Department of Commerce in Washington DC, America. American flag flying.

Reducing Energy Costs in Federal Buildings

U.S. federal buildings make up the largest portfolio of buildings in the world. Ranging from offices to military bases to national labs, they not only provide space for hundreds of thousands of federal employees to provide critical services to our country, but also represent a significant opportunity to save energy and money, and at the same time create jobs and stimulate economic growth—all while contributing to CO2 reduction goals.

The U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) newly released U.S. Energy and Employment Report estimates that overall energy-related employment represented 31 percent of the total U.S. construction labor force in 2016, up from approximately 27 percent in 2015. The DOE also projects that the number of construction workers in the energy-efficiency segment will increase by 10.6 percent in 2017.

Whether you measure success through jobs created, taxpayer dollars saved, or tons of carbon reduced, the massive “size of the prize” is one key reason the federal government has established itself as a leader in energy-efficient buildings. And even though the fate of many federal initiatives are uncertain due to a change in administration, federal buildings are and always will be a ripe opportunity to reduce government waste, increase public-private partnerships, and increase value to the taxpayers while maintaining U.S. leadership and energy independence—a goal spanning political party lines.

So far, federal agencies have shown significant progress in meeting cost- and energy-reduction goals. Yet there still remains a significant need for continued emphasis on deep energy retrofits of federal buildings and the development of pathways toward net-zero energy buildings that go far beyond current levels of energy use reduction. But how?

LEVERAGING THE BEST TOOLS TO GET THE JOB DONE

The federal government has relied heavily on a blend of direct obligations (funds appropriated by Congress), energy savings performance contracts (ESPCs), and utility energy service contracts (UESCs) to improve building performance for the past eight years.

ESPCs allow agencies to partner with energy services companies (ESCOs) to finance the upfront costs of retrofit projects through their long-term energy savings. This approach requires no upfront capital costs or special appropriations from Congress, which makes it attractive to agencies. The ESCO’s guaranteed energy cost savings are used to pay back the initial cost of implementing the measures. UESCs are similar mechanisms, and use the utility directly rather than an ESCO. When appropriated funding is available, it can pay for energy projects directly, but can often drive greater value by being incorporated into existing ESPC projects.

HELPING THE NATION’S LARGEST LANDLORD DRIVE DEEPER SAVINGS

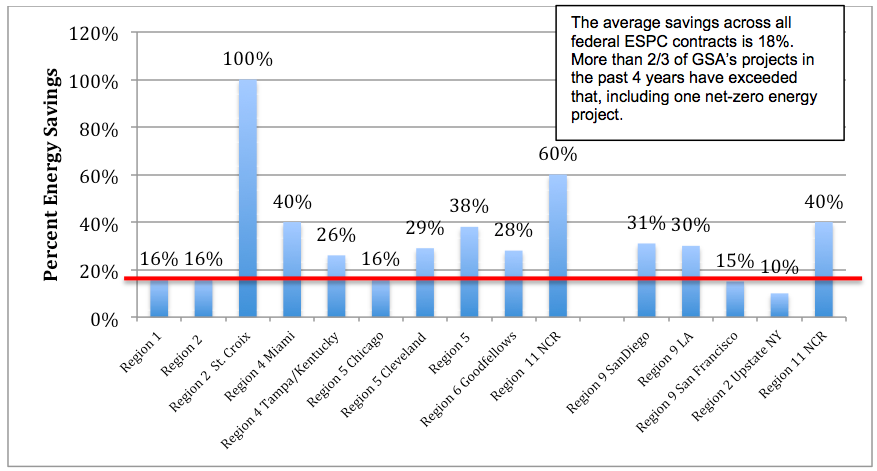

Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI) has worked with the U.S. General Services Administration (GSA)—the nation’s largest landlord—for the past five years to drive deeper energy savings in these crucial ESPC/UESC contracts. This work has enabled the GSA to more than double the average federal energy savings of 18 percent to 38 percent in a group of 10 projects awarded in 2012, totaling $172 million in investment. The GSA has replicated this higher saving level in the most recent round of projects awarded in 2016, with three of the five contracts awarded achieving energy savings greater than 30 percent. More than two-thirds of the 15 contracts GSA executed in the past four years exceeded the federal average savings.

Energy savings from the GSA’s National Deep Energy Retrofit Program projects

Throughout our time contracting for the GSA, we documented many lessons learned and case studies highlighting the application of integrative design principles and load-reduction strategies under the ESPC construct. At the top of the list of lessons learned are taking a long-term and holistic perspective on planned infrastructure upgrades, engaging all stakeholders early and often, and analyzing the full value of benefits within the maximum 25-year federal contract period.

For example, the Region 9 project in San Diego (included in the figure above) incorporated some notable load-reduction strategies. Measures included a new highly insulated roof, window inserts to reduce heat gain and infiltration, solar photovoltaics, and battery storage to provide peak demand reduction.

The National Capital Region project included three historic buildings that were updated to improve occupant comfort and productivity. One building in particular—although only 10 years old—had HVAC issues stemming from its original design that caused the top floor to overheat in the summer. The ESPC enabled the relocation of underfloor air-distribution vents, which rebalanced the entire system and significantly improved the comfort of occupants. Measures like this contributed to energy savings, but are not yet common in traditional ESPC contracts. Because of the commitment GSA has shown to increasing energy savings levels and strengthening relationships with ESCO partners, we expect this trend of above-average energy savings to grow.

Another important takeaway is that while ESPCs are considered the primary means to accomplish federal retrofits, blending ESPC funding with appropriated funding can both expand the scope and improve the value of federal deep energy retrofits. RMI collaborated with a number of federal stakeholders to share our insights in a white paper, which will be published in a forthcoming issue of the ASHRAE Journal.

Several agencies have taken note of the success that GSA has had in its National Deep Energy Retrofit program. The Army’s Net-Zero Initiative selected nine installations to pilot net-zero energy by 2020 for the purposes of increased resilience. More recently, the DOE has brought a heightened level of focus to the opportunity to go deeper.

THE DOE DEEP ENERGY RETROFIT CHALLENGE

DOE is the fourth-largest energy-using federal agency and operates offices and labs for more than 13,000 federal employees in more than 111 million square feet of facilities. This highly diverse portfolio provides many challenges and opportunities relating to deep energy retrofits, notably around increasing and streamlining the use of performance contracting, navigating a multitude of stakeholders, balancing campus-wide central plant improvements with building-level load-reduction strategies, and managing research-driven process energy loads.

In November 2016, the DOE announced its Deep Energy Retrofit Challenge to improve the efficiency of its facilities through retrofit projects that leverage performance contracting. The goal is to award a minimum of $125 million in performance-based contracts by the end of fiscal year 2018, producing deeper savings in treated facilities. The challenge supports the Executive Order 13693 requirement to reduce the energy use intensity of participating buildings by 25 percent by 2025 from a 2015 baseline. Buildings that realize energy-use reductions of greater than 40 percent will also be prime candidates for meeting the DOE’s goal of achieving net-zero energy, waste, or water in 1 percent of its existing buildings by 2025.

More importantly, the challenge can help drive agency resilience and enhance mission effectiveness, ensuring that important facilities experience less downtime, thereby helping federal staff do their jobs.

RMI is part of a core team driving the challenge, which also includes DOE’s Sustainability Performance Office and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. The team is orchestrating a collaborative approach of working with DOE stakeholders, site contractors, energy service companies, and utilities to develop a pipeline of projects suitable for deep energy retrofits and to improve integrative retrofit design processes and tools. Part of RMI’s role is to facilitate two stakeholder charrettes, the first of which took place December 2016 and explored process barriers and opportunities for deep retrofits, ways to enhance resiliency and pathways to net-zero carbon using ESPCs and UESCs, and how to build a network of support and innovation among key DOE stakeholders. A second charrette will be held in March 2017 to bring ESCOs and site-level stakeholders into the process.

Since DOE is one of the largest energy users among federal agencies, it will serve as a national leader in sustainable building infrastructure improvements. We look forward to sharing the progress and the experience of our program partners as the DOE Deep Retrofit Challenge realizes results.

Image courtesy of iStock.