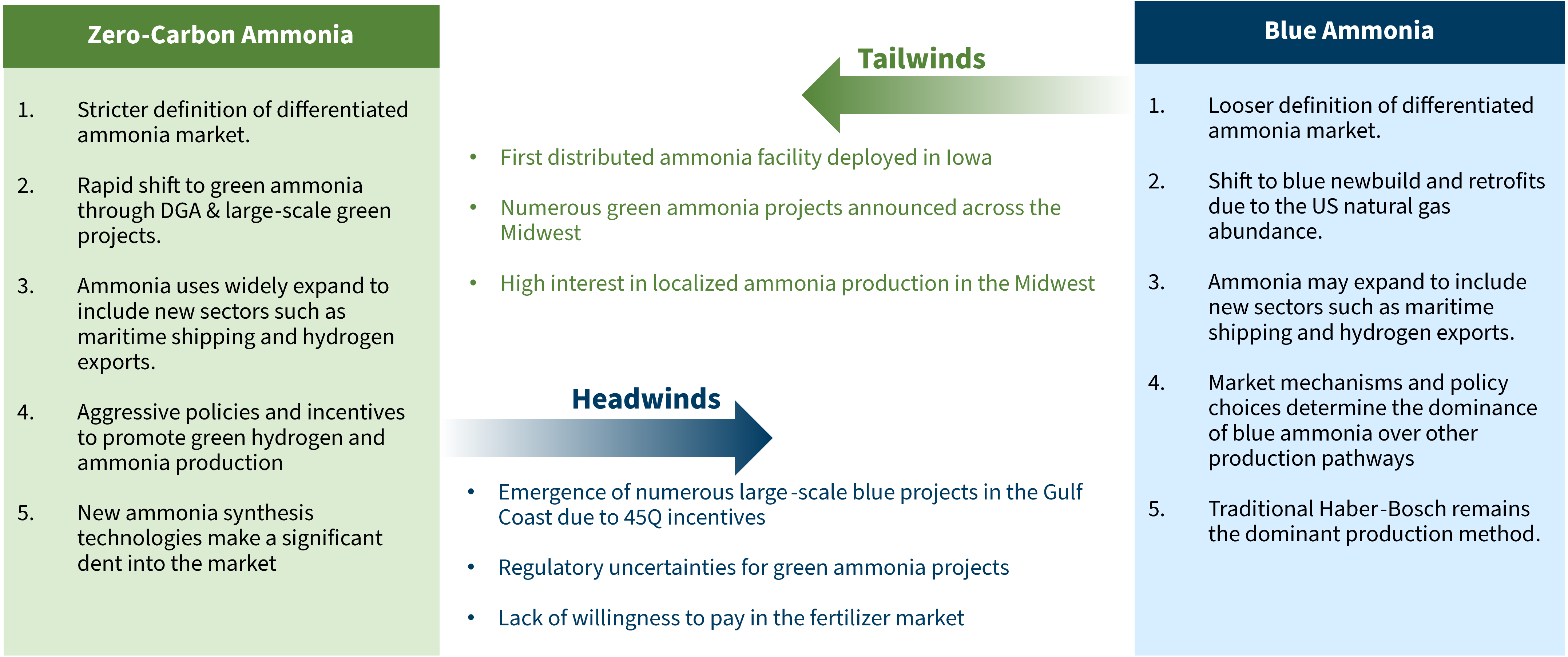

Lastly, it’s important to recognize current market dynamics. Though green ammonia and blue ammonia are both applicable and commercially ready strategies for decarbonizing the industry, there are major roadblocks preventing green ammonia from playing the leading role (see Exhibit 9).

Exhibit 9. Market challenges and opportunities for green and blue ammonia

Supporting Low-Carbon Fertilizers

Producing clean fertilizers from low-carbon hydrogen in a disaggregated pathway and mitigating the risks and challenges involved, will require policy support and incentives at all levels of government.

In-state incentives

From helping support reducing clean hydrogen costs to targeted in-state fertilizer production incentives, states have a toolbox of measures that can be implemented to facilitate the deployment of green ammonia. Below is a list of measures that states have implemented these past few years that can create an enable environment for green ammonia green fertilizer production.

1. Green Ammonia-Specific Public Support Programs

North Dakota passed legislation to approve funding for $125 million in a fully forgivable loan, with specific application for fertilizer facilities that utilize hydrogen produced from electrolysis. The North Dakota Industrial Commission upon reviewing the project decided to split the funding between two projects: $75 million to Prairie Horizon and $50 million to NextEra Spiritwood. After withdrawal from Prairie Horizon, the entire sum went to NextEra. Upon completion of the project and sale of 75% of the facility’s nameplate capacity, the entire loan will be entirely forgiven.

Similarly, Minnesota has officially rolled out a $7 million grant application process for green fertilizer production. The grant offers to support the development of a green ammonia industry within Minnesota for electric and agricultural cooperatives, provided that a long-term offtake agreement is signed and a cooperatives members obtain training in nutrient best management practices.

These fundings specifically aim facilitating green ammonia production, making them the most direct tool to scale the technology to commercial maturity and support the production of ammonia fertilizer derivatives with a smaller carbon footprint.

2. Clean Hydrogen and Renewable Energy Projects Support

Targeted hydrogen incentives address one the key cost components for ammonia production. Illinois passed legislation creating a $10 million-per-year tax credit for clean hydrogen users in 2026 and 2027. This hydrogen tax credit could support green ammonia production too. New York recently approved $8 million to fund projects that can both demonstrate and deploy cost-efficient clean hydrogen production integrated with renewable energy.

Supporting renewable projects at large can also be helpful tool to improve the economics of green ammonia projects. Minnesota recently established the Minnesota Climate Innovation Finance Authority (MNCIFA) to help meet the state’s ambitious clean energy goals. MNCIFA targets projects in Minnesota that face financial barriers not met by existing private market tools. North Dakota also passed legislation allowing entities to request up to $250 million in long-term, low-interest loans from the Bank of North Dakota and $25 million in grants for renewable energy projects at large.

Lowering financing costs could make localized, or disaggregated, green ammonia competitive with traditional ammonia production. Programs of these types can reduce cost barriers, accelerate operational projects, and prove the commercial viability of DGA. Further, the substantial community benefits of local production, the boost to renewable energy infrastructure, and the generation of new green jobs in farming communities are clear positives for states. Other states can replicate these programs, as they have demonstrated economic benefits, with the potential for multiple end-users beyond DGA.

3. Economic Development Boost

Creating an enabling environment is also crucial to scale green ammonia technology. Michigan uses its state university research network to attract investors looking for a highly educated workforce. Nel Hydrogen, a Norwegian hydrogen company, selected Michigan for its new gigafactory to produce electrolyzers for green hydrogen production. This project is expected to create over 500 jobs and generate nearly $400 million for the local economy. Nel Hydrogen credited Michigan’s engagement, outreach, and financial support as key factors in its decision. The project benefits from a $10 million Michigan Business Development Program grant. The Michigan Strategic Fund (MSF) board also approved a 15-year, 100% State Essential Services Assessment Exemption, valued at up to $6.25 million, to support the project.

National-level incentives

Disclaimer: This section reflects the understanding as of 02/14/25 and is subject to change.

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) includes clean electricity and hydrogen production incentives. New tax credit incentives and pilot projects such as the 45V credit and the Department of Energy’s (DOE) hydrogen hubs program point to support for reducing the financial and technological gaps of disaggregated electrolyzer and ammonia synthesis facilities.

1. Inflation Reduction Act

The IRA provides several incentives that can facilitate DGA project development. The 45V clean hydrogen production tax credit is the most important incentive to develop DGA. This technology-neutral credit offers up to $3/kg of hydrogen produced with less than 0.45kg of carbon dioxide equivalent per kg of hydrogen produced.

Additionally, incentives include the 45Y clean electricity production tax credit and 48E clean electricity investment tax credit. These credits provide tech-neutral production or investment tax credits (must select one) for qualifying zero-carbon facilities producing electricity. When meeting apprenticeship and wage requirements, and considering inflation rates, the production tax credit (45Y) has a current base rate of $0.0275/kWh. There are further 10% bonuses for meeting domestic content requirements and locating in an energy community.

The investment tax credit (48E) provides a base credit of 6% of qualified investment but can go up to 50% with domestic content requirements, locating in an energy community, prevailing wage, and apprenticeship requirements. Initial guidance on prevailing wage and apprenticeship requirements can be found here.

2. 45V: Credit for Production of Clean Hydrogen

The Biden-Harris Administration issued the final rule on January 10th, 2025, for 45V, the key tax credit for hydrogen. The final rule establishes a clear, workable framework for clean hydrogen development while maintaining environmental integrity. This framework is important because it’s the first national electricity accounting system and could be built upon for trade and other lifecycle emissions (LCA) based policies down the line.

The rule establishes an accounting framework for projects to follow. The rules maintain the “three pillars” overall structure — requiring producers to build and deliver clean power, at the time of production, to hydrogen projects to qualify for the tax credit. The rule creates a market-driven system where regions with the strongest clean energy deployment will offer the most competitive opportunities for hydrogen production.

The “cleanest” hydrogen receives a credit of $3.00 per kilogram if the lifecycle GHG emissions are less than 0.45 kilograms of CO2e (CO2 equivalent) per kilogram of hydrogen produced. Hydrogen that has lifecycle GHG emissions greater than 4 kilograms of CO2e per kilogram of hydrogen cannot receive a credit. The table below presents each tier of credit value for the section 45V credit:

Table 2. The Clean Hydrogen Production Credit: How the incentives are structured, Congressional Research Service

Conclusion

Nitrogen fertilizers are an essential part of modern agriculture, and ammonia plays a central role among all synthetic nitrogen fertilizers. While anhydrous ammonia is a widely used fertilizer in the United States, it is also a building block for the production of several different nitrogen fertilizers. In this way, large-scale clean ammonia production unlocks a variety of low-carbon fertilizers with unique properties and different applications.

There are a number of emerging ammonia production technologies that offer an alternative to the conventional Haber-Bosch process. These technologies are at various stages of readiness. If proven viable, they may unlock better energy efficiency, lower production costs, and a reduced carbon footprint compared to a fossil-fueled Haber-Bosch process. Moreover, the described technology field also offers optionality of the ammonia production model, as in some market and application environments small-scale local production facilities can be cost-competitive with bulk producers and benefit local societies. Besides creating a resilient fertilizer supply guarded against market price volatility, such disaggregated ammonia production can boost local infrastructure investments and create jobs in rural areas.

Through engagement with ASWG members, we have identified several barriers to the development of novel technology projects. These challenges include limited demand for low-carbon fertilizers and lack of industrial standards that differentiate fertilizers based on the carbon footprint of their production. In addition, ASWG members point on higher financing risks of novel technology projects, long and costly pre-feasibility studies, lengthy permitting process, lack of ammonia storage infrastructure, long interconnection queues, and intense competition for renewable energy.

Efforts to support local fertilizer production projects are also emerging in several states. These include loan and grant programs and tax credit mechanisms. As green ammonia and especially DGA models are still a nascent sector, accelerated efforts are required to target existing regulatory, financial, political, and technological challenges. Despite this, the benefits — boosting local economies, improving agricultural output, and reducing emissions for all nitrogen fertilizers — make it a promising solution for the future. Using existing policy levers can provide the necessary support for green ammonia. Prioritizing grants, federal- and state-level incentives, and loans for commercial deployment, leveraging higher education systems, and establishing pilot projects are all examples of best practices that can significantly aid the development of low-carbon fertilizer technology.

- Prioritize Grants, Incentives, and Loans

- States can prioritize grants, incentives, and long-term, low-interest loans over one-time tax credits or annual payments. The certainty provided by loans or grants offers distinct terms for investors and allows for commercial deployment of green fertilizer technology. As an alternative to states providing loans to project developers, states can act as guarantors of those loans. This model can be less capital intensive for states. Commitment to long-term funding serves as a strong example of the necessary stability for low-carbon ammonia projects.

- Leverage Higher Education Systems

- Leveraging higher education systems to attract R&D investment from prospective companies and conducting localized research at flagship universities can accelerate technology development and stimulate practical application of green fertilizers.

- Emerging Technology Support

- A national focus on international competitiveness calls for the creation and validation of pilot projects that stem from research and development funds: resources traditionally directed toward innovation and competitiveness. These projects could explore additional hydrogen applications and focus on low-carbon ammonia technology.

Shifting the market away from the few players that dominate the ammonia market would spur competition, generate market-driven innovation, and revitalize local economies in critical regions. Localized fertilizer production empowers farmers and agricultural co-ops by providing agency in the fertilizer industry while lowering costs.

The combination of these policy tools will help accelerate the deployment of green fertilizers and catalyze the market into this direction, fostering a resilient and sustainable future for farmers and rural communities in America.

Endnotes

[1] Greenhouse gas emissions from nitrogen fertilisers could be

University of Cambridge https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk › download

[3] https://www.ifastat.org/databases/graph/1_1

https://www.datawrapper.de/_/2kKvM/

[4] Pardey P.G., Alston J.M.“Unpacking the Agricultural Black Box: The Rise and Fall of American Farm Productivity Growth”, The Journal of Economic History. 2021;81(1):114-155.

https://www.datawrapper.de/_/reuBJ/

[7] https://www.ifastat.org/databases/plant-nutrition

[8] https://www.fert.nic.in/sites/default/files/What-is-new/Neem-Coated.pdf

[10] https://ahdb.org.uk/news/how-do-new-rules-on-urea-use-in-england-affect-farmers; https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/sustainable-farming-incentive-guidance#sustainable-farming-incentive-scheme:-expanded-offer-for-2024

[11] https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/newsroom/news/key-air-pollutant-emissions-decline-across-the-eu

[12] https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/programs-initiatives/eqip-environmental-quality-incentives

[13] Wenjie Guo, Zhiwei Ye, Yanna Zhao, Qianle Lu, Bin Shen, Xin Zhang, Weifang Zhang, Sheng-Chung Chen, Yin Li, “Effects of different microplastic types on soil physicochemical properties, enzyme activities, and bacterial communities”, Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety,Volume 286,2024,117219,ISSN 0147-6513,https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2024.117219.