European union flag against parliament in Brussels, Belgium

For the EU’s Groundbreaking Climate Law, Data is Key

For years, manufacturers have watched with apprehension as the European Union debated a policy that could send shockwaves across the world’s heavy industries. Europe’s aim: to level the playing field between EU companies that pay for their carbon pollution and those overseas that don’t.

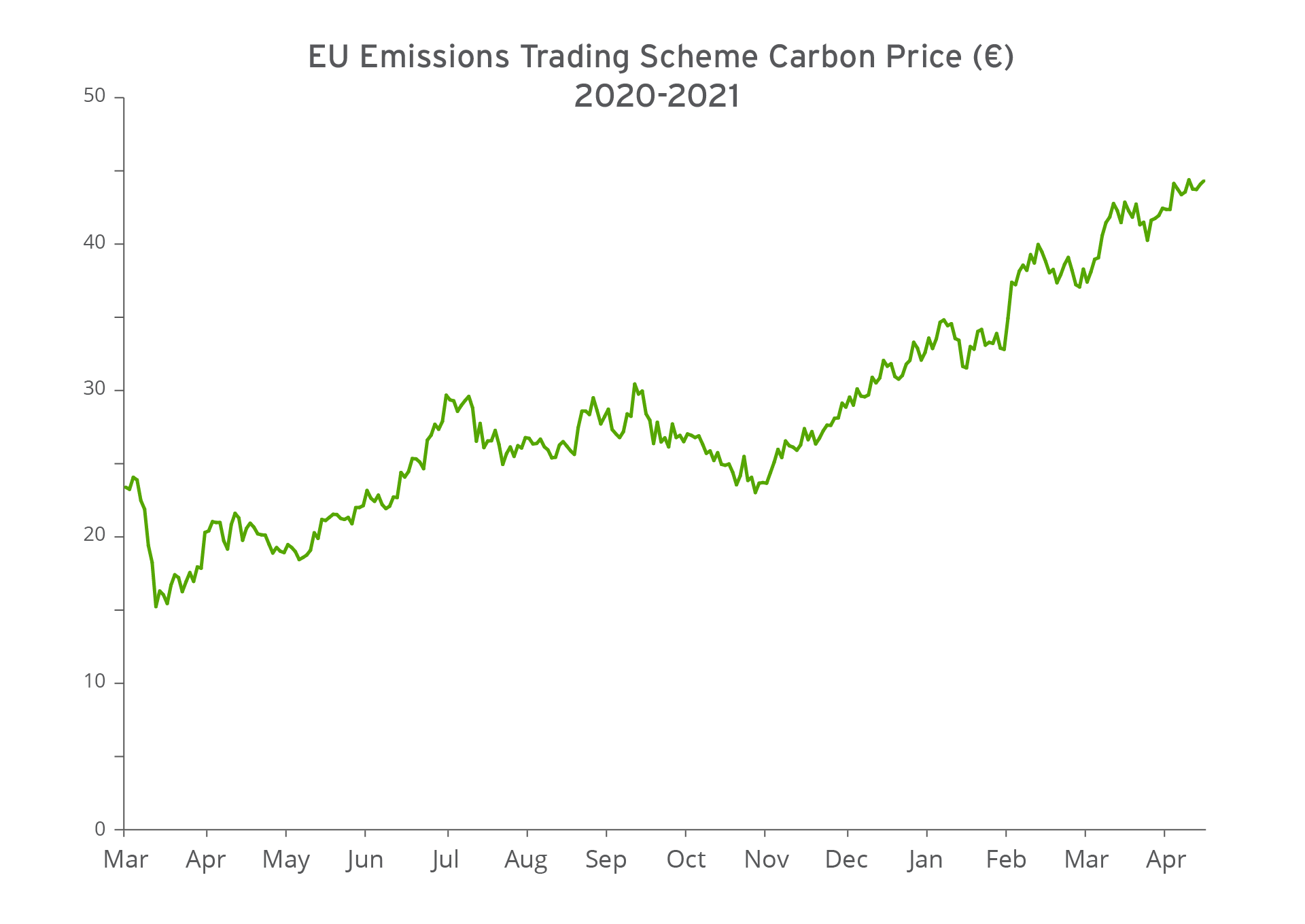

Consider steel. Across Europe, steelmakers are required to pay for their carbon pollution through the EU’s cap-and-trade system, known as the Emissions Trading System, or ETS. For years, the price of carbon on the European market was relatively low, leaving only a small footprint on industries like steelmaking.

But in the past year alone, as the European Union further committed to its ambitious climate targets, the price of carbon on the ETS doubled. As a result of the increased prices, European steel producers report that the cost of carbon alone now accounts for a staggering 10 percent of the final price of their products.

“With the increasing price, we get into a real problem,” Axel Eggert, the director of public affairs for the European Steel Association, told the Financial Times. “Our global competitors do not have those [same] carbon constraints.”

When European steel is priced for its carbon, steelmakers abroad who don’t pay to pollute gain a competitive advantage. The result? Dirtier steel from abroad enters the EU at a lower price.

In recent months, heavy industry groups across Europe have sounded the alarm. If Brussels doesn’t take action, they warned, then domestic manufacturing and heavy industry will be unable to compete—or will move offshore to countries with fewer regulations on carbon pollution. That outcome isn’t just bad for European manufacturers; it’s bad for the planet.

Today, we learned that the EU is taking action. Brussels announced a plan to tax carbon at the border for certain goods whose manufacturers did not pay a carbon price in their country of origin. As a result, companies that sell in the world’s largest single market will be rewarded for reducing emissions—and high-emitting firms will pay equally for their pollution, regardless of whether it takes place inside the EU.

Reading between the lines, the EU’s message to heavy industry across the world is clear: “If you won’t put a price on carbon, we’ll do it for you.”

A new era of climate policy—and a new set of challenges

The new policy, called the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), is the first of its kind anywhere in the world: a carbon-specific import tax. The new policy targets five heavy-emitting industries: iron and steel, cement, aluminum, fertilizer, and electricity generation. Cleverly, the CBAM carbon price is linked to the price of the ETS, which harmonizes the price of carbon for goods produced inside the EU and those produced overseas.

But an issue that has long loomed on the horizon suddenly requires urgent attention. No one can inspect a container of steel on a cargo ship in Rotterdam and determine how much CO2 was emitted in its production. That’s how commodities work: they’re designed to be identical.

The origins of these products matter. Steel produced in an electric arc furnace in Sweden has one-tenth the embodied carbon of steel produced in a traditional blast furnace in China. And the variation doesn’t stop there. Even within the same nation, a steelmaker that sources renewable electricity could have a substantially lower carbon footprint than one using coal-generated electricity.

Although commodities are identical, the process of manufacturing them is not. For the European Union’s boldest climate legislation to succeed, the market for these goods will need to remove the shroud of anonymity and allow information on emissions to follow products as they travel from mine to furnace to factory gate.

The challenge is straightforward, but the solution requires a renaissance in how embodied carbon is reported and measured along supply chains. For the first time, data will need to come from the asset level (i.e., the mine, mill, or factory) rather than industry averages that are routinely used in lieu of specific data.

Low-carbon producers have a clear incentive to lead the charge to asset-level data: to avoid overpaying taxes at the EU border. But the frameworks for recording and reporting these emissions are in danger of becoming a Wild West of data, particularly if the CBAM expands to include finished products (e.g., cars or home appliances), which would require integrating distinct measurement frameworks.

Without a revolution in carbon accounting, the EU may struggle to effectively implement CBAM. But with the necessary tools in place, the EU’s new policy could take flight, and fundamentally reshape commodity markets in the process.

Carbon accounting needs a digital future

For the first time, measuring embodied carbon in products like steel is no longer a simple issue for corporate sustainability reports—it’s a matter of international trade policy.

The Climate Intelligence team at RMI, together with our partners, is on a mission to build the architecture that will allow trade blocs, nations, private firms, and individuals to track the carbon footprint of the goods they purchase, even from the far side of the value chain.

The goal: to build a digital infrastructure for tracing embodied carbon along the chain of custody. This work will be successful when seemingly identical commodities, such as steel, can be distinguished by their emissions intensity. This will enable policymakers to level the playing field and allow investors and buyers to meet their climate targets.

How will we do this? By creating a system of digital barcodes that follow physical goods even as they move through the various steps of a supply chain—like how a restaurant bill follows the gregarious patron who moves between tables during the course of a long evening.

We could hardly manage this task alone. Our partners, particularly those at the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, the Mission Possible Partnership, and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, are playing critical roles to help us develop actionable tools to drive deep decarbonization.

There’s an old saying: “you can’t manage what you don’t measure.” This is especially true for carbon pollution. But as the EU’s announcement shows, the practice of carbon accounting is at an inflection point. There are clearer skies on the horizon.