Protecting and Empowering Communities during Disasters

Local Texas governments can show the way through the use of community resilience hubs

Over the past few years, Texans have come to understand the need for resilience in the face of a changing climate. Hurricane Harvey in 2018, Tropical Storm Imelda in 2019, and Hurricane Laura last summer each brought a so-called 500-year flood to the Texas Gulf. February’s devastating winter storm left 4.5 million Texans without power and water for over 48 hours and caused $295 billion in property damage and the direct deaths of 151 people.

Centers for Disease Control data indicates the true death toll is four or five times the official count. The majority of fatalities occurred among the most vulnerable populations, such as the elderly, chronically ill, people dependent on medical equipment, and those without adequate shelter.

This traumatic event, as well as the less newsworthy but far more frequent climate disruptions like flash floods or heat waves that cause Texas’ grid operator to request residential conservation, put a spotlight on the inequities we know to be embedded in our cities. Marginalized communities are more likely to live in neighborhoods that experience hotter temperatures, poorer air quality, and industrial pollution, while also being the most vulnerable during a climate disaster. Disadvantaged households are less likely to have access to a private vehicle or emergency savings, making it that much harder to stock up on groceries in advance of a storm or pay for necessary repairs during and after.

Community resilience hubs (CRHs) offer local governments a powerful means of supporting vulnerable populations before, during, and following an extreme weather event or other disasters, while simultaneously empowering and shifting resources directly to those communities.

Providing Renewably Powered Emergency Services and Shelter through CRHs

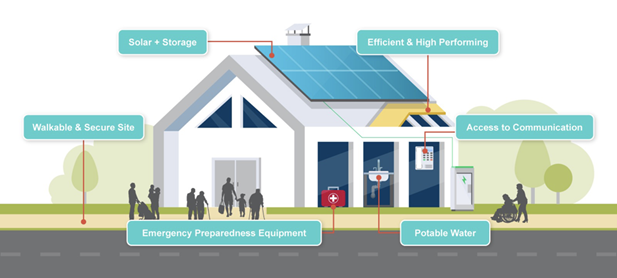

CRHs can help communities better prepare for grid failures in extreme weather and other disruptions to essential urban systems. They are physical sites where residents can access crucial services during a large-scale emergency like flooding, wildfires, cold snaps, and heat waves.

CRHs must provide efficient shelter and reliable backup power (solar plus storage). They must also be supported by community services that can provide food and water, ideally within walkable, dense urban environments. It is also essential to place CRHs within low-income neighborhoods, as these areas are more likely to lose electricity than wealthier ones located within critical grid circuits due to their proximity to hospitals, fire stations, or other emergency facilities.

Lengthy blackouts pose a massive risk to human health. This is particularly true for populations dependent on medical equipment, and for all residents during extreme heat and cold. Moreover, reliable sources of electricity are critical to ensure that communications with and between first responders can be maintained throughout an emergency.

CRHs require on-site energy generation to keep things running through a utility outage. Technologies like PV panels coupled with battery storage allow CRHs to power life-saving medical equipment, keep food and medications refrigerated, maintain critical communications (from first responders’ equipment to residents’ cell phones), and regulate temperatures to offer a safe, livable environment.

Such power can be provided by fossil fuel generators, but these systems can be limited by the availability of fuel, and they also pollute the local air and remain idle the vast majority of the year. In contrast, systems designed around solar PV and battery storage can operate year-round, providing reliability while also reducing the CRH’s energy costs. Alternatively, hybrid systems combining both fossil generators and solar plus storage have been shown, in some cases, to be more cost effective than fossil fuel generators alone.

Empowering Local Organizations to Create and Operate CRHs

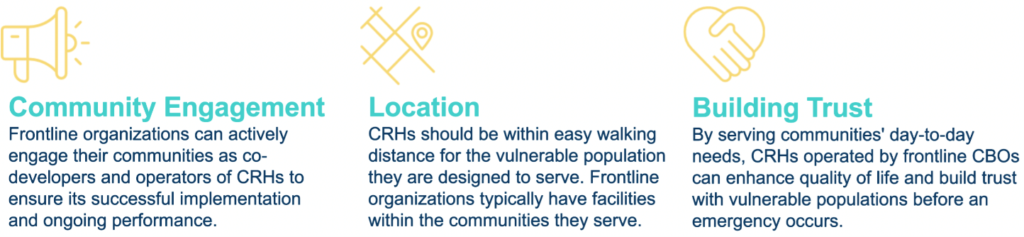

While local governments can create CRHs at their own facilities, such as schools, convention centers, affordable housing complexes, and community centers, they can also offer support to local nonprofits or other private entities to expand the network of CRHs across the region.

Frontline, community-based organizations (CBOs) can be a natural fit to own and operate CRHs, as they are trusted voices within their communities. On a day-to-day basis, CBOs offer programs that improve residents’ health and well-being, and they build strong relationships with local residents that can be drawn on during an emergency. In addition, facilities owned by frontline community-based organizations already serve as local gathering, learning, and collaboration spaces, and as such are particularly well-suited to mobilize and assist residents during a crisis.

There are a variety of ways in which local governments can help frontline CBOs establish CRHs. Some municipalities earmark dollars in their annual budgets to directly support CBO-owned CRHs. Others provide staff time from a variety of departments, such as the sustainability, equity, or public health offices.

These city officials support CBOs–many of which are staffed by volunteers–in writing grant applications or finding other funding sources, as well as accessing technical expertise. The city officials also maintain regular communication in order to better understand residents’ needs and build trust in government. Local government staff can also help CBOs communicate with one another and share knowledge, supplies, and other resources.

To learn more, consider visiting USDN’s Resilience Hubs portal, which offers guidance documents, analytical tools, and other resources. Relevant case studies include the Baltimore City Community Resiliency Hub Program, Minneapolis’s Climate and Health Resilience Hub Pilot Project, and Austin’s recent Council resolution to launch its first six hubs.

Case Study: Millvale, Pennsylvania

A CRH developed in the town of Millvale, a small Pittsburgh suburb, provides a useful illustration of how local governments and community-based organizations can work together to enhance resilience while addressing underserved community needs. After several climate-exacerbated flooding events, Millvale began considering the development of the area’s first CRH equipped with solar plus storage. Key stakeholders, including municipal officials, the community development corporation, the town library, and a local nonprofit, wanted the “energy hub” to also mitigate the neighborhood’s food insecurity and underemployment challenges.

Several key initial steps included finding a location, identifying the primary operator, and designing the system. A vacant social hall, which was centrally located and above the floodplain, was singled out as the optimal site for the hub. Meanwhile, a local nonprofit partner, New Sun Rising (NSR), was identified as the best backbone organization to lead the CRH initiative.

By placing the initiative within a nonprofit as opposed to being municipality-driven, the project opened itself up to multiple external funding streams without placing a burden on overstretched municipal staff. Then, the key stakeholders established an important partnership with the Energy GRID Institute at the University of Pittsburgh to conduct a feasibility study and determine the viability of renewable energy generation plus battery storage in the space. As a result, a 26 kW solar array with a 30 kWh smart battery storage system was selected for the site.

To support the community vision and financial viability of the project, organizers recruited additional tenants for the building from like-minded, mission-oriented nonprofits, as well as a for-profit startup catering business. Community-based stakeholders and tenant partners worked together to develop a programming vision that included food access and education as well as renewable energy workforce development.

By securing tenant commitments and conducting a feasibility study, NSR was able to develop a comprehensive project budget, supported by projected revenues, that made it a strong candidate for philanthropic and government grants. These revenues include tenant lease payments, event rentals, and renewable energy sold back into the grid. The project was ultimately funded by multiple sources, including debt leveraged by demonstrating sustainable revenue sources.

True to its mission, the hub played a critical role during the COVID-19 pandemic. The area was already a food desert, and once the pandemic struck, food insecurity became an even more pressing issue. In partnership with the USDA’s Farm to Families program, the hub distributed nearly three tons of fresh produce each week to families in Millvale. Today, as things cautiously open back up, the Millvale Food + Energy Hub is a busy café and a community space. It is also home to four nonprofit organizations and a renewable energy training center.

By remaining flexible and being open to learning along the way, Millvale was able to tackle the challenges that come with innovation and accomplish several long-standing community goals while also creating a vibrant space for all.

Building Resilient Texas Communities

As the climate crisis worsens, vulnerable populations in Texas and beyond will increasingly be at risk from extreme weather and frequent disruptions to local government systems. CRH facilities offer a compelling mechanism through which local governments can provide critical shelter and services to the most vulnerable, promote local renewable resources, and address other critical community needs. As such, it is vital that local governments developing CRH initiatives or individual facilities work in close partnership with local organizations like frontline CBOs.

To directly support local governments in this work, RMI is launching a Community Resilience Hub initiative in September to provide technical assistance to local governments in Texas seeking to deploy CRHs. If you are part of a local government or frontline organization in Texas focused on community resilience and are interested in learning more about the Resilient Texas Communities program, please contact Heather House.

Acknowledgments: We thank Steve Abbott, Heather House, and Resilient Texas Communities program colleagues for their contributions to this article.