Creating Energy Independence in the High Arctic

In remote Kotzebue, Alaska, wind and solar provide peace of mind

Even in oil-rich Alaska, energy access doesn’t come cheap. The “last mile” can often be the most expensive part of the process. This is especially true in Kotzebue, Alaska, a city of 3,000 people 26 miles inside the Arctic Circle.

No roads lead here. Year-round access is only available by air (unless your approach is by snowmobile or dog sled). Barges can only arrive in the warmer summer months when the sea ice thaws.

Its remoteness means Kotzebue, like many of Alaska’s coastal towns and villages, relies on its own microgrid for electricity.

Kotzebue has long relied on diesel generators for power, with the fuel shipped in annually. Making electricity this way comes at a cost: Kotzebue’s leaders have to accept whatever fuel prices the market dictates at the time, a variable over which they have no control. They also have to wait until the sea ice thaws for any hope of resupply.

A hard look at the cost and reliability of the status quo, as well as a dose of visionary thinking, made Kotzebue consider different sources of power. Today, the community is a leader in renewable energy, and has encouraged similar Alaskan communities to follow its lead.

By adding wind, solar, and battery storage, diesel deliveries now count for less of the energy mix, insulating the community from fuel price spikes and providing peace of mind.

“We never know from year to year what the price of diesel is going to be,” says Tom Atkinson, the general manager and CEO of Kotzebue Electric Association (KEA), the minigrid operator which acts as the local utility.

“So we’re kind of held hostage to that. And that is a direct pass through to our community for energy costs. So the more we can take that out of the equation, the more affordable we can make energy for our community.” Atkinson estimates that wind, solar, and battery additions have allowed Kotzebue to displace 350,000–400,000 gallons of diesel annually.

When RMI visited in May as part of an educational partnership with the Alaska Center for Energy and Power (ACEP) the sea ice was still thick. Kotzebue Sound, on the edge of the Chukchi Sea to the town’s west, becomes a highway in winter for hunters seeking seal, whale, and caribou and for ice fishing. Hunting and fishing have been part of life here for more than 10,000 years, and that self-reliance continues to make sense when the price of meat and other staples — $12.99 for a gallon of milk — is high.

If using the land around you for sustenance is the right call for locals in Kotzebue, the same is true for energy. Abundant wind and almost endless summer sunshine make wind turbines and solar panels a lifeline, and they have allowed Kotzebue, bit by bit, to become less dependent on outside sources to keep the lights, and everything else, on.

“For the past 30 years, the driving factor has been about creating resilience,” Atkinson says. “The more we decrease the amount of diesel that we have to burn to generate electricity, the more we create greater energy independence.”

Welcome to Kotzebue

Named for a German who explored the area on behalf of Russia, the town is known as Qikiqtaġruk by the native Iñupiat who have lived in the region for more than 10,000 years, descended from those who first crossed the Bering Strait. The town’s demographics reflect that heritage: Iñupiat people make up over 75 percent of the population today.

With over 3,000 residents, Kotzebue is by far the most populous settlement within Alaska’s Northwest Arctic Borough, an administrative division similar to a county (although such comparisons fail to capture that the borough’s size, at 40,000 square miles, is larger than 13 US states). Kotzebue is governed by both the municipal and tribal level; the Native Village of Kotzebue is the federally recognized tribal government while the City of Kotzebue operates under a mayor and city council.

Kotzebue serves as a key port and airport for the rest of the borough as well as a source of employment in health care, education, and government.

First in the World: Kotzebue’s journey from planning to power

But harnessing the wind wasn’t always such a no-brainer. In fact, before Kotzebue, utility-scale wind generation in the Arctic Circle had never been done. In the early 1990s, Kotzebue partnered with Alaskan state energy agencies and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory to prove the concept could work, and by 1997 had three 66 kWh AOC wind turbines operating.

Along with the usual planning, permitting, and cost issues such an ambitious project runs into, officials also had to reckon with the unique geographical challenges. Namely, how to mount a 100+ ton turbine on soil that freezes solid in the winter and turns to mud in the summer. The solution? Thermopiles, specialized poles drilled into the earth that help move heat and keep the foundations frozen solid. Like the wind turbines themselves, the thermopiles are an example of how knowledge of the land paired with technical know-how can solve a complex problem.

As wind technology has advanced, so has Kotzebue’s wind farm. Today, the area south of the town looks like a wind energy museum. Decommissioned turbines sit idle next to their modern counterparts: currently two 1 MW EWT turbines. But the town knows that nothing should go to waste, and there are plans in place to retrofit and recommission some of the older turbines to add additional power.

In the meantime, they have put the old turbine interconnections to good use, hooking them up to a 1 MW solar array. And this added energy comes with storage. In 2015, Kotzebue added a 1.2 MW battery with special cold weather characteristics to help balance loads and store excess energy.

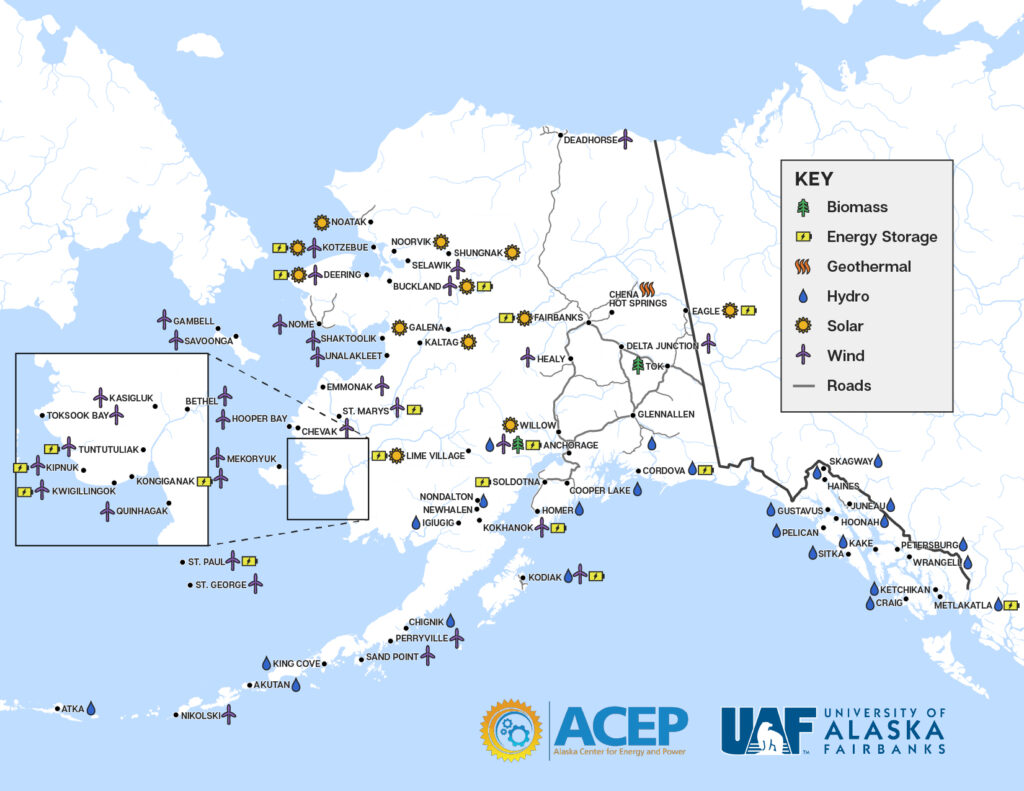

By utilizing grant programs both within Alaska and at the federal level, Kotzebue has helped keep capital expenses low, further aiding customers. And Kotzebue is not alone, dozens of communities across the state have turned to renewables to supplement their microgrids.

Kotzebue (top left) is part of a wider array of “islanded” microgrids that keep Alaska’s rural communities plugged in. Many are adding renewables as a response to high diesel costs. Image credit: Gwen Holdmann, Richard Weis, University of Alaska, Fairbanks.

Kotzebue (top left) is part of a wider array of “islanded” microgrids that keep Alaska’s rural communities plugged in. Many are adding renewables as a response to high diesel costs. Image credit: Gwen Holdmann, Richard Weis, University of Alaska, Fairbanks.

“The more we decrease the amount of diesel that we have to burn to generate electricity, the more we create greater energy independence.”

Tom Atkinson, general manager and CEO of Kotzebue Electric Association

Even as renewable energy has added capacity and reduced strain on the town’s finances, diesel remains a key part of life in Kotzebue. The enormous fuel storage tanks, visible from blocks away, need refilling every year. Kotzebue’s location means fuel deliveries can only happen in the summer months when barges can navigate ice-free waters.

But that one-time delivery window comes at the cost of point-in-time prices. At the mercy of markets rocked by geopolitical tensions, war, and other supply challenges, Kotzebue’s officials must accept whatever price is set — making it difficult to plan ahead. Despite Alaska’s oil wealth, the fuel is not even homegrown and is purchased from a Canadian supplier.

That volatility has only given local leaders greater ambition to break free of the strictures of fossil-fuel dependency. Plans are in place to increase wind and solar generation further to meet a goal of 50 to 60 percent renewable generation by 2030. Even with recent federal rollbacks on renewable energy initiatives, Atkinson is confident that this has only slowed, but not stopped, the town’s momentum.

The biggest setback, Atkinson says, is the delaying of plans for another 2 MW wind operation on tribal land, which KEA planned to then purchase energy from. Atkinson laments the loss, because: “it would create more energy dollars staying in the community, which is important to us.”

“When you spend your money on diesel, money just goes out of the community, out of the state,” Atkinson says. “So we think that we’re going to get there eventually. It’s just going to take us a little longer than we thought.”

The author wishes to thank partners at the Alaska Center for Energy and Power (ACEP) at the University of Alaska Fairbanks for their support for this article and on the ground in Kotzebue.

To learn more about the Energy Leadership Accelerator, visit the ELA website.

Additional resources:

Driving below zero

Even with gas prices at $8 a gallon, Kotzebue’s entire electric vehicle fleet stands at two, both under the ownership of the Kotzebue Electric Association. The first, a Nissan Leaf, can amble quietly around the town, but the latest addition, a Ford F-150 Lightning, is designed for harder work.

“Oh, there’s always a fight in the morning over who gets the keys,” KEA’s Atkinson says of the Ford’s popularity. Analysts like how they can plug their laptops right in to the car, technicians can do the same with heavy equipment thanks to the truck’s 220v outlet, while everyone else enjoys how quickly the car warms up. Sure enough, when RMI visited KEA in May, the Ford was already out on a line repair job.

The reality of EV adoption in somewhere with as harsh winters and high electricity prices as Kotzebue is complex: on the one hand, just keeping the driver and passengers warm drains battery life significantly, but on the other, extensive use of block heaters on gasoline-powered cars, as well as the fuel draw during idling, means that there are quite a few instances where an EV can make economic sense.

Kotzebue’s small but mighty EV fleet shows that even in the Arctic, electric vehicles can be a viable solution in certain cases.