Electricity Customers Are Getting Burnt by Soaring Fossil Fuel Prices

“Cost sharing” between customers and their utilities could have saved ratepayers at least $2 billion during the height of the pandemic

In the wake of 2021 winter storm Uri, natural gas and wholesale electricity prices spiked across the Midwest and Great Plains. Now, months later, utilities in those states are going back to state regulators demanding the ability to recover the costs of that energy from customers. In Minnesota, one utility is asking to recover $466 million in unexpected costs. Xcel Energy, which operates in both Minnesota and Colorado, estimates that it incurred $1 billion in unexpected costs.

But rather than letting utilities pass these extreme costs on to their customers, a simple policy change would have saved customers at least $2 billion over the two-year period between 2020 and 2021 when families in the United States were also dealing with the hardships of COVID: fuel cost sharing.

What Is Fuel Cost Sharing?

When a utility burns fuel to make electricity, it has to pay for the fuel, but those costs are then passed through to the customer. No mark up, no discount — fuel costs are simply a pass through. What this means is that for vertically integrated utilities — utilities that own generation, transmission, and distribution — fuel is not a source of either costs or profits.

Most utility investors don’t even see fuel prices or price volatility as a risk to them because 100 percent of the risk is held by captive customers.

Fuel cost sharing is a policy state utility commissions could implement to help fix this problem by requiring utility companies (or more specifically, their investors) to bear just a small portion of the costs. There are a lot of ways a state could go about implementing this. The most straightforward way is to make utilities cover a portion of fuel costs, say 2 or 3 percent.

While customers still pay the bulk of the cost, the company suddenly finds that it is on the hook for some of the costs. This would create an outsized incentive for the utility to negotiate lower fuel-cost contracts, to increase power plant efficiency, to promote efficiency at customer sites, and to invest in resources with low or zero fuel costs like wind and solar.

For a utility with a 3 percent sharing arrangement and a monthly fuel cost of $10 million, the result is that customers pay an overwhelming $9.7 million, but the company must shoulder at least $300,000. Even that small amount could be an incentive for the utility to change its behavior.

$2 Billion in Savings — Maybe More

Let’s put these numbers in a larger perspective.

During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, between 2020 and 2021, vertically integrated utility companies spent $70 billion in fuel costs. These are the utilities that serve 72 percent of US households and they are also the entities largely responsible for building power plants in the first place. For decades, they’ve relied on fossil fuels like coal and gas, and directly passed through those costs to customers.

This reliance on fossil fuels makes the customers served by these utilities very susceptible to fuel price volatility – but on the flip side, the ability to build solar and wind gives utilities the power to avoid these risks in the first place.

But Back to That $70 billion…

Imagine if utility companies were required to pay just a fraction of those costs, instead of passing them on to you and me. Let’s say, once again, a minor 3 percent.

Three percent of $70 billion is $2 billion, or roughly $1 billion per year.

That’s $1 billion dollars per year in savings for retail customers across the country. Savings that are desperately needed given the turmoil of a pandemic, recession, and rapid inflation; savings on utility bills at a time when 20 percent of Americans couldn’t pay their energy bills.

Customers probably would have seen even more savings had fuel cost-sharing policies been in place prior to the pandemic. Fuel cost sharing would accomplish this in several ways. For one, it would create a very strong incentive for the utility company to negotiate the lowest possible price when purchasing fuel. Two, it would force utilities to think twice about investing in potentially expensive gas-fired power plants. Instead, utilities would have an incentive to invest in low- or no-fuel technologies like efficiency, wind, and solar, and would be less reliant on fuels in general. And customers save 100 percent of the costs for fuels that utilities don’t burn.

High Costs and Price Spikes

Fossil fuels like gas and coal aren’t just expensive, they are volatile. This is particularly acute today as both coal and gas spot-prices have risen dramatically. Gas, for example, has risen 600 percent since the start of the pandemic.

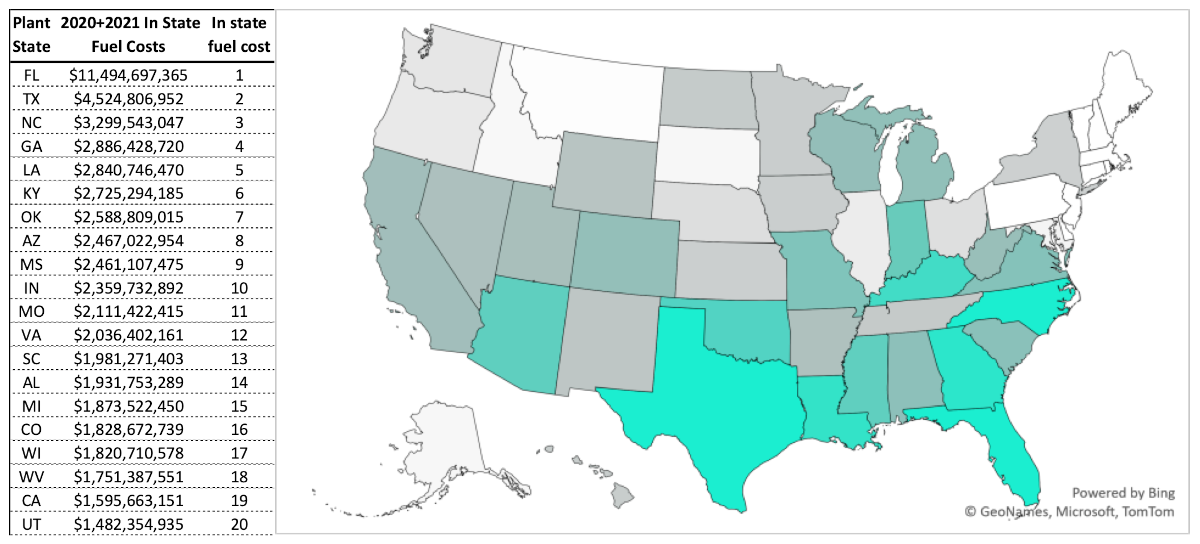

But those costs aren’t felt evenly across all 50 states.

The costs are being felt disproportionately in states that are over-reliant on fossil fuels. Customers in Southeastern states like Mississippi, Georgia, North Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida, which have long been called out for their increasing reliance on gas-fired power plants, are now getting burnt by high prices. But it isn’t just limited to the Southeast. States like Wisconsin, Michigan, and Indiana in the Great Lakes region, along with Colorado, Arizona, and California in the west are all now feeling the burn.

Note: Data only reflects power plants owned by vertically integrated utilities. Restructured states like Illinois, Pennsylvania, and the New England states no longer have vertically integrated utilities and power plant owners are not required to report fuel cost data to EIA.

How Is This Still a Thing?

Fuel pass-through mechanisms came into vogue nearly 50 years ago at a time of volatile prices in the oil and gas industry.

Just like today.

However, one big difference between then and now is that technologies like wind and solar are now a lot more cost-effective. And new technologies like storage and demand response are readily available. These options may require high up-front investment but are more cost-effective over the long run and immune to price volatility.

One might reasonably argue that if utilities are going to bear this “new” risk, it should be offset by an increased rate of return. But that is only one side of the argument. On the other side is mounting evidence that current rates of return are already too high. Moreover, fuel prices and price volatility are risks that the utilities are in the best position to manage, not customers.

To alleviate the pain caused by high cost and volatile fuel prices, we must invest in alternatives. But under the current system, most utility shareholders don’t feel the pain the rest of us are enduring. The best thing utility commissions could do in this moment is to help make sure some of the risk is shifted to those most in power to invest in solutions. Afterall, we’re all in this together.