By the Numbers: Low-Income Energy Assistance

In the United States, low-income families spend a larger percentage of their annual income — three times more on average — on energy costs than non-low income families. Every year, the federal government allocates money to states through the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) to help families in need with their energy bills and efficiency upgrades. This program provides essential relief to millions of families across the country, saving lives and providing huge benefits, but it can be challenging to understand exactly how many families need and receive help.

RMI analyzed a trove of historical data to see how the federal funds are spent, the impact on low-income households, and how this has changed over time. We found that the states are grossly underfunded and that funding would need to increase 10 to 20 times above 2021 levels in order to cover the energy costs of all eligible low-income families.

LIHEAP by the Numbers

Number of Eligible Families

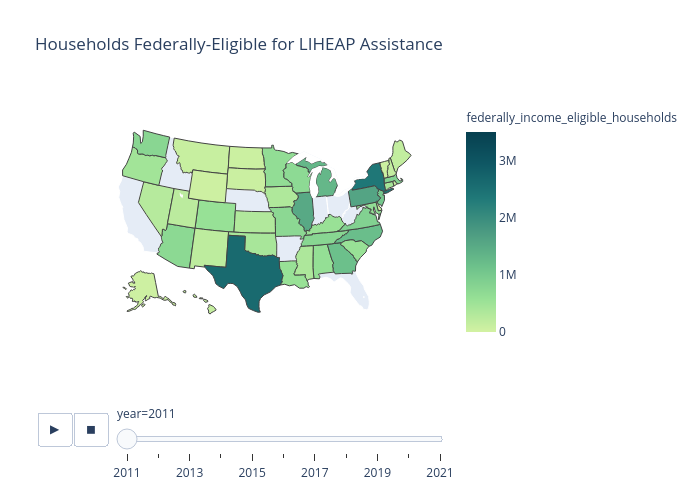

The US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) sets guidelines for LIHEAP funding, but those guidelines can be modified by states. Federal guidance recommends that LIHEAP funding go to those families with an income that does not exceed 150 percent of the federal poverty level, but Iowa, for example, uses a threshold of 200 percent of the federal poverty level. Exhibit 1 shows the number of eligible families by state over time:

It isn’t too surprising that some of the most populous states have the highest numbers of eligible families.

Number of Unserved Families

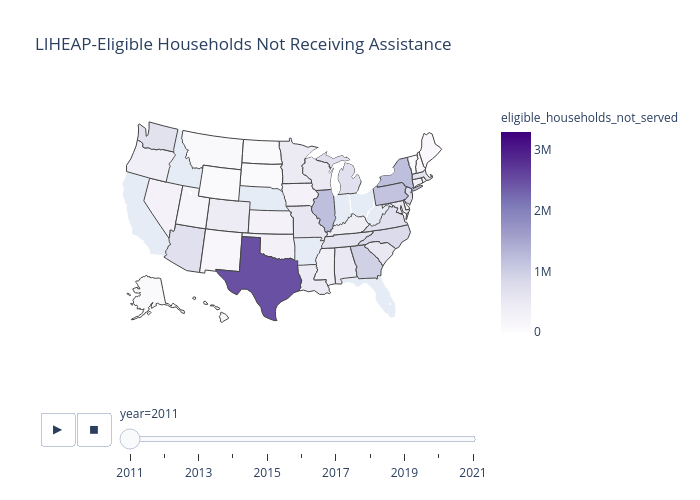

In all states, there are significant numbers of families that are eligible for LIHEAP support but aren’t accessing the funds. Possible reasons include lack of awareness, language barriers, confusion about eligibility rules, and application procedures. An HHS study found that many individuals eligible for federal assistance believe they are ineligible due to their employment or immigration status or have tangible fears they will have to “pay the money back.” Exhibit 2 shows the number of unserved families by state. Use the slide to see how the numbers have changed over time.

California and Texas have the most LIHEAP eligible families that receive no assistance, with 3.27 million and 2.44 million families unserved in 2021.

Percentage of Eligible Families Served

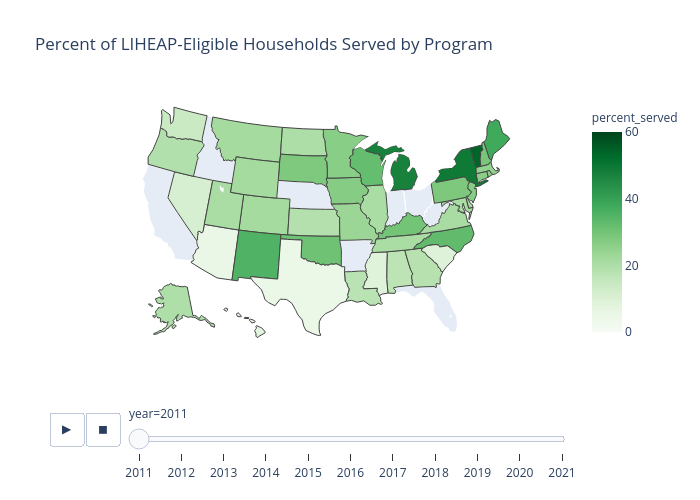

Though California and Texas have the most unserved families, they are also the most populous states. Another way to look at the numbers is the percentage of eligible families served. Exhibit 3 shows the percentage of eligible families served, by state:

Even after accounting for population, California and Texas struggle to serve low-income families. Meanwhile, another populous state, New York, remains consistently one of the best performing states.

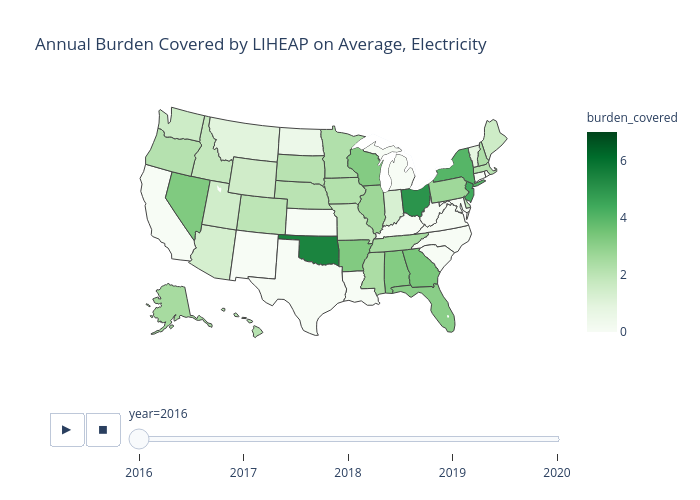

Percentage of Energy Costs Served

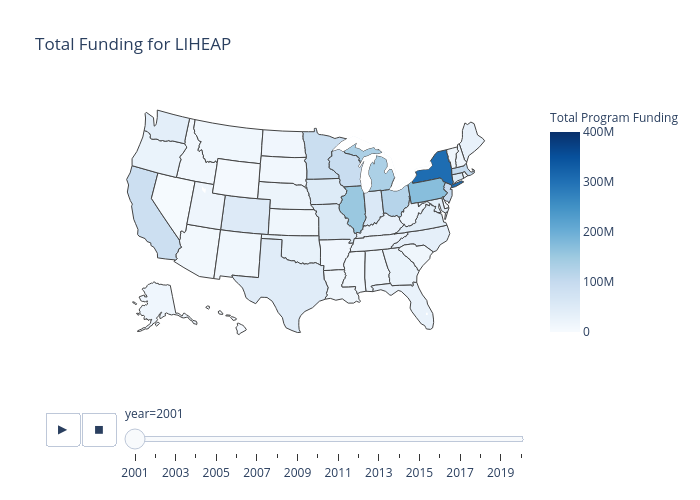

While the charts above show the need to improve education and outreach to qualifying households, the federal government doesn’t provide enough funds to help all the families in need. Exhibit 4a shows the total amount of funding each state has received in the past two decades and Exhibit 4b shows the amount of the low-income family energy costs that funding covers for LIHEAP eligible families.

Solutions

Federal

Thanks to the passage of new laws, including the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and Inflation Reduction Act, several programs designed to address energy poverty will receive an infusion of funds:

- $3.5 billion for the Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP)

- $550 million for the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Block Program

- $3.16 billion for residential energy retrofitting

- $100 million to help families pay their outstanding heating and cooling bills

- 30 percent residential energy efficiency tax credit

- High Efficiency Electric Home Rebate Program, with specific rebates for low-income households

- $837.5 million for energy efficiency, water efficiency, or climate resilience of affordable housing units

- 50 percent Investment Tax Credit for community solar/wind in a low-income building or economic benefit project

While these new funds are critical, much more must be done at the federal and state level to make homes more efficient, shield residents from volatile natural gas prices, and end energy poverty in the United States.

State and local

At the state level, gas and electric utilities need to work with customers and commissioners to ensure eligible customers are getting access to the resources they are eligible for and need. This includes LIHEAP and WAP, along with other provisions like on-bill financing or incentives that make it easier for customers to invest in energy efficiency and rooftop solar.

Effectively using the data utilities and governments may already have can help target vulnerable and burdened households. Yet we must also advocate for more robust data reporting. Utilities can use mechanisms such as segmentation of customer data to gain insight on the real behavior and demographics of their customers.

Nearly all state and local governments have existing programs that support the maintenance of low-cost housing. Investing in clean energy and energy efficiency at those dwellings will decrease costs in the long run while simultaneously improving the quality of life within those homes and providing significant health and climate benefits. Local governments should work to increase and enhance funds available to low-income households for beneficial electrification efforts and make the most of federal dollars that do come their way.

Center the Community

That said, no policy is ever going to solve the underlining energy justice issues that perpetuate energy unaffordability in low-wealth and marginalized communities. The only successful path will be one that is paved intentionally and that seeks out comprehensive solutions to directly confront these problems. These solutions should be coupled with inclusive, proactive efforts that empower families to navigate energy assistance options and receive the help they need. As RMI has said before, state and local governments must “explicitly create resources and frameworks that center community-based and community-rooted organizations as partners in policymaking.”