Seattle downtown and Space Needle view, Washington, USA

Washington Can’t Wait to Electrify

In the midst of 2020 election limbo, the Washington State Department of Commerce quietly released a draft of its Washington State 2021 Energy Strategy. And it’s clear that Washington is not on track to reach its 2030 commitment target or its deeper decarbonization emissions target of being carbon neutral by 2050 unless buildings are rapidly electrified.

The report indicates that economy-wide decarbonization “with the least societal costs” would require a “95% reduction in building sector emissions” by 2050 and “the energy code [being] accelerated to become zero energy, zero-carbon and all-electric no later than the 2027 code.” While Washington is right about the importance of amending building codes to meet climate goals, the code should not wait until 2027 to go all-electric.

Waiting until 2027 to require all-electric buildings would make it difficult for Washington to achieve its 2030 emissions targets and make a 95% reduction by 2050 even more difficult. According to the State 2021 Energy Strategy, it typically takes five to seven years from when a code passes to when it fully applies to all buildings coming into operation. Therefore, waiting until 2027 to require all electric would mean that buildings with fossil fuel fired equipment would be built in the mid-2030s.

As RMI has previously reported in California, waiting another code cycle to electrify buildings can come at great cost and additional years of dangerously high emissions, impacting our health and climate. If Washington manages to amend its code by 2021 to require all-electric buildings, then almost all buildings built in 2030 will be all-electric and will help the state achieve its ambitious 2030 emissions target.

The State 2021 Energy Strategy report names a few other promising policy changes that could make a big difference in the state’s ability to meet its own targets. Among them is the recommendation that the state should empower local governments to require more efficient and electrified new residential structures than is required by the state energy code.

The current policy inhibits local governments from passing electrification ordinances for new residential construction through energy codes. This is a critical barrier to electrification, since local “reach codes” have been a popular and effective method for achieving electrification in other states. This includes 39 cities that are leading the way in California. Even with these setbacks at the state level, local governments are starting to take steps towards building electrification for high-rise multifamily and commercial building types.

Progress in Seattle

Seattle has made some encouraging strides in its new building code, but it could go further. This year’s update to the Seattle Commercial Energy Code—which has been proposed, but not yet finalized— would require partial electrification by eliminating gas water heating in high-rise multifamily buildings and eliminating gas space heating in both high-rise multifamily buildings and commercial buildings. Although this will significantly reduce fossil fuel consumption in these building types, the code could go further, both in terms of what it requires and what types of buildings these requirements apply to.

While the elimination of fossil fuel-fired water heating equipment in high-rise multifamily buildings and hotels is a step in the right direction, these buildings make up only 40% of the square footage of all buildings above 20,000 sq. ft. Considering that water heating is a significant source of building emissions (19% of the direct emissions from buildings nationally), in order to align with Washington’s climate goals, Seattle should go further and require all commercial buildings to shift to electric water heating during this code update.

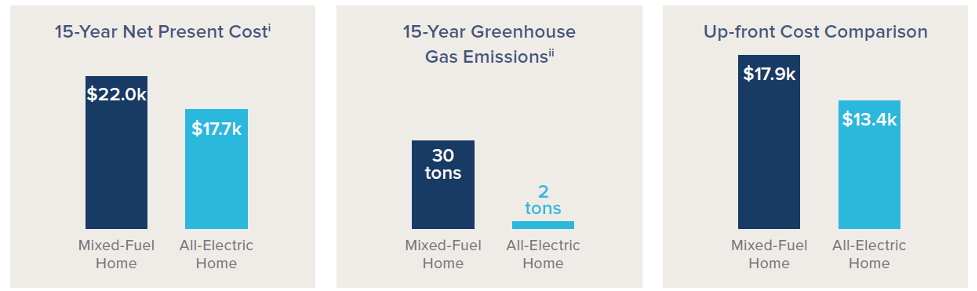

The proposed code also does not require all electric equipment in kitchens, clothes dryers, and fireplaces, which play an important role in making all-electric buildings affordable. As RMI documented in the New Economics of Electrifying Buildings, all-electric homes in Seattle cost $4,500 less than a mixed-fuel home, mostly due to the avoidance of an estimated $2,100 to bring a gas connection to the building.

If Seattle shies away from requiring full electrification, builders and homeowners are not guaranteed to see the system savings from eliminating gas infrastructure. It could also put occupants of those homes at risk of paying extremely high natural gas prices in the future, once other cities in the region decide to electrify. This could further cause those who still rely on natural gas to be saddled with the increasing burden of the maintenance and operations costs of the aging natural gas system. In order to get ahead of this, cities like Seattle should move quickly to an all-electric code, leaving behind partial electrification as quickly as possible.

All-Electric on the Horizon

While Seattle may miss the early opportunity to take advantage of full building electrification, Thurston County and the City of Bellingham are taking steps towards it. In a draft of its Climate Mitigation Plan released this year, Thurston County recommended that the city “ban new natural gas connections in new buildings.” This could be the signal that local organizers need to complete work with the County to pass an electrification ordinance.

Meanwhile, earlier this year, the City of Bellingham discussed a groundbreaking policy to ban natural gas in space heating for existing buildings by 2040, a first in the country. Although that effort may have stalled, on-the-ground organizers have reported that the city council plans to move forward with an ordinance to ban natural gas in new construction in the next few months.

With the upcoming 2021 legislative cycle beginning in the next few months, the State of Washington has a powerful opportunity to remove regulatory barriers that prevent local governments from exceeding the statewide energy code. This would be a small but crucial change that would allow cities that are ready to electrify to include residential homes in their local reach codes. Then, Washington must turn its attention to amending building codes to require new buildings be all-electric by 2021.

Washington has set ambitious but necessary climate targets. The decisions it makes in the next few years will determine whether or not it is able to reach them.